The top 5 publicly traded corporations in the United States by market cap in 2001:

General Electric, Microsoft, Exxon Mobil, CitiBank, and Walmart

Total Value (Market Cap in $) = ~$1.5 trillion

The top 5 publicly traded corporations in the United States by market cap in 2018:

Apple, Amazon, Google, Microsoft and Facebook

Total Value (Market Cap in $) = ~$4 trillion

Much of the value created in the economy over the past two decades has been driven by the Internet. Much of that value has been captured by Internet-based companies. The upper echelon of publicly traded corporations has seen a changing of the guard. The aggregate value of the top 5 US corporations by market cap today is more than double what it was in 2001. Why are all these companies so much more valuable than those built in a pre-Internet world?

A statistic might give us some clarity. As of 2018, Facebook reported 2.19 billion people used its social network daily. There are roughly 7.6 billion people on the planet, half of which don't have internet access. Of the people that do, more than half use Facebook every day.

Could you imagine if 2 billion people in the world used CitiBank? They manage roughly 50 million accounts today.

The most valuable companies are the ones with the most defensible and lucrative moats. The top 5 companies by market cap in the US at any given time are essentially monopolies. The changing of the guard in the first two decades of the 21st millennium is a shift from monopolies built in a world of physical scarcity to digital ones built in a world of abundance.

How has our world shifted from one of scarcity to one of abundance?

In a world of physical scarcity, you could only reach consumers through physical means. Geography was a constraint. If you wanted to publish an article, you had to print physical copies for each person you wanted to serve (which incurs a cost) and then you have to figure out a way to get it in their hands (incurring another cost). Sending a product to someone in New York incurred a different cost than sending that same product to England. Serving consumers at scale with this model is not very cost-effective.

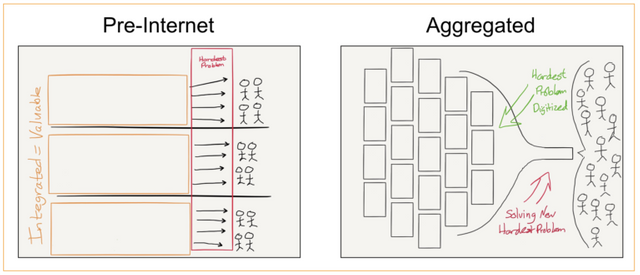

Distribution at scale, because of its costliness, became a moat. Companies willing to invest in distribution took advantage of that moat and integrated with suppliers to create natural monopolies. In a world where the marginal cost of reaching and transacting with each consumer was high, it was easier and cheaper to control supply, not demand.

The Internet turned this dynamic on its head, lowering the cost of distribution by orders of magnitude. On the Internet, the cost for your article to find its way onto a reader's screen is effectively zero, regardless of geographic location. You no longer needed the New York Times, with all of its printing presses and delivery trucks, to reach readers at scale. The Internet made it economical to serve 2 billion people.

The Internet also transformed the supply of goods. Anyone on the web can publish content - whether that's articles, books, music, video, or software. Publishing is permissionless. The cost of distribution, which previously served as a barrier to entry for suppliers, converged to zero. Suppliers all over the world published their content on the web virtually for free. We moved from scarcity to abundance.

Yet, in a world of abundant supply, how the hell do users find what they're looking for?

Google built an $800 billion business on solving this very problem. In a world of abundant content, you can provide value by helping users find exactly what they're looking for. Many internet businesses today have achieved success in solving the problem of search and discovery within niches. You could call them matchmakers.

Amazon and eBay help buyers find sellers and vice versa. Spotify helps you find new music that you'll like. Uber connects people who need a ride with people who can give them one.

And these companies all do this at unprecedented scale.

Curiosity compels us to ask a few important questions. How did Facebook come to amass more than 2 billion users? Why were no other social networks able to do the same, or even come close? Twitter, Facebook's closest competitor, only has 300 million users.

The short answer: people don't want to choose between 5 different social networks that all do the same thing. They just want to pick the one that's most useful and stick to it. A social network is only as valuable as the people on it. Facebook built its moat by offering a great user experience that attracted users, who invited their friends and family, which made Facebook more valuable to each user. More users spending time on Facebook means spending less time on other social networks (RIP Myspace), which reduces the value of those networks to existing and potential users. All those users go to Facebook, because that's where everyone else is.

This positive feedback loop is more commonly known as a network effect. When the value of a product or service increases for each additional user, you have a network effect. It's easy to understand why social networks are the purest expression of network effects. A dating app with no people on it is the worst dating app ever. But a dating app with lots of people provides a much better experience.

Many of the most successful internet companies today can attribute their success to coming out on top of a winner-take-all market. Not all of these companies are social networks. As it turns out, there's more nuance required to understand how these companies created their moats.

We can apply our simplified definition of network effects to non-social networks. Amazon is the Everything Store. A store is only as valuable as the products that it stocks. As the name suggests, Amazon is valuable because it stocks everything. Yet Amazon doesn't even manufacture most of the goods it sells. How can they sell everything, but manufacture nothing?

Recall that the Internet reduced the marginal cost of reaching each user. In a world of abundant supply, leverage shifted from controlling supply to controlling demand (there's simply too many suppliers and users don't have the time or energy to sort through them all!). The competitive advantage is in establishing a direct, exclusive relationship with users at scale by focusing on creating the best user experience possible (help them find what they want).

The Amazon you see today looked much different 10 years ago. Before, they focused on narrow product categories like books and consumer electronics, and differentiated via superior selection and price. They created Amazon Prime, which was an incredibly compelling user experience via convenience. Amazon established direct relationships with consumers it had, which gave it power over commoditized suppliers. Those suppliers, struggling to adapt to a world of abundance, had no choice but to come onto Amazon's platform to reach end users. More suppliers means more product selection, which increases the value of Amazon to all users, which attracts more users. More users attracts more suppliers, and the cycle continues.

From Ben Thompson's Stratechery.com

The positive feedback loop enjoyed by companies that leverage their control of demand for abundant resources to attract commoditized suppliers onto their platform, creating a virtuous, winner-take all cycle of supplier and user aggregation is known more commonly as Aggregation Theory. Coined by Ben Thompson, Aggregation Theory encapsulates how new companies have disrupted legacy industries. With new business models uniquely enabled by the internet, companies now can operate at a scale previously thought impossible.

$4 trillion doesn't seem like such a big number after all. Especially not in our new world of abundance.

Wow it is really wonderful. nice sharing dear. You are a newbie. I appreciate your effort. good luck for future

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit