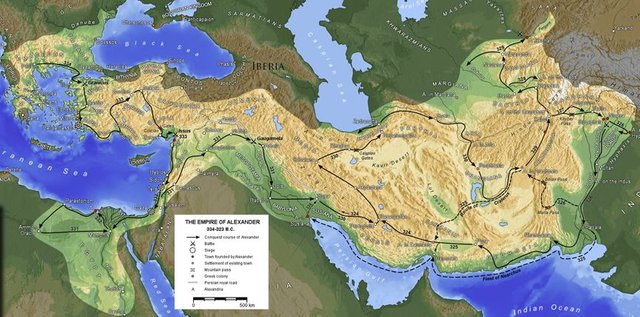

For his part, Darius used the time to gather new allies. This time he wanted to face his opponent personally. Alexander, who had not only made friends by his aggressive policies, suddenly saw himself encircled by enemies when the Great King succeeded in finding support and allies in the Greek mainland for the fight against him. More menacing, however, was that Darius had put together a new army. The vast resources of his empire allowed him to more than make up for the losses of the first battle.

Alexander decided to beat Darius first, before turning to the enemies in his back. However, the road to the Great King was not without its dangers: The Cilician Gate, a bottleneck in the Taurus Mountains, was the only viable route to Darius. Four gunmen had space here between the steep rock walls, a perfect condition for an ambush or an insurmountable defensive line. But again the Persians refrained from stopping the enemy. They could easily have used the same strategy here, with the 300 Spartans in the battle of Thermopylae in 480 BC. Thousands of Persians had stopped. But either Darius did not recognize the strategic importance of the passport or he still underestimated the threat.

In any case, the Greeks managed to rout the few Persian defenders and cross the bottleneck. Alexander himself was surprised when he discovered afterwards how easy it would have been to stop him at the Cilician Gate. Incidentally, we owe the detailed knowledge of the battles of Alexander to the Greco-Roman historian Arrianus, who in the 2nd century AD summed up several eyewitness accounts and thus received posterity.

The two opponents were now, in November 333 BC. Not far from each other. Alexander hurried east towards the Gulf of Issus, where he supposed Darius. The Amanos Mountains bound the gulf on the east side and separated it from the Persians, who moved from the north to the mountain range. Without reliable remote reconnaissance, both commanders could only guess what the enemy would do next. Basically, both strategists had the opportunity to wait until the enemy came, or drag them across the mountains. For the latter two passes were available: the Löwen Pass in the north and the Bailan Pass in the south.

Both Alexander and Darius decided on the offensive. The Greeks occupied the Bailan Pass and Alexander moved his entire army south. Darius, however, crossed the mountains over the still free lion pass. The result of these troop shifts surprised both commanders. The Great King had to realize that the Macedonians had moved south, while Alexander realized that the Persians were suddenly on the same side of the mountain as he was.