I originally wrote this blog post about playtesting tabletop roleplaying games in early 2015, but I'm republishing it here with minor edits.

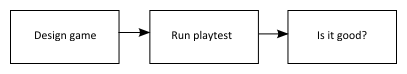

A high-level black box model

Breaking things down to low level concepts, what we want to know when we playtest a game is whether the result of the design is good or not, so we can figure out the next step to take, such as taking the game back to the drawing board, finalizing the game to publish it, etc.. Drawing that in simple diagram form might look like this:

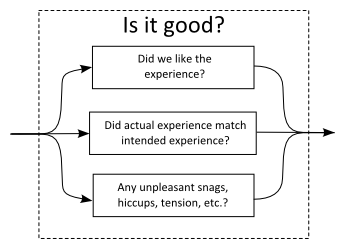

Looking inside the boxes

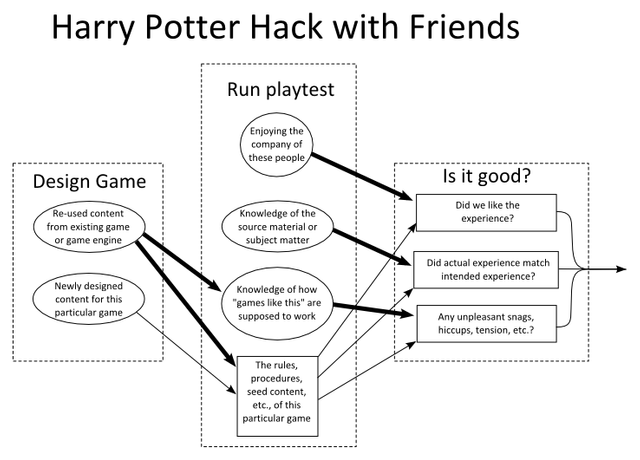

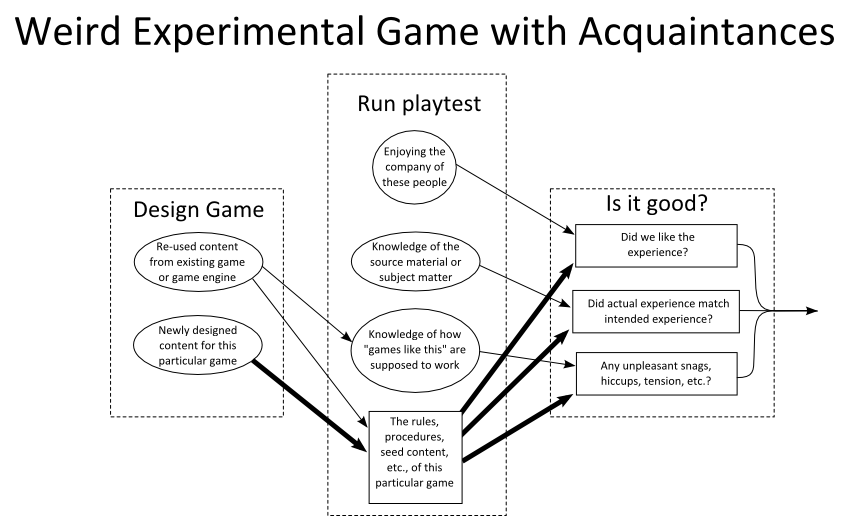

But we don't have to leave things at this black box level, let's peek inside the “is it good?” box. Obviously this is a complex question, but we might choose to abstractly model it as some combination of several factors, such as “Did we like the experience?” (if the answer is 'no' it's probably not a fun game), “Did the actual experience match the intended experience?” (if you had a very Star Wars-like experience and you were trying to design a Star Trek-like game it's probably not a good Star Trek game), and “Did the game run smoothly, or were there unpleasant elements like rules confusion, uncomfortable interpersonal tension, difficulty figuring out what to do next, etc.?”.

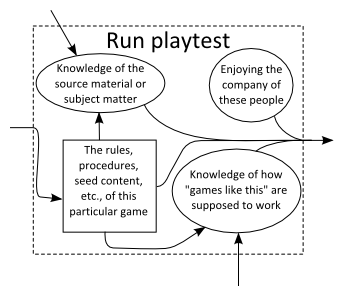

If we peek inside the playtesting box, we might think about several things that contribute to an RPG session. Obviously the particular rules, procedures, background information, etc., that make up the game being tested will be a factor. But there are other factors, too. The chemistry of the people you're playing with certainly influences play. And of course no game exists in a vacuum, every player brings things to the table with them, such as customs, habits, or expectations built by playing other games. Also, since RPGs take place in the imaginations of the participants, pre-existing knowledge of the source material matters, too: from low-level issues like vocabulary to more complex expectations like “what an orc looks like”. Recognizing that any model will be imperfect, we might choose to model the playtest like this:

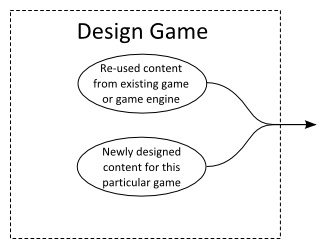

And of course, we can go inside the black box of designing a game, too. All art both builds upon what has come before and makes its own contribution, so to a greater or lesser degree any given game will be using pre-existing concepts and also bringing new ideas to the table. Some games might re-use a lot of existing concepts, such as when someone heavily leverages an existing design framework, and some games might lean more toward original material, such as a blue-sky experimental game with lots of never-before-seen mechanics and techniques.

A tale of two groups

Now that we've got some conceptual models to work with, let's imagine two playtest groups so we can compare and contrast. In the first group, the designer has taken a game that his group loves playing and has hacked it to support something else they all love, Harry Potter. They have all known each other a long time, enjoy hanging out with each other even when they're not roleplaying, and they follow an “as long as you're having fun you're doing it right” philosophy toward gaming.

In the second group, the designer has created a weird, new experimental game to produce roleplaying experiences similar to an obscure genre of literature that she enjoys. They're acquaintances that don't know each other that well, but they've all bonded over a mutual interest in following the rules of each game as closely as possible so they can have a unique and different experience with each game they play.

If we plug our Harry Potter Hack design into our white-box conceptual models, we can see some things:

First, we can guess that they'll probably have a good time, because these people enjoy each other's company. Also, because the game-under-test is a hack of a game that all the players are familiar with, odds are good that they'll be employing a lot of pre-existing habits and expectations while they play, so they'll probably get up to speed quickly, but might forget about or gloss over some of the new design elements. Since the game re-uses a lot of the structural elements from the base game which already functions well they probably won't run into any catastrophic breakdowns. And since all of the players are very familiar with the source material, their game decisions will probably be heavily influenced by “what would be the Harry Potter thing to do?” thinking, regardless of where the particular mechanics of the game would be guiding them.

If the Harry Potter group has a fun, enjoyable experience in the playtest, what can the designer conclude? Well, it's certainly possible that their design work was the main contributor to that, but since there are so many other strong signals that would also lead to that result it's difficult to make that conclusion: this group might have an awesome time even if they were playing a terrible Harry Potter game as long as they could say “Wingardium Leviosa” while miming a swish-and-flick motion as they rolled their favorite dice. If the session turns out all wrong that's probably strong evidence that there are issues with the design, though, because the other influential factors are unlikely to produce that result.

What about the group playtesting the weird experimental game?

Since the game is highly, perhaps painfully original, the group is unlikely to substitute in any pre-existing expectations from other games even if they wanted to, which they don't because they're deeply invested in trying to play each game on its own terms. They don't know how these types of stories are supposed to work, so the only thing they can do is attempt to follow the rules and procedures in front of them. And they don't know each other that well, so the pleasant experience of spending time with good friends won't really be a factor (obviously they might become friends, but they're not yet).

If the weird, experimental group has a fun, enjoyable experience in the playtest, that's probably good evidence that there's good stuff in the design. If the game doesn't use any tried-and-true techniques, merely getting to the end without the wheels falling off is a nontrivial accomplishment, since it means that many things that could have gone wrong actually didn't. If the session gives the correct vibe for the source material, that's probably due to the game design, too. And if it was fun, again, there's a good chance it's because of the game design. Obviously these things can never be known with absolute certainty: maybe these people just have awesome chemistry together through random chance, and maybe mere luck kept the game from crashing and burning. Still, it's evidence that didn't refute the hypothesis “this is a good game”. What if the weird, experimental playtest session sucks? Well, it's a bit harder to draw conclusions there. Maybe these people are just incompatible in some way and shouldn't play together. Maybe the obscure genre is an acquired taste, and the group disliked their first experience with it but would love it if they got to know it. Maybe they're bringing in baggage and expectations from other games despite their intentions, since their self-described gaming attitude isn't evenly distributed across all gaming subcultures. Or maybe they're still in the “learning curve” part of the game and they'd start having fun once some system mastery kicked in after a few sessions of experience.

Different, Not Necessarily Better or Worse

These approaches are different, but whether that means better or worse depends on what you were trying to get out of it. If the goal of the playtesting is to get the maximum amount of information about the quality of the game design, the experimental “rules as written” group is probably getting closer to that goal than the Harry Potter group. If the priority is to have as high a chance as possible of having a fun session, the Harry Potter group is more likely to get that result while the other group might have to console themselves with feelings of nobility and integrity as they go down with a sinking ship of a game design that didn't work. (Personally, I think that it makes the most sense to prioritize playtesting for the sake of getting information about the game design, because if your goal is to have fun why not just play an existing game that's known to work well instead of taking the risk on a playtest?)

And, naturally, the two abstract examples I described don't represent the only two ways to do things, I selected them to illustrate the point that the way you choose to design and test a game influences the information you can get from playtests and the conclusions you can draw from the process.

Playtesting is an important part of any game creation. Whether it is a new rule system, new setting, or just a one-shot adventure in an established rule system/setting. I run RPGs at conventions and I really like to playtest the ones I am not sure about before I put them in front of a potentially unknown group who decided to spent a few of their available hours playing my game. It gives me a chance to see what works, what doesn't, and see if any additions can be made to make the game better.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Hi @danmaruschak! Thanks for your Steemit contribution.

My name is @hounddog and I am a bot that reads every post on this platform and connects similar content. I want to help people find publications that they like, so rewards are distributed fairly. Based on the content of your post, you and your readers may also be interested in these publications:

1: The Wonderful Simplicity Game A Hat in Time Game Review by Aymenz by @aymenz (92% match)

2: Real Farm DLC Review The pleasant learning curve by @lyra.roberge (92% match)

3: My Personal Top 5 PC Games of ALL TIME! Gaming Top 5 Part 54. by @techmojo (94% match)

If you want to know more about me or get some personalized recommendations, CHECK OUT MY NEWEST PUBLICATION!

Have a nice day and sincerely yours,

HoundDogDownvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit