(cross-posted from my substack)

Beliefs and Motivation

Do moral beliefs motivate action?

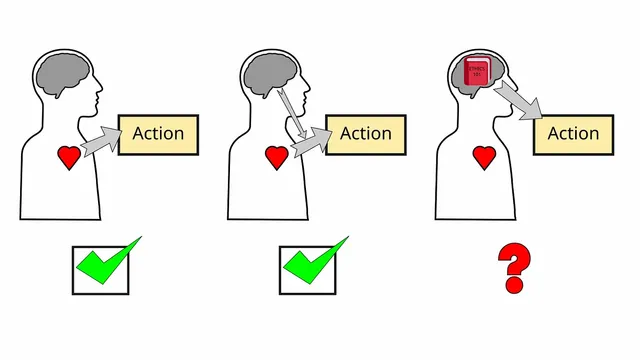

A few weeks ago I read a philosophy paper that brought up an interesting topic: Do Moral Beliefs Motivate Action? by Rodrigo Díaz. There has been an argument since David Hume that beliefs, by themselves, don’t motivate action. Consider: believing that there is food in the refrigerator probably doesn’t cause you to take any particular action, but if you are feeling the drive of hunger then your belief about food and the refrigerator might shape what particular actions you take. But what about moral beliefs? Can a belief like “People should donate to charity” by itself motivate someone to donate to charity, or do you need some sort of drive (perhaps the desire to feel good about being generous, or a desire to be admired) to motivate actions like that? That’s the topic of the paper.

I thought it was an interesting topic from a game design perspective, because issues about what players should do and what players are motivated to do seem very relevant. For example, in the AD&D Dungeon Masters Guide, Gary Gygax asserted “You can not have a meaningful campaign if strict time records are not kept.” That raises the question: even if he convinced a reader that keeping strict time records was the right thing to do, does that get them to do it?

Moral Emotions

The paper points out that the topic can be difficult to explore, because in addition to having moral beliefs we also have moral emotions. For example, anger tends to motivate us to act against rulebreakers or norm-violators, but the distinction between the belief that an action deserves punishment and the drive to do the punishing can seem a little mushy. The researcher ran two studies for the paper using some pre-existing psychological scales to try to probe whether constructs based on moral belief or moral emotion seem more correlated with relevant actions. The results are a bit equivocal, but he interprets the “it has to go through the emotion” story as being more supported. Aside from whether or not the numbers are compelling, I’m not thrilled with the questions used in the psychological scales (I think this is more a criticism of the moral psychology research landscape than of this particular paper for using these measures), so I’m not sure there’s a lot of strong conclusions that can be drawn from the experiments. However, the “you need a separate drive, beliefs don’t do it on their own” analysis does make sense to me, so I found the paper valuable for presenting the topic in this way even if I don’t find the experimental data very compelling.

Regrets, I’ve had a few

It seems to me that avoiding guilt and regret can have the function of motivation even in purely “the rules say you must do X” type situations. The paper largely frames the issue as a binary do they/don’t they question about beliefs, but if we go a step deeper we could also speculate that different motivations may be subjectively different. My intuition and experience is that negative-avoidance types of “motivation” are more draining and grinding than when your actions are more positively motivated. One of the classic problems with traditional tabletop RPGs is that a GM can experience burnout from the workload of doing so much prep. Some games endeavor to make aspects of prep work into fun and engaging experiences in their own right, and that strikes me trying to align play procedures with the drives of the person performing them rather than relying on the purely obligation-based “you have to do this work now or else other people won’t be able to have fun later” model.

Takeaways

From a game design POV this beliefs/drives model of motivation suggests to me that failing to have a necessary action grounded in some sort of natural human drive or emotion could be a potential breakdown point with a design. For example, some games have a back-and-forth structure that works fine in steady-state once players are hitting back for things that happened in previous rounds, but getting the chain started can be a problem because there’s insufficient motivation to take an initial action. Anger seems like it’s the easiest emotion to employ as a motivator since it relates to perceiving situations, but anger is also not always pleasant so overusing it may not be wise.

In a sense any voluntary action you take in a game ought to be an opportunity for a form of self-expression, which I think can plausibly be said to be a pretty deep human drive, but the conditions need to be right for that to manifest (for example, the player needs to be able to see actions they can take that feel authentic to express). But designs sometimes have needed “maintenance” type actions – where the game needs something to be done in order for the system to function but isn’t grounded in player agency – and these may benefit from considering motivations beyond just telling players that these things need to happen (and a GM is a type of player).

The flip side of not taking actions when they’re needed is actions taken that aren’t conductive to the game. A not-infrequent problem with TTRPGs is “turtling” where players choose to use their actions and resources to entrench themselves in a situation of relative safety, even though that tends to lead to less interesting fictional events than leaving vulnerabilities exposed (dramatic!) or pushing into previously-unexplored areas (novelty!). It seems to me that this will tend to happen when a self-protective drive is the only motivation players are feeling, so rather than moralizing this as bad player behavior it could be a sign that the game’s design isn’t providing enough salient alternative motivations but is still prompting the player for actions so they end up choosing a self-protective default.

I also suspect that thinking in terms of actions requiring a motivating drive suggests this won’t be a big consideration for inaction outside of motivations – keeping something outside the bounds of play or against the rules probably doesn’t need much independent motivation to not do it, just belief that it’s not appropriate it probably good enough for that.

I think this drives/beliefs framework is also helpful to me in thinking about why certain “reform” approaches fizzle. For example, even if people are convinced that having a culture of playtesting is the right thing to do that doesn’t by itself get them to do it. And the excitement and anticipated positive feelings of following the “hype first” model are hard to beat without having alternate drives to appeal to.