One night of March on the beach side, in the enveloping warmth and mad chaos of the carnival, I had a chat with a street vendor. That was in Salvador da Bahia, on the northern coast of Brazil. Almost yelling to cover the electronics’ beat, she asked me what I thought of Salvador’s carnival; and I had to confess my disappointment. Naïve or ignorant, I had left Rio de Janeiro a few days before the world’s most famous carnival, longing for the wild soul of Bahia, Brazil’s northern coast. Longing for the carnival of the streets, of the people; for the fruits of Africa and Europe’s couplings, the bewitching rhythms and the Candomblé gods; for Brazil’s “cultural cannibalism”, as the poet Oswald de Andrade said.

I found… the ubiquitous cash machine, the ubiquitous greens. I found a globalized, mercantile event, a Disneylandish show of the legacies of the African kings. When I confessed it to the Bahiana woman, in my shitty Portuguese, she didn’t look surprised. She said with scintillating eyes: “You have to write of it. People need to know; you should write about it.” She had never seen me before, she couldn’t possibly know that, strangely enough, I did write. So I write of it. I write to say Salvador is a shameful lie; and I write to say I loved it madly anyways.

Salvador da Bahia. If you think what you’ve heard of Brazil, sensual, hectic, miserable Brazil – is exaggerated, romanticized… Close your eyes and multiply. São Salvador de todos os santos e todos os pecados; the city of all saints and sins. The elderly cripples sleeping on the stairs of the colonial churches; virgin beaches, tireless drums and crackhead kids. Fairy tale pastel houses, and the mold eating away their stucco friezes.

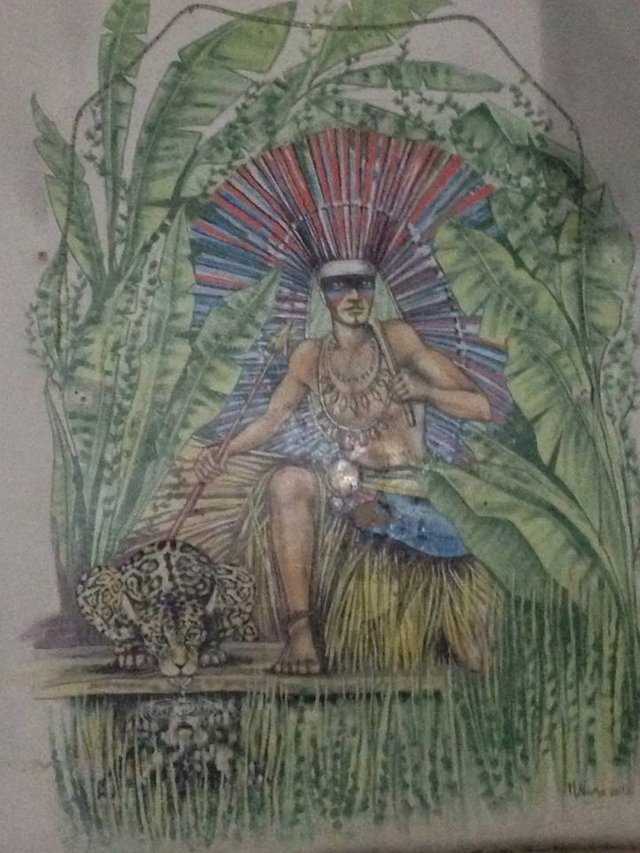

The tale starts in 1536, when Francisco Pereira Coutinho claims the land for Juan II, king of Portugal. The tale starts, with all of Brazil bloodthirsty beauty, with a native tribe feasting on the cruel Portuguese captain who tried to subdue them. Brazil and cannibalism. Salvador is founded; soon crowds of slaves arrive from Africa, from Benin and Sudan especially, and the city thrives on the sugar trade. Two centuries go by before, in 1763, Rio de Janeiro replaces Salvador as Brazil’s capital.

Today, Salvador is about three millions inhabitants strong, the third population in the country. Its murder rate is one of the highest in the world, and it is exemplary of Brazil’s vertiginous social inequities (the HDI oscillates between Norway’s and Tajikistan’s, from one neighborhood to the next). It is, however, the second most popular holiday spot in Brazil. São Salvador da Bahia, Capital da Alegria… the capital of joy.

Imagine a harbour of blue, oh so blue waters, and, towering over it, a colossal wall of lush green strewn with all-coloured colonial houses. On top, o Pelourinho, the city’s historical centre; down, a cidade baixa, the low town, bordered with beaches of jagged rocks, as beautiful and wild as Rio’s are worldly. In between, huge and carving this wall of green foliage from sky to sea, the Lacerda elevator, which has been carrying the Bahianos for 140 years.

O Pelourinho… Literally, “the little pillory”, for there, century after century, were chastised the slaves. A small neighbourhood, filled with beauty and misery, romanticism and sexual tourism. Something to do with New Orleans, with Havana, with all the gorgeous and outdated colonial cities running along America. The paved streets, the thousand and one pastel shades of the facades, the delicate stucco chiselled like whipped cream. The dark-skinned elderly peddlers, the smell of fried food, the thousands of supposedly “typical” souvenirs everywhere flaunted. Music, day and night, tirelessly, and the absurd Capoeira dancers, swirling weightlessly to the berimbaus’ melody. The ones who dance for Deus and the ones who dance for dollars. For the slave district now belongs to tourist money; the secret, sacred dance of those same slaves, is now a show for the gringo to see.

Roaming Pelourinho’s beautiful streets the spell is bittersweet; alongside tourists walk dozens of barefoot kids and elders, begging for crack pipe money. In the 90s the district, declared World Heritage, was restored and its black inhabitants thrown out. Alone matters the pastel front the tourists see; the rot eats away the footings secretly. A few meters away lies a mud and concrete favela; when the kids see me, too blonde to be there, they forget their football and run after me. On the other side, wandering another street, a hellish, post-apocalyptic neighborhood lies, lush ferns overflowing from the shallow window frames of the cracked pink, purple, blue and green facades.

Anywhere and always, beautiful faces. Salvador is a Roma Negra, the city, in the whole world, with the highest percentage of black blood outside Africa. And nowhere else, really, has the power of the European-African blend appeared to me more blatant, or more seductive… than in the chiselled features and honey cheeks of Bahia’s beauties. This, whether in the historic centre favelas or in the delicious, fashionable clubs of Rio Vermelho, the beach side neighborhood in the southeast of the city.

Handsome, half-naked always in the smothering heat, and looking for pleasure tirelessly. For what is Salvador’s carnival, “the biggest street party in the world”, if not a week of heathen cult to the three gods of pleasure, Music, Sex and Booze? In each one of the three carnival “routes”, hundreds of Bahianos, the self-called “Gandhis”, easily spotted for their blue and white gown, for the turban hiding their black curls, bargain one of their countless necklaces for a kiss. They wears dozens and dozens of necklaces of plastic pearls, and the game, literally, is to kiss as many women as remain necklaces.

They hunt in Batatinha, the Pelourinho route, the one of the Candomblé dances, of the kids’ bands and the reggae concerts. They hunt on the churches’ stairs, next to the spicy shrimp peddlers. They hunt on the Dodo route, along the beaches of dark jagged rocks, from the lighthouse, Farol da Barra, to the beach, Praia da Ondina. They hunt in Campo Grande, on Osmar, the original route that started in 1950. The most authentic and the most dangerous, the one that smells like piss, honestly.

For in Salvador are two carnivals, and those are two different worlds. Just as the colonial houses crumble behind their whipped cream fronts, Bahia’s carnival, though as wondrous and grotesque and orgiastic, though as pagan or better yet, syncretic, as its European ancestor; Bahia’s carnival is losing its core. In medieval Europe, the days before Lent were a time for impertinence. It was a time for the peasant to dress up as the earl, for the pagan to laugh at the priest, for the beggar to shag the lady, maybe. It was about drinking and shagging, yes, but it was about freedom. It was about messing up the law, stirring the castes; it was about bright-painted masks hiding the ones we wear daily.

And yes, Salvador’s carnival is a beautiful legacy. Its mad music is syncretic, a hymn to the African gods; the priest and the pagan do dance to the beat; but the castes are established, most definitely. The trios electricos, the trucks, loaded with huge speakers, that carry the samba bands across the city, are isolated from the crowds by ropes and guards. On the right side of the rope, around the band, is o bloco. On either side of the street, huge stands. To have access to bloco or stand, one has to wear the abadá shirt, the ridiculously expensive carnival uniform that distinguishes the VIP. So much so for disguise, so much so for messing with hierarchy.

Bahia’s carnival is a tragic farce; it spellbound me all the same. For there are two carnivals, and the one on the wrong side of the rope is the one I loved madly. To wait for the guard’s first second of absentmindedness and sneak in, not even because it is funnier inside the bloco, but because it is fun to get kicked out and try again. To dance, for hours on end, to the mesmerizing beat of dozens of drums, drums that the Rastas with coloured pearls in their hair throw in the air in a mystic, tribal prayer. To vibrate, through each and every nerve, to the samba and axé of Timbalada, Carlinhos Brown and Olodum; and, white as one may be, to feel the ancient roar of Africa swelling up inside one’s belly. To meet friends at the lighthouse, Farol da Barra, at twilight, and, jumping to the drums in the waves – for the foam’s back and fo and the beat tune up; to get drunk on cheap beer and raking golden light.

São Salvador da Bahia… is Brazil: joyful and miserable, filled with music and violence, colour and anger. A cash machine and a crack hole. And I can’t seem to forget this fifteen years old kid, the piercings on his baby face, his copper skin, his blond curls and his impish smile. Two necklaces were tangled on his chest: an ostentatious cross and a Playboy’s bunny. Brazil’s saints and sins, most definitely.

Congratulations @dianedurden! You have received a personal award!

Click on the badge to view your Board of Honor.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Congratulations @dianedurden! You received a personal award!

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

Vote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit