I've been listening to Solzhenitsyn's unabridged Gulag Archipelago in audiobook format recently (and will be for a while, given its magnitude), and It's got me thinking about why I make games, and why people play games, which I've talked about before but not really ever given a concrete example of.

One of the big emphases in Solzhenitsyn's work is that Gulag Archipelago is about memory, it's about history and about making sure that mistakes that were made in the past can never be repeated in ignorance. It's about crying out for retribution not for the sake of the victims but so that in the future oppressors will know what the cost of their actions will be.

It's an invective against naivete.

What Solzhenitsyn writes to accomplish is to open the audience's eyes. He does not imagine a world without sin, but rather a world in which sin is recognized for what it is.

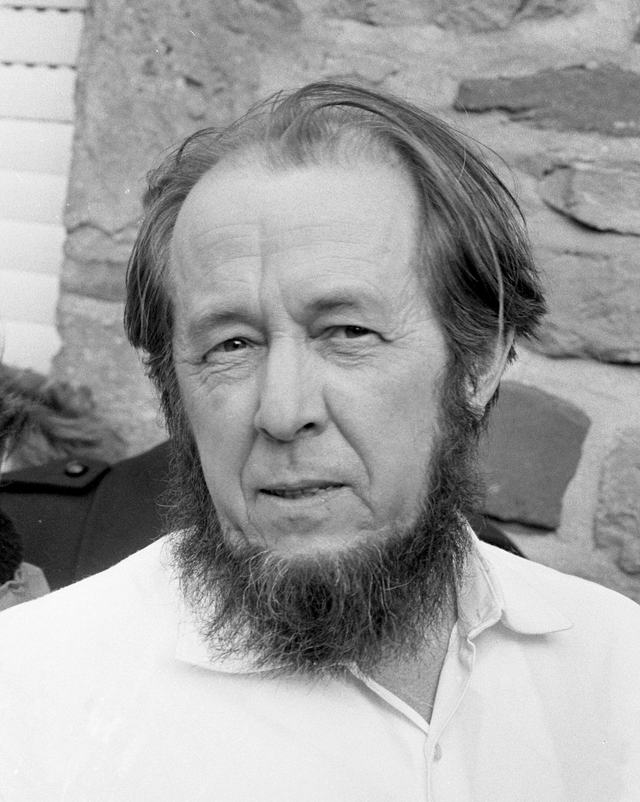

Image of Solzhenitsyn from the Dutch National Archives

And as a game designer, creating games that encourage storytelling is the main objective I have. I don't require these stories to necessarily carry heavy meaning, have some deep complexity, or bear light to the greater Meaning of existence. Rather, it is sufficient for these games to simply provide a platform, a framework, in most cases.

I do not typically seek to tell the stories that the systems I create shepherd. I like to encourage people to look beyond numbers, beyond simple equations and processes of interpolation and extrapolation.

But one of the things that stands out to me and reinforces my conviction in my efforts is the fact that I know for a fact that games can have great meaning and purpose, and shine a light on the greater truth of the universe.

Of course, this is possible in microcosms and instants. Every story, after all, plays into the grand overarching archetypes, themes, and structures which flow from the deepest roots of reality itself; through them we can learn to see what our eyes are blind to. So any time a story is told, even if it is inexpert and artlessly told, it has a potential to bring enlightenment. Perhaps it will be what one person, perceiving it in a half-interested manner, needs to get past a cognitive block or dig deeper into the world.

And the number of cases in which people have drawn motivation from fictional characters who serve as role models and fictional events that serve as mirrors of reality are innumerable. People cite the characters of Homer and Shakespeare, the great bards, and countless other writers, as holding the keys to their own life.

As I have been walking with Solzhenitsyn, him recounting events I have never experienced–and, God willing, never will–I have received again a reminder that stories are the way that we learn about our world, more so than any analysis and logic. It is complex and abstract language, and the creations that depend upon it, that separate humanity from other creatures. Of language and stories, however, the stories are more pivotal.

I have recalled to mind an older game by a now fairly well known independent publisher as I think about Solzhenitsyn's case. Grey Ranks (affiliate link) is an example of a game that serves as a foundation for telling a meaningful story.

There are several things interesting about the game itself, but I am not here to review it or give an account of its contents so much as I am to muse on the reason why it is important and interesting.

The first and foremost asset that Grey Ranks provides to the world is that it is a recollection of history, a grim but accurate depiction of one of humanity's darker hours–I remember being as shocked years after I had read Grey Ranks that the Red Army had waited across the Vistula as Warsaw burned (the impetus for this shock being a historical text, though I cannot recall which), in indignation rather than ignorance–so to that extent the game harnesses the human instinct to play to provide information and extend the person beyond the personal.

So to this extent it is the case that a game manages to provide players with something useful in the form of information.

But information is easily acquired, and easily forgotten, on its own. How will such a game provide anything of lasting value, or remain meaningfully enough that a casual observer who has read hundreds of games will remember it well enough to have it spring to mind via association upon hearing about the Warsaw Uprising even in passing?

The answer lies in the archetypes, and the most important archetypal theme–sacrifice.

What Grey Ranks depicts is sacrifice; people desperate and longing for anything but what they will have to endure, but who know that the alternative is to lie down and die like sheep. The events of the game follow an unsuccessful resistance–and there is no course of events that can change historical fact–but do so in a deeply personal, connected manner.

By making the audience care about the roles they are playing, by making them consider the weight of their actions, they transcend the mean and base. They rise to a point of ennoblement, of enlightenment, tearing at the heavens in pursuit of this knowledge.

It is my hope to one day make such a game–right now, I simply create frameworks and tools. However, as my work is refined by practice and effort, I approach such a goal.

Interesting approach. It actually reflects much of what I think about writing and storytelling myself. Tabletop roleplaying games in particular, given the investment they require from players, are a great tool to provide the players with a deeper understanding of events, concepts, or information in general.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

It is a slight bit optimistic in the sense that the vast majority of games are never going to hit this point.

I'm starting a second running playtest of Hammercalled, now that it's mature enough to have a significant amount of ongoing playtesting without causing the changes to be so mercurial that players in the games wouldn't be able to keep up, and I'm going to experiment with a more deeply philosophical feel to the game, to such an extent as it is possible, as it takes place in a dystopia influenced by Solzhenitsyn.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Your post was upvoted by the @archdruid gaming curation team in partnership with @curie to support spreading the rewards to great content. Join the Archdruid Gaming Community at https://discord.gg/nAUkxws. Good Game, Well Played!

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit