Women in South Korea do not choose to get married and sleep. With the lowest fertility rate in the world, and the members of the country do not change anything, since it begins to decrease.

"I've never had plans for children," said Jang Yun-hwa, 24, as he spoke at a weekend coffee shop in Seoul during a weekend in Push.

"I do not care about the physical pain of a woman, the first point of my life."

"Instead of being part of the family, the defense wanted to live alone and live according to my dreams," he says.

Yun-hwa na Korea applies to the figure of the bride, who not only sees life, and many families.

There are women who have been pregnant without the laws of the people, or giving their chances, except age, but in practice, that is, that is not it

The story of Choi, Jeong Moon, who lives in the west and around Seoul, is a powerful problem of the human body. The person who was pregnant with his wife and many said that the culture will be overwhelmed.

"My boss said," When you have a small baby with a preference for you and the other company, you can keep working, "said Moon Jeong.

"I always gave this problem."

The books now have Jeong taxes. Returning, as the season progressed, the commander gave him more and more, and when he filed a complaint, he said he had no devotion. Finally, the tension reached the point of crisis.

"I'm crying". I was sitting in a chair and all my stress began to feel that the body could not open my eyes, "said Jeong Moon because of his opening, he has a skin disease that he has developed against persecution.

"The air of my house, by parasites and removed".

In the hospital, the doctors said signs of stress and behavior.

When Moon-jeong returned after a week in the hospital, she saved her pregnancy, felt that her boss was doing everything she could to take off her job.

She says that this type of experience is not unusual.

"I think there are many cases in which women are pregnant when they are pregnant and you have to think seriously before announcing your pregnancy," she says.

"Many people do not have children around me and it is predicted that they would not have children".

When Moon-jeong returned to work after a week in hospital, her pregnancy saved, she felt her boss was doing everything he could to force her out of her job.

She says this kind of experience isn't uncommon.

"I think there are many cases where women get concerned when they're pregnant and you have to think very hard before announcing your pregnancy," she says.

"Many people around me have no children and plan to have no children."

It is often believed that it is a culture of effort, a long time and a commitment to work for a significant change of South Korea over the last 50 years, from one developing country to one of the largest economies in the world.

But Yun-hwa said that women's role is often forgiven for this change.

"The success of Korea's economy has been a success in factory workers with small women," he said.

"And they also provide care services so that family women leave and focus on the task."

Now women have become more employed in past people: in administration and in between professions. Despite the rapid social and economic change, the attitude of slow sexual change.

"In this country, women are expected to be cheerleaders for children," says Yun-hwa.

More than that, he says, there is a tendency for married women to take care of their family members.

"There are many possibilities where even a woman has a job, when she, her children and children, part of the care of children, is almost entirely their responsibility," she said. "And he also asked if he would take care of his in-laws if they were sick."

The average person in South Korea spends 45 minutes per day on unpaid work, such as childcare, according to OECD figures, while women spend five times.

"My personality does not apply to this type of support," says Yun-hwa. "I'm busy with my own life."

However, not only does he not care about marriage. He does not want friends. One of the reasons for this is the risk of becoming a victim of retaliation and claims that it is a "big problem" in Korea. But he is also worried about domestic violence.

The Korean Institute of Criminology published last year the results of a study in which 80% of the men evaluated were convicted of abusing their partners.

When I asked Yun-hwa how they saw women in South Korea, she replied in one word: "Slave."

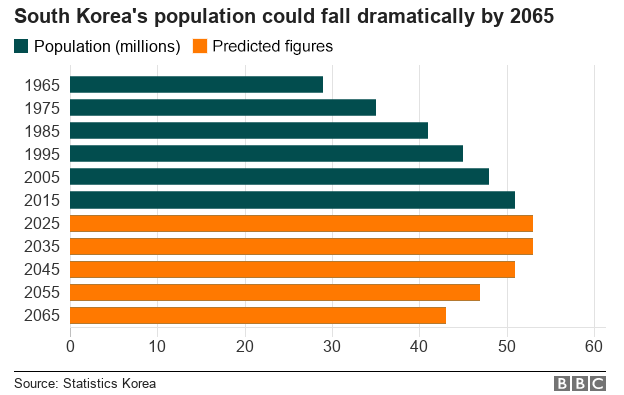

It is clear that it is fueling the shortage of children in South Korea. In South Korea, marriage rates are the lowest since the beginning of the study, with 5.5 per 1,000 inhabitants, compared to 9.2 in 1970, and very few children were born in marriage.

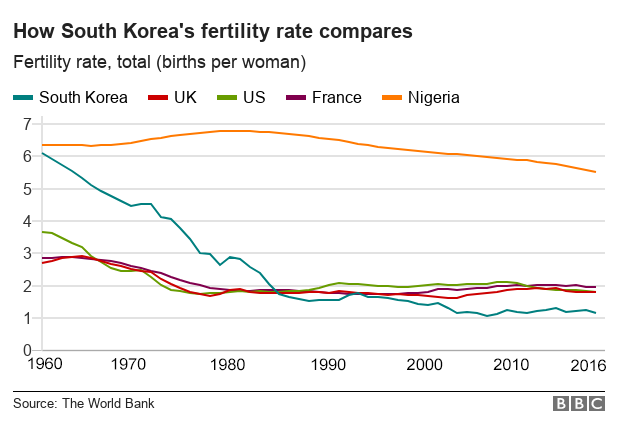

Only Singapore, Hong Kong and Moldova have fertility rates (number of children per woman) lower than South Korea. According to figures from the World Bank, everything is at 1.2, while the replacement rate, the number needed to maintain a population at the same level, is 2.1.

Another factor that people put into a family are the costs. While public education is free, the competitive nature of the research implies that parents must pay additional tuition fees for their child to follow them.

All the components combine to create a new social phenomenon in South Korea: the Sampo generation. The word "shampoo" means giving three things: relationships, marriages and children.

Absolutely free, Yun-hwa said he did not give these three things: he was chosen not to follow them. He does not say if he wants to be single or seeks a relationship with women.

Talk to South Koreans of previous generations about the low fertility rate and the difference in posture is chronic. They see people like Yun-hwa very individualistic and selfish.

I started chatting with two 60-year-old girls who enjoy the park through the creek that runs through downtown Seoul. I have been told that he has three daughters for 40 years, but he has no children.

"I try to establish patriotism and duty in the country with children and, of course, I want to see them online," he said. "But his decision is not."

"There should be a duty in the country," added his friend. "We are concerned about the low fertility rate here."

Yun-hwa and his contemporaries, the children of a globalized world, are not convinced of these arguments.

When I told him that if he and his companions had no children, that the culture of his country would be dead, he told me that the time had come for the culture led by men to leave.

"He must die," he said and broke out in English. "Must die!"