Recently, a rare and powerful storm hammered the East Coast of the United States with swell and dangerous winter weather. Unofficially, the storm was known as Winter Storm Grayson, a name that will be used by the masses when reflecting back on the record-setting cold that opened the new year — that is, as long as you don’t work for the National Weather Service. Now, the eastern half of the US is preparing for Winter Storm Hunter to usher in more snow, ice, and freezing temps. And yes, it will bring more swell too.

Back in the fall of 2012, The Weather Channel began the practice of naming winter storms, akin to the naming of tropical storms, with Winter Storm Nemo. The weather and science community was fairly unified in their reluctance to fall in line with this practice, going as far as the NWS expressly directing forecasters to not use winter storm names in their forecast products. But since that start in 2012, the practice of naming winter storms has gathered some momentum and that steadfast view appears to be softening within some groups.

Surfline

✔

@surfline

What are your thoughts -- should we use names (like Hunter, Grayson, Jonas) when discussing winter storms?

1:52 PM - Jan 12, 2018

37%YES - easier to follow

50%NO - name hurricanes only

13%Huh? I live in da islands

142 votes • Final results

8

See Surfline's other Tweets

Twitter Ads info and privacy

After a hyperactive, storm-filled winter in 2013-14, the UK Met Office and Ireland’s Met Eireann began naming storms in the winter of 2015. This made storm names an official standard across all platforms in the region, including media, to reduce the threat of confusion during very active periods.

At Surfline, we’ve admittedly been hesitant to adopt the use of winter storm names. The primary reason being that naming winter storms is still not accepted by the scientific community. However, our view too has softened over past few years, evidenced by our use recent use of the name Grayson.

The naming convention for tropical cyclones was solidified in the 1950’s and is widely accepted and understood, so what is the issue with using winter names? The most glaring difference is that a private and for-profit media company, The Weather Channel, made the unilateral decision to name winter storms, not a governmental, academic, or research-based institution, like the National Weather Service, NOAA, or even the American Meteorological Society.

Tropical cyclones are also well-defined in terms of location, strength, track, and area of impact — winter storms, not so much. A winter storm can have a less defined or even multiple centers, much broader areas of significant weather impacts that are far removed from the actual storm location, and multiple types of impacts over a vast area.

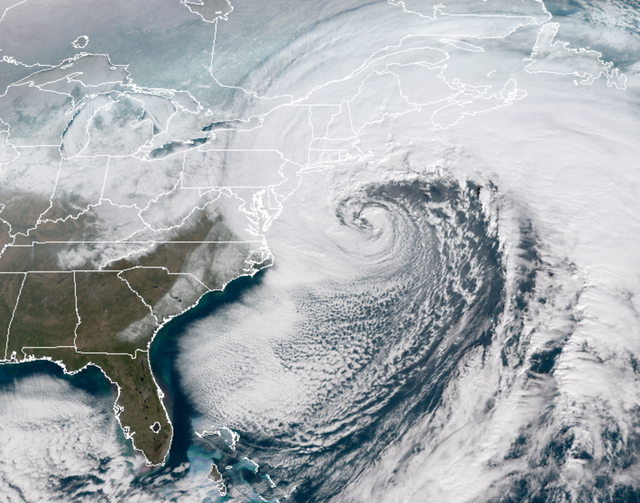

Winter Storm #Grayson (above) is long gone. Now Winter Storm #Hunter is on its way to disrupt the East Coast and provide more surf opportunities.

Still, one of the biggest hurdles to name acceptance is who is making the call. Without an official naming standard or agency, the scientific community remains hesitant to follow growing public acceptance. While tropical cyclone naming convention is clearly defined, the Weather Channel alone determines naming based on National Weather Service winter warnings and/or the potential number of people affected over an area — meaning the denser the population in a storm’s path, the more likely a storm is to be named. The UK and Irish Met Office’s naming is determined similarly and is based on potential damage, but the naming comes from an official source, the governmental meteorological agencies themselves.

One has to wonder, would a storm that ravishes the Outer Banks but heads out to sea be treated equally to a similar, or even weaker, strength storm that slams into the Northeast? And if the public becomes accustomed to winter storm names, will they still heed winter weather warnings for their local area if there is no #name attached to the storm, even if local impacts are just as severe? A tropical cyclone is named it meets strict criteria, not only if it threatens land or lives.

So what is the benefit of naming storms? We have been unofficially naming non-tropical storms for centuries, only these names typically come along after the storm event has passed, much like we surfers name swells. Unique, memorable, and destructive storms (or swells) are often assigned names associated with when they occur, offering all an easy way to reference a specific event — many remember the Perfect Storm/Halloween Swell (1991) and the Storm of the Century (1993) on the East Coast, or 100ft Wednesday at Mav’s (2001) and the Columbus Day Storm (1962) on the West Coast.

Winter storms bring winter swells. Cold, raw, and powerful, name or no name. Photo: Pat Nolan

The most obvious benefit from naming winter storms beforehand is the same for why we’ve named them after the fact — it gives an easy and single point (name) of reference. And in the modern-day, hashtag-dominated, social media world, it’s a lot easier (and takes fewer characters) to use #Grayson versus ‘an intense, sub-960mb winter storm nor’easter that will impact the East Coast’ to disseminate information, whether it’s for a blizzard warning or surf alert. Surfline has acknowledged that there is a benefit to this easy reference tool, and it’s the driving force for why we have started dipping our toes into the named winter storm waters.

But does it make a difference to the general public? The UK Met Office reported preliminary findings after they began naming storms that it “improved people’s ability to understand the risks of severe weather and… made people more likely to take action.” But a recent study published in the journal of the American Meteorological Society isn’t as generous. Lead researcher Adam Rainear found “little difference exists between individual perceptions dependent on whether a name is used” and people do not take media coverage more serious based on a storm name. The author acknowledges that more study and understanding is needed and warranted.

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

http://www.surfline.com/surf-news/does-the-business-of-naming-winter-storms-help-or-hinder-the-public-whats-my-name-winter-storm-names-gaining-a_151366/

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit