When Biplav Bhatta touched down at Queen Alia International Airport in Jordan in July 2004, he was genuinely excited at the prospect of working as a cook – a lucrative job with a high salary for a common Nepali migrant worker. His luggage in one hand, he held an envelope in the other, which he was instructed to give to people who would come to receive him and 31 other fellow countrymen.

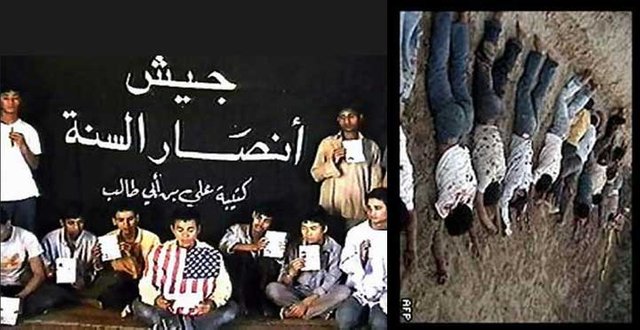

Then just 22, Bhatta, who is among the few who narrowly survived the killing of 12 Nepalis in Iraq later that year by the Ansar al-Sunnah extremist group, though he was in safe hands when a man came to the group and took similar envelopes from them. The man introduced himself as a friend of Pralhad Giri, operator of the Kathmandu-based Moonlight Manpower Company that had arranged their visas and jobs.

Afterwards, two agents – Khalid and Jamim – seized the passports of all the Nepali youths one by one- and asked them to board a bus to go to their ‘workplace’. The youths assumed the two Arabs were their employers and followed the instructions. It was the beginning of a long and arduous journey to a fate unknown.

The agents drove for hours and stopped after reaching a strange and remote place where there were only a couple of abandoned houses. The houses were very old and partially damaged, with broken doors. There was no toilet and no place to sleep.

When the group arrived, other Nepali migrant workers mostly from the Terai had already been stranded there since the previous three days.

The migrants were famished and had fallen ill. One of them, Ramesh Khadka, had a high fever. Bhatta gave him a paracetamol that he had brought from Nepal as suggested by his elder brother. He put a cold towel on Ramesh’s forehead. This helped him feel better. But overall, the situation was worsening.

The Arab agents used to appear after gaps of a few days. A woman who introduced herself as the wife of one agent used to throw the migrants a sort of bread and some water in jerrycans from upstairs. Only uncooked rice and battered pots were provided. They used an abandoned wrench as a ladle. For days, they slept under the open sky braving the extreme heat.

“The horrible situation made us realize that we had totally missed out on our destination. We feared further trouble,” said Bhatta, sharing his story from a restaurant that he currently runs in Lalitpur.

The Arabs later turned out to be trafficking agents supplying unskilled workers to war-torn Iraq at a time when the US invasion there was at its climax.

The migrant workers finally started asking, “When are you sending us to work?” The agents initially shunned the question but later replied in two words, “keep quiet”. They even threatened to finish them off if they asked again.

Even though all the captive migrant workers were from Nepal, they got to know each other only after landing at the Jordanian airport. Bhatta had shared the bare ground at night with fellow travellers Ramesh, Dil Bahadur and Jeet Bahadur Thapa.

A local of Masel in Gorkha, where he could find no work, Bhatta had paid Rs 125,000 to the owner of Moonlight Company for a job in Jordan as an assistant cook. He had no other option as his wife was three months pregnant and the family needed money to get by.

Similar family situations back home also helped the youths become closer to one another. Close friendships develop quickly when aboard.

Life in Jordan was scary. The environment was not suitable even for cattle. Fed up with the inhuman treatment, the youths demanded either to be allowed to return to Nepal or given work immediately.

Under pressure from the workers, the agents arranged interviews for them after three days without food and water. But only 12 migrant workers were selected in the first lot.

Two days after the interview, the agents reached there at 10 pm with a vehicle. Those selected felt huge respite on leaving a place like ‘hell’ although it was not certain where they were heading.

Other workers including Dil Bahadur, Mangal Limbu and Ramesh were left waiting desperately for their interviews. Unfortunately, Ramesh, Dil Bahadur and Jeet were among the 12 Nepalis slain in Iraq.

The first lot including Bhatta had already crossed the Jordan border and they survived. “I think luck favoured me. I could also have died if I was with those left behind,” he said.

During the 12-hour drive at night, nobody except the driver was awareof where they were going. An armed group stopped them on their way to Iraq and the driver gave them a huge sack. Bhatta believes they were crossing the Jordan border into Iraq illegally and the sack contained bribe money.

They reached Iraq next day. They were dropped inside a house with a heavy compound where US marines were on strict guard. One man, who was wearing a brown dress with DNP written on the hat, took them to the US marine base and asked Bhatta to clean up the garbage. His friend Abdul was selected to work as a butcher was asked to clean the trays.

Before departing for Jordan, they were told that each worker would get $650 month but the employer in Iraq informed them they would get just $300 and $50 would be deducted from their monthly salary.

Since he was promised the position of assistant cook by the Nepali manpower agency, Bhatta was hesitant to work as a cleaner, that too at a low salary. But they were completely at the employer’s mercy.

Bhatta (center) working as cook at a restaurant in Thamel in 1998.

Dismayed with the nature of the job and the security situation, they protested, saying they wouldn’t do any job other than what they were promised. Managers tried to convince them that ‘more friends’ were also coming.

Three or four days after Bhatta’s team reached Iraq, the managers said yet another vehicle was being sent to Jordan to pick up the remaining Nepali workers.

The vehicle, however, returned empty. Tension ran high among them about the migrant workers who were stuck in Jordan. They made inquiries, but in vain.

Around a month later Bhatta’s group learnt from international media outlets including CNN and BBC that 12 Nepalis were abducted and killed in Iraq. There was a curfew in Nepal after the Iraq killings.

The news agitated them. They guessed that their friends were also killed but could not get any details about the deceased until they returned home. It was not possible to return home from war-torn Iraq then.

Dismayed by the shocking news and frequent mortar attacks around their settlement, the Nepali workers demanded to return to their home country. In response, the managers stopped providing food. Their passports had been seized long before, rendering them helpless.

Having no options they were forced to spend their days in bunkers, listening to the sound of frequent mortar attacks.

“Flak jackets were provided while working in the kitchen but they did not allow us to communicate with our families for months,” recalled Bhatta. It took six months for him to get in touch with his family back home.

Having spent 20 months at the US base in Iraq, his manager finally agreed to let Bhatta return to Nepal after finding a substitute. They helped Bhatta reach the airport so that he could manage his way to Jordan and back home.

His deep suspicions regarding those killed in Iraq being his friends were confirmed after he landed in Kathmandu. “It was really disheartening to lose friends,” he said.

As of now, the government has not taken action against the manpower company responsible. Bhatta expressed ire over the government’s inaction.

“It is not just my case. Many Nepalis are cheated and abused during foreign employment. But our government is doing nothing to book the companies trafficking unemployed youths aboard.”

Soon after the abducted 12 migrant workers were killed in Iraq, the government formed a panel headed by retired Supreme Court justice Top Bahadur Singh. The committee submitted its report to then PM Sher Bahadur Deuba, but it was never made public nor was the manpower agency responsible booked.

“At that time, the government suspended the manpower company, which had worked as an agent of a Jordanian company trafficking workers to risky areas,” said Ganesh Gurung, a former member of the National Planning Commission, who keeps tabs on migration affairs.

Over 1,000 Nepalis exit Tribhuwan International Airport every day to work in foreign lands. Majority of those who have returned have experiences and tales like Bhatta’s: forced to work in an unsafe environment at low pay, and subjected to abuse, threats, rape and other forms of violence. Their stories are almost always grim.

Source: myRepublica

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

https://myrepublica.nagariknetwork.com/news/he-narrowly-escaped-the-2004-iraq-massacre-of-12-nepalis/

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Congratulations @nareshbhatt! You received a personal award!

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

Do not miss the last post from @steemitboard:

Vote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit