The photographs record a 1967 antiwar demonstration in Central Park, a 1968 protest at Columbia University and an undated “gay power” demonstration. There is film footage of the first Earth Day march and a rally held by the Nation of Islam.

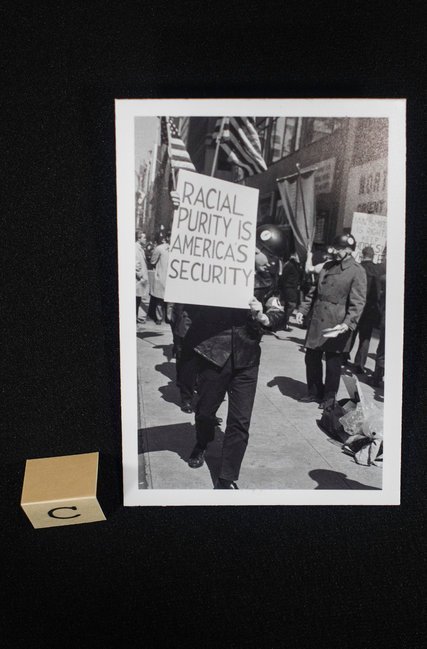

One image from 1970 shows the ruins of a West Village townhouse accidentally destroyed by Weather Underground radicals who were making a bomb. Another depicts neo-Nazis in 1972 demonstrating outside the Rhodesian embassy in Midtown Manhattan.

The photographers were almost all police officers; the images all evocative markers of New York history. Now they are the focus of a new exhibit that explores how the police and their surveillance work came to create an expansive record of a tumultuous era.

“They assembled this amazing trove of artifacts that document the early days of the civil rights movement, the early days of the gay rights movement, the launch of environmental activism,” said Pauline Toole, commissioner of the city’s Department of Records and Information Services, which is hosting the exhibition through February.

Continue reading the main story

But the show, at the Surrogate’s Courthouse in Lower Manhattan, also documents something else: a contentious period in the city when the police engaged in surveillance, much of it covert, that was designed to keep tabs on political activities and was later restricted as part of a court settlement.

To Thomas A. Reppetto, an author and police historian, the very fact of the exhibit — “Unlikely Historians: Materials Collected by NYPD Surveillance Teams, 1960–1975” — is evidence of how much times have changed. Years ago, he said, a city agency would have been hard-pressed to stage an exhibition that resurrected the memory of provocative police practices.

“The police would not have wanted to do it,” Mr. Reppetto said. “The police would never have agreed to it, and if the police didn’t agree, it wouldn’t be done.”

Mr. Reppetto is no fan of the exhibit, suggesting that making intelligence material public can often reveal sensitive tactics. But curators say they received no objections from the Police Department or City Hall while they were putting the exhibit together. In fact, among the visitors to the exhibit has been Police Commissioner James P. O’Neill. (A police spokesman did not respond to a question seeking the commissioner’s thoughts on the images.)

The show, which opened last month, includes 30 photographs and seven film segments created while the police Photo Unit was working with investigative bureaus like the now-defunct Special Services Division, whose members monitored groups they deemed to be dangerous or subversive.

The path toward the exhibition began, the records department officials say, with a phone call in 2011 from the police, who were looking for advice on how to dispose of old nitrate film, which can be combustible. A curator at the records agency, Michael Lorenzini, who is now the deputy director of the Municipal Archives, went to visit a damp basement inside Police Headquarters where he found dozens of boxes of photo negatives and glass plates containing about 150,000 images from 1897 to 1975.

It was an archivist’s dream: mug shots, photographs of murder scenes and documentation of police ceremonies in addition to the surveillance material, all of it with historic merit. The crew of archivists began cataloging the photographs, using police records, including logbooks, to figure out what the pictures depicted. In addition, the records department discovered a number of reels of film shot between 1960 and 1980. The agency is planning to raise money to digitize the film and so far has examined only a handful of reels.

“We know there’s gold in there but it’s kind of hidden,” said Quinn Bolewicki, an archivist who worked on the cataloging.

The curators decided that among the most interesting materials were the surveillance images and footage from the 1960s and 1970s, an archive that city curators view as one of the most expansive visual records of political and social movements in the United States from that era. Sometimes the image-gathering was clandestine, performed by plainclothes officers who carried still cameras and circulated quietly through the crowds. Other times the monitoring efforts were more open, with officers setting up large movie-style cameras next to police vehicles.

A visit to the gallery carries one back to an impassioned and divisive era. Here are images of people gathered in Central Park in 1967 for the Spring Mobilization Committee March, a large protest against the Vietnam War. In one, a young man in a dark coat holds aloft a burning draft card. Another shows counterdemonstrators as they converge inside the park. One man carries a sign that reads in part “Let’s Bomb Hanoi.”

Some of the police surveillance was curtailed by a lawsuit that ended in 1985 with a federal consent decree that restricted how the police were permitted to investigate political activity. The suit, Handschu v. Special Services Division, asserted that undercover officers had violated the civil rights of members of groups like the Black Panther Party and Veterans and Reservists Against the War in Vietnam by spying on, infiltrating and disrupting their activities. As part of the consent decree, the police agreed they would not investigate political groups that had not been linked to criminal activity.

One of the lawyers who filed the suit, Martin R. Stolar, and one of the plaintiffs, Joe Sucher, have toured the exhibition. Mr. Sucher was also one of four New York University students who made the documentary “Red Squad,” a film that detailed efforts to expose police surveillance at political events and was screened for a week in 1972 at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Mr. Sucher said it was interesting to review images from events he had attended and had, indeed, photographed himself.

“It had a familiar feeling, albeit from a different perspective,” he said. “We shot some of those same demonstrations looking for the police who were shooting the demonstrations from the other side.”

Anthony V. Bouza, a former police lieutenant who served in special services between 1957 and 1965, said he found it remarkable that the city had organized such a show, given what he called the Police Department investigative divisions’ “passion for secrecy, generally.”

Mr. Bouza, who wrote the book “Police Intelligence: The Operations of an Investigative Unit” (1976), credited the special services officers and their surveillance work with protecting the public from potentially dangerous activities by groups like the American Nazi party. But he said the police had also overstepped their bounds by investigating antiwar groups like Women Strike for Peace. Mr. Bouza said he applauded efforts to explore what he called the “complex mix of positives and negatives” that marks the unit’s history.

The court-ordered restrictions on police surveillance have evolved over the years, often in response to events. After 9/11 and the destruction and death it brought, the standards were relaxed by a federal judge overseeing the Handschu case. This year the Police Department agreed to greater oversight of its intelligence operations to settle a lawsuit brought by Muslims who said they were being spied on because of their religion.

The exhibition itself does not present any commentary on the police activities. The wall text is neutral and reports that since 1904, the Police Department has conducted surveillance of people and infiltrated groups “perceived as enemies of the status quo.”

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/09/arts/how-police-surveillance-units-became-unlikely-historians.html

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit