Did you know...?

¬ There were more than 5,300 plans and drawings for the

Tower

¬ The Tower was built in 2 years, 2 months and 5 days, from

1887 to 1889. It was an instant financial success.

¬ There were 18,000 components, made by 100 ironworkers

off-site, then assembled by 130 workers on-site.

¬ It measures 410 feet (125 m) on each side and stands

1,024.5 feet (312.27 m), and weighs 9,500 tons

¬ The tower sways only 4.5 inches at the top.

¬ For many years, the Tower was the world’s tallest structure

with a safety elevator designed by Otis

¬ Not one fatality occurred during construction.

¬ Guy de Maupassant, Alexander Dumas, Emile Zola, and

other luminaries signed a petition objecting strenuously to

the Tower

¬ Eiffel also designed the iron framework inside the Statue of

Liberty.

“We, the writers, painters, sculptors, architects and lovers of the

beauty of Paris, do protest with all our vigor and all our indignation, in the

name of French taste and endangered French art and history, against the

useless and monstrous Eiffel Tower.” Clearly, initial reaction to the Tower

was mixed, as evidenced by this quote from a petition presented to the

government of the City of Paris. The petition was signed by—among others—

Guy de Maupasssant, Alexander Dumas, Emile Zola, Charles Gounod, and

Paul Verlaine.

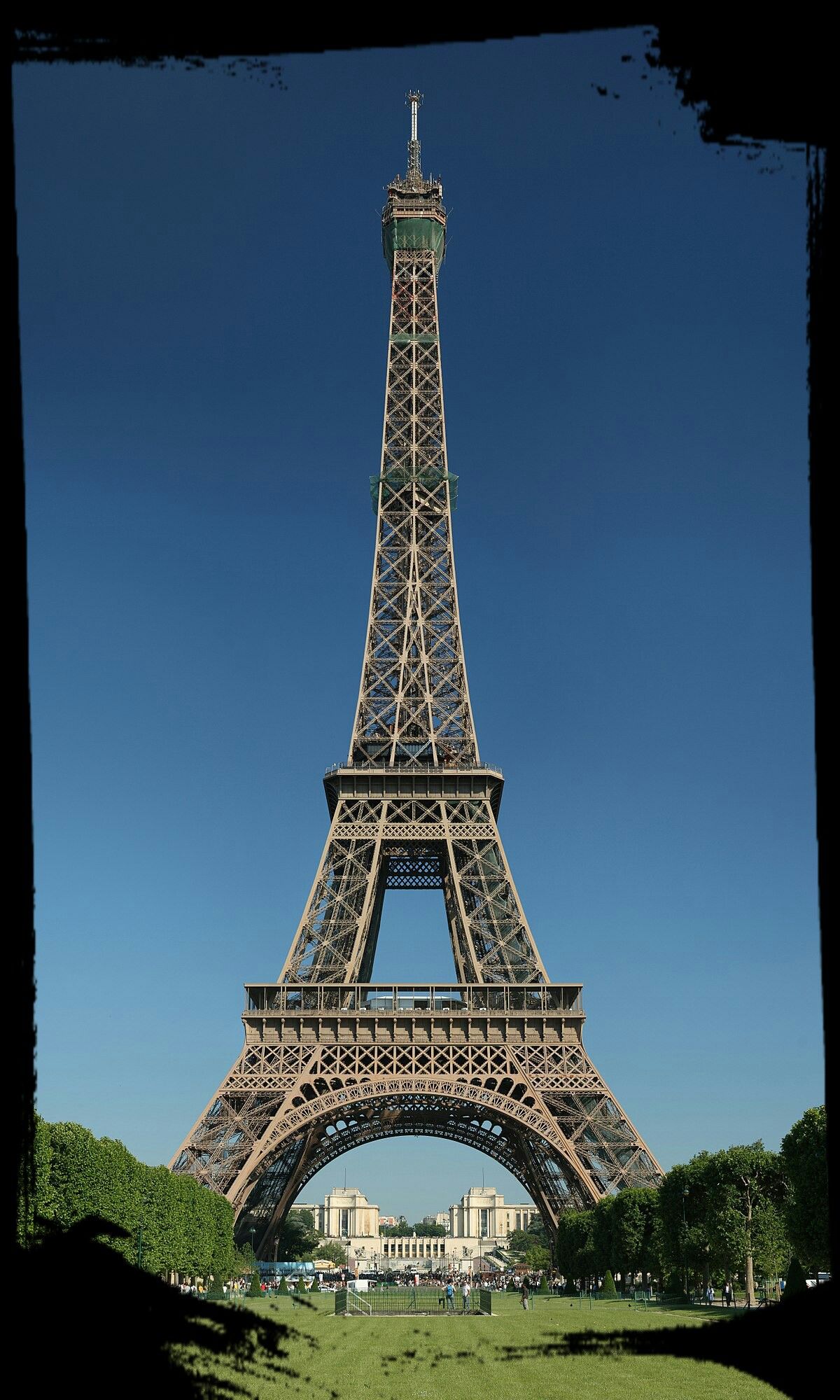

Paris’s soaring, open-lattice, wrought-iron Eiffel Tower, originally

built for the International Exposition of 1889 commemorating the centennial

of the French Revolution, remains a universally recognized symbol of France,

and indeed all Europe. Over 700 proposals had been submitted by architects,

engineers, sculptors, and artists. One was selected unanimously, the design by

Gustave Eiffel.

The tower became an instant icon, the site of many romantic moments,

as well as staggering feats of individual bravado. In 1923, the man who would

become Mayor of the district of Montmartre showed his derring-do by

bicycling down the tower using its legs as a ramp! In 1954, a mountain

climber scaled its height, and in 1984 two English chaps parachuted from the

top.

HISTORY

The plan for the tower was submitted to the design competition by the

civil engineer Gustave Eiffel (1832-1923), already well-known for such works

as the arched Gallery of Machines for the Paris Exhibition of 1867, the dome

for the Nice Observatory, a harbor in Chile, a 541-foot arched bridge in

Garabit, France, a pre-constructed spanned bridge in China, and an iron bridge

at Bordeaux (the construction of which involved the first use of compressed

air to drive piles). Eiffel’s viaduct over the Truyère, which stretched 1,850

feet (564 meters), with a central arch span of 541 feet (165 meters),

constituted an engineering record: with a height of 400 feet (122 meters) over

the river, it was for years the world’s highest bridge.

While Eiffel receives all the credit for the tower, it must be noted that

the original conception for the 1889 exposition tower came from two

engineers at Eiffel’s firm: Maurice Koechlin and Emile Nouguier. It took

years of work by more than fifty engineers and designers to prepare the

approximately 5,300 plans and drawings for the tower.

Reproduced here is the official agreement of January 8, 1887, which

outlines Gustave Eiffel’s construction and operation of the tower. In addition

to Eiffel, it was signed by Commerce and Industry Minister, Edouard

Lockroy, who, as commissioner general of the Exposition, organized the

design competition, and by Eugène Poubelle, prefect of the Seine.

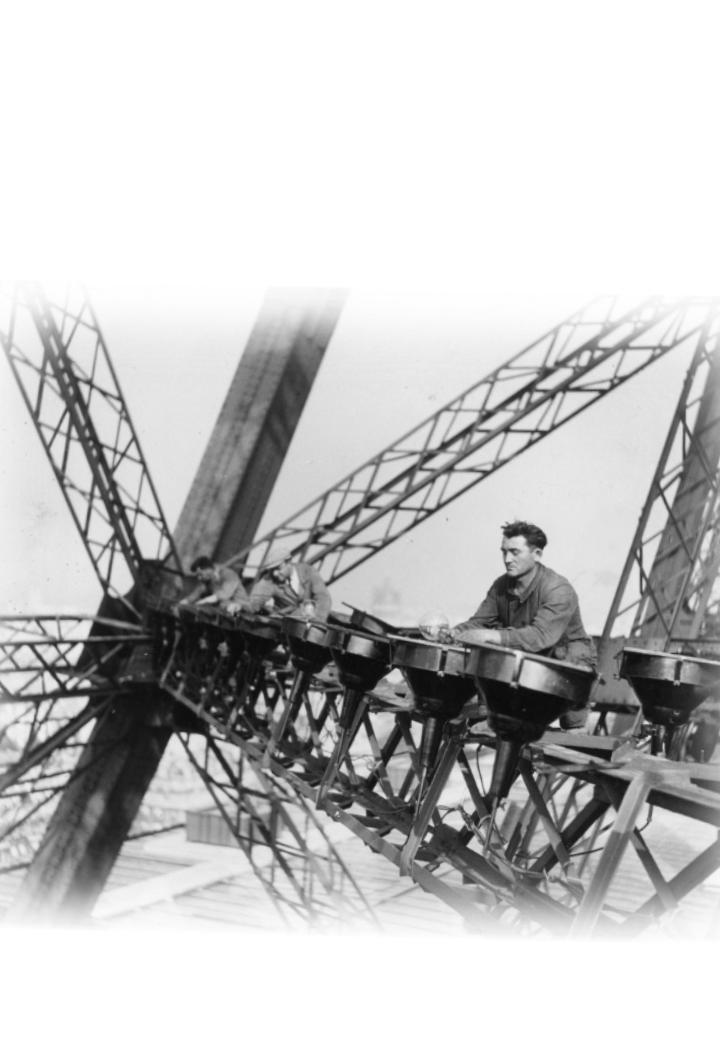

Once approval was given, the project proceeded at a rapid pace.

Excavation commenced on January 26, 1887, and assembly of the metal

structure on July 1. The tower’s 18,000 component parts were made by more

than 100 ironworkers at the workshops of Eiffel’s company in the outskirts of

Paris, and were assembled by more than 130 workers at the exposition site.

The exposition was scheduled to open on May 6, 1889. Contrary to the

expectations of many observers, Eiffel easily fulfilled his commitment to

complete the project on schedule, finishing on March 30, 1889. In a ceremony

the following day, a small group of dignitaries accompanied Eiffel to the top

where he raised a huge French flag with the letters “R. F.” (République

Française), and was awarded the Legion of Honor.

The tower rises from a square base measuring 410 feet (125 meters) on

each side, to a height of 1,024.5 feet (312.27 meters) (even higher today

because of the addition of broadcasting antennas). Until the completion in

1930 of New York City’s Chrysler Building, the Eiffel Tower had been the

tallest man-made structure in the world. Despite its immense height, the tower

weighed approximately 9,500 tons, with the metal framework accounting for

7,300 tons. Because of its cross-braced, latticed structure, wind had little

impact on its stability.

The Eiffel Tower was an immediate success. Construction costs, said

to be approximately 8 million gold francs, were quickly covered by receipts

earned from visitors. By the time the fair closed in early November 1889, two

million people had visited the tower. By the end of that year, receipts totaled

5.9 million gold francs. As of 2002, the total number of visitors to the tower

had exceeded 200 million.

CULTURAL CONTEXT

France is the country that coined the phrase Les Grands Travaux

(Large-scale Engineering Works). In a French encyclopedia, an article on Le

Canal des Deux Mers (The Canal of the Two Seas) states that the Canal was

the greatest public work since the time of the ancient Romans. Thus, Eiffel

was in the authentic tradition of Les Grands Travaux. Perhaps the world’s

greatest artist in the medium of iron, Eiffel also wrote a book entitled

L’Architecture Métalique.

He attended the Ecole Centrale, a school for the arts and

manufacturing. But if his school prepared him for art, he also participated in

its manufacturing mission, as Eiffel continued to design projects using iron—

railway viaducts with supports of iron, and a bridge over the Douro River in

Portugal. He decided to open his own factory just outside Paris in the town of

Levallois-Perret. This combination of artistry, experience with iron, his own

manufacturing and production facilities, and extensive business management

experience enabled Eiffel to be one of the first macro-engineers to complete

his great work not only within the prescribed budget but ahead of the

estimated schedule.

While France was the nexus of great engineering works, it may have

been Eiffel’s experiences in the United States that sparked his the idea for the

tower. In 1876, he saw a proposal by two Americans, Samuel Fessenden

Clarke and Arthur M. Reeves, who had designed a circular iron-framed tower

intended as an engineering monument and icon for the Centennial Exposition

of 1876. Clarke and Reeves’ design was included in the 100th anniversary of

the American Revolution—a fact that may have influenced Eiffel as he

considered a piece for the 100th

anniversary of the French Revolution. Eiffel

himself credited Clarke and Reeves as the source of his inspiration.

Eiffel’s design took advantage of new materials with which architects

and engineers were beginning to become familiar. Before this time, Les

Grands Travaux were large in the sense of wide and long, and often based on

stone construction—canals, aqueducts, bridges; they were not especially high,

except of course for the famous medieval cathedrals. Eiffel’s monument is a

marvel of physics. He was a pioneer in the aerodynamics of high frames,

using a mathematical formula to determine the exact curve of the structure’s

base that would withstand the force of the wind against it and transform that

force into added structural support. It is noteworthy that the Eiffel Tower

sways only 4.5 inches at the top. The exact math of Eiffel’s discoveries can be

found in his 1913 work, The Resistance of the Air. Eiffel’s physics paved the

way for the modern skyscrapers erected in recent years.

The tower’s height is an important factor in its endurance. Although

the contract set twenty years as the length of time the tower would remain in

the Parisian park, the Champs de Mars, when the contract expired, the tower’s

height made it the obvious choice for siting communication antennae. So it

remained in the park—to send telegraph signals.

Eiffel saw the advantages of adding communication antennae to the

tower. When the first radio signals were sent by Eugène Ducretet in 1898, it

was Gustave Eiffel who approached the military in 1901 and suggested that

the tower be incorporated into an infrastructure for long-distance radio

communications. By 1903, radio signaling had made major progress, and the

military was sending messages from the tower to bases around Paris, and by

1904 to the French east coast. A permanent radio station was installed in the

tower in 1906. In 1910, its antenna became part of the International Time

Service. Ever an enthusiast for the modern and new, Eiffel was gratified when

the first European public radio broadcast came from the tower in 1921, just

two years before his death. It would have pleased Eiffel that in 1957 television

signals were added; no doubt he would approve of the web cam that today

allows people from all over the world to see vistas from the Eiffel Tower via

the Internet.

PLANNING

The Eiffel Tower was perhaps more carefully and meticulously

planned than any macro project in history—and all the planning was done by

Eiffel himself. In fact, planning may have taken longer than building. As a

result of such fastidious preparation, the project was finished ahead of

schedule. In just two years, two months, and five days, Eiffel and his team

successfully accomplished this engineering feat with such perfection that the

individual pieces were tooled to an accuracy of one-tenth of a millimeter.

It took tremendous planning to foresee that most of the parts would

have to be forged, machined, and assembled off-site and then installed.

Workers at Eiffel’s factory at Levallois-Perret made the parts; many had

previous experience working on Eiffel’s viaducts.

The on-site work crews required special organization. Teams of four

men were needed to install each rivet: one held the rivet in place, one heated it

red-hot, a third made sure the head of the rivet was positioned exactly right,

the fourth hammered it into place. Eiffel had planned the process with such

precision that the hot rivets could cool right in place, expand as they cooled,

and thereby strengthen the structure by taking advantage of natural

thermodynamic principles.

The Eiffel Tower was one of the most meticulously planned and best-

managed macro construction projects in history.

BUILDING

The tower was constructed of iron and held together by 2.5 million

rivets, all resting on a masonry base. The foundation was made of caissons

filled with concrete and sunk into the ground; these were 50 feet long, 22 feet

wide, and 7 feet deep. The tower consisted of two platforms and a laboratory

at 896 feet for Eiffel’s use. All sections of the tower were prefabricated; seven

million holes were drilled off-site, and remarkably there were no significant

difficulties with on-site assembly.

The precision of the planning shows up in the contract presented here.

For instance, one curious but highly specific detail is the reference in Article

2: “Widow Bourouet-Aubertot, owner of the hotel on the avenue de la

Bourdonnaye, 10.” The widow had approached the Prefect of the Seine

threatening to require demolition of the Eiffel Tower, which was in the midst

of construction. The contract states: “The aforementioned widow has

withdrawn a provisional execution of a judgment to intervene.” That settled

the matter, and in the process made the Widow Bourouet-Aubertot forever

famous or infamous. Her story is just one of many complaints from abutters,

interested parties, affected parties, and others whose viewpoints Eiffel had to

confront.

Article 3 of the contract is noteworthy for more substantive reasons. It

addresses park landscaping, which would be disturbed by the tower

construction. The contract stipulates that Eiffel will be responsible for any

plantings moved, and “will support the costs of removal by the gardeners of

the city the trees, bushes, and plants that must be displaced.” Note that the

city’s gardeners would do the work, not a work crew of riveters.

Another concern in Article 3 was: “Mr. Eiffel will not cause any

changes to the hydrants, sewer drains, or water pipes situated in the Garden of

the city.” Here we learn of the exquisite city planning for Paris, which located

a water source under the park. There are two advantages to such a placement.

First, the water pipes could be used to assist in irrigation of the plantings.

Second, the pipes are located beneath a surface that is subject to little

vibration except running children; hence there would be few disturbances to

the critical infrastructure of the Parisian water system. Gardeners and students

of Indian architecture might recall that the Taj Mahal used a similar design,

locating water pipes under the gardens.

Les Egouts (the sewers) of Paris remain a tourist highlight, with an

entrance beneath one of the bridges crossing the Seine. The sewer was

designed during the administration of Haussmann, Napoleon III’s famous

Prefect of the Seine. Paris had been one of the unhealthiest cities in the world,

assailed by repeated epidemics. Haussman insisted on cutting wide avenues

that provided fresh air, thereby opening up narrow streets that had remained

unchanged since medieval times.

Another portion of the contract presented here provides specific

guidelines for the use of the Eiffel Tower in case of war. In Article 8, Eiffel is

instructed: “In order to facilitate scientific or military purposes or use, Mr.

Eiffel will reserve on each floor a special room which will remain free for the

disposition of persons designated by the Minister of the General

Commission.” In a note of finesse, it is added that said Minister will get 300

free admissions per month and the admissions can use the elevators.

Eiffel Tower 8

Article 13 requires that in times of war or a state of siege, the

government will have the right to use the tower, perhaps for its vantage point

as a lookout, but more likely for sending signals. The contract is meticulous in

outlining how Eiffel will be repaid for time lost during military use, and

provides that “the term of concession will be extended one year for every

period of three months or fraction of three months during which the

suspension occurs.”

A discussion of the construction of the Eiffel Tower is not complete

without consideration of the elevators. Never before had ascenseurs risen to

such heig

Article 13 requires that in times of war or a state of siege, the

government will have the right to use the tower, perhaps for its vantage point

as a lookout, but more likely for sending signals. The contract is meticulous in

outlining how Eiffel will be repaid for time lost during military use, and

provides that “the term of concession will be extended one year for every

period of three months or fraction of three months during which the

suspension occurs.”

A discussion of the construction of the Eiffel Tower is not complete

without consideration of the elevators. Never before had ascenseurs risen to

such heights. The French company Roux, Combaluzier and Lepape built the

first elevators, which carried passenger to the first platform by means of

hydraulics, utilizing a double-looped chain for extra safety. In 1897, those

elevators were replaced by equipment from the French firm Fives-Lille; these

lasted 90 years until they were improved in 1987. But even the Fives-Lille

company only had the technical know-how to bring the elevators to the first

level.

How could visitors get further without climbing the endless stairs

upward? This was a task for the world’s best-known elevator man, Elisha

Graves Otis. In 1853, Otis introduced the world’s first safety elevator in

Yonkers, New York. From that point on, buildings could rise beyond the

limitations of stairs. In one of his greatest works, Otis designed elevator

cabins as two-decked rooms mounted on sloping runners and pulled by a cable

that was powered by a hydraulic piston.

The piece de résistance was the vertical lift designed by Leon Edoux

to bring visitors to the top of the tower. Passengers changed cars halfway up,

as only one car could continue upward, counterbalanced by the other going

down, in a design not unlike a water clock and similarly powered by water

tanks that helped provide the hydraulics. Of course, Edoux’s ingenious

engineering did not work in the winter when frozen water in the tanks made

operations impossible until the spring thaw. Edoux’s marvelous invention

operated until 1983 when technology had advanced sufficiently to offer a

replacement.

At his own risk—and his own profit—Eiffel was free to conduct the

construction in any manner he chose. He also was given the right to fix the fee

for admission to the tower: higher on weekdays than on weekends. In return

for these allowances, and for the right to lease and collect rents from the shops

and cafés associated with the tower, Eiffel was required to pay 1,000 francs to

the Exposition Commission. Eiffel was also legally bound to pay the City of

Paris for rental of the land on which the tower was built—a nominal 100

francs per annum

The contract for building the Eiffel Tower contains insurance

provisions, a feature lacking in many other contracts of similar vintage. Eiffel

was required to put aside one percent to cover potential expenses for sick or

wounded workers. In addition, Eiffel was bound to set aside a reserve fund to

deal with accidents. It should be noted that there were no fatalities during the

course of the construction—a tribute to Eiffel’s well-orchestrated planning.

The one recorded death of a workman occurred off site and off duty.

Like his fellow engineer/entrepreneur, John Roebling, who built the

Brooklyn Bridge in the United States using steel ropes manufactured in his

own factory in New Jersey, Gustave Eiffel built the Eiffel Tower six years

later utilizing a similar management process: coordination of on-site work

with ongoing construction being prepared in his own nearby factory. Both of

these mechanical engineers were not just designers but also business owners

and managers—Eiffel was Mr. Iron, and Roebling was Mr. Steel. Both built

structures higher than had ever been done before.

The tower bears the names of 72 of France’s greatest technical minds,

18 luminaries on each of the four sides of the base. For most French people,

however, one name is mentioned even more frequently than Eiffel’s:

Monsieur Poubelle, the Prefect of the Seine, who signed the contract featured

here on behalf of the government. M. Poubelle is the inventor of the garbage

pail, which is still used all over Paris and France. The ubiquitous receptacle is

actually called a poubelle.

IMPORTANCE IN HISTORY

What distinguishes the Eiffel Tower is not just its beauty or

symbolism. Like the Colossus of Rhodes, it was a technological marvel of its

time, pushing the limits of existing engineering knowledge. It is a little known

fact that Eiffel helped build the Statue of Liberty in New York harbor. In

1885, he worked with Frederic Bartholdi to create the wrought-iron pylon

inside the statue.

Eiffel was duly recognized for his tremendous achievement. On the

200 franc banknote (the currency of France before the adoption of the euro in

2002), there was a depiction of Gustave Eiffel and on the reverse side, the

Tower. It is a distinction afforded few engineering projects, and a sign of his

place in French history. Even in France today, the top of the social hierarchy

is not, as some might imagine, painters, designers, or aristocrats, but instead it

is engineers.

While standing at the top of his completed monument, Gustave Eiffel

proudly received the Legion of Honor, inducting him into that elevated society

that has given special distinction and national renown to France.

The Eiffel Tower has made such an impression on the world that it

was especially honored in Shanghai, China in a cultural exchange featuring

the Oriental Pearl TV Tower, built for telecommunications, and one of the

world’s highest buildings (468 meters or 1535 feet).

Eiffel continues the tradition of Les Grands Travaux as a worthy

successor to Pierre-Paul Riquet (the Canal des Duex Mer), Ferdinand de

Lesseps (the Suez Canal), French-born Isambard Kingdom Brunel (the RMS

Great Eastern and the Thames Tunnel), and more recently Louis Armand

Thanks for the nice article! I'm living 10 min from the Eiffel Tower, but didn't know most of what you wrote!

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

thank you so much for watch my blog

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

https://www.amazon.ca/Hitler-Paris-Photograph-Shocked-World/dp/075654789X

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

I have already delete this

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Congratulations @nazmul8877! You have completed some achievement on Steemit and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click on any badge to view your own Board of Honor on SteemitBoard.

For more information about SteemitBoard, click here

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPDownvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit