The sun is out and mosquitoes form small clouds over the path ahead of me, just where I will want to stand to take my next picture. As I try to focus my camera on Stalin’s moustache and disperse the insects at the same time, stout Russian voices break into song and I just can’t help myself any longer. I start to laugh. I am in a Lithuanian theme park called the Grutas Park and it has to be the strangest place I have ever been.

The Grutas Park is southern Lithuania’s biggest tourist attraction and has been open since 2001. The Park was the brainchild of mushroom entrepreneur Viliumas Malinauskas, who bought all the park’s sculptures in the decade after the country became independent in 1991. He realized that after the downfall of Communism and the break up of the Soviet Union, all the statues from this era of Lithuanian history would need a home before they were destroyed and so the Grutas Park came into existence. My guide wouldn’t verify the ugly rumour that Malinauskas had wanted to take people around the park in a train pulling cattle trucks, similar to those used to export many post-WWII Lithuanians to the gulags in Siberia.

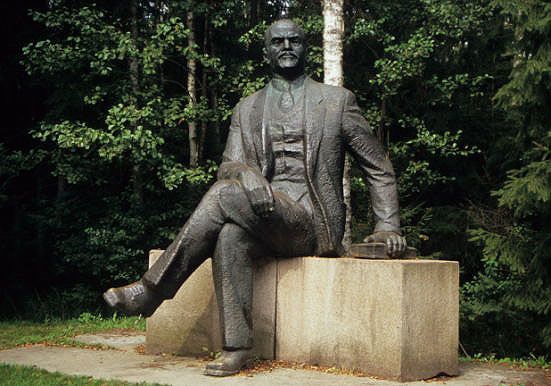

As I continue to walk down the path, past the grey statue of Vladimir Ilyich Lenin on my left hand side, the Soviet marching music is still playing from loudspeakers attached to imitation Gulag watchtowers in the forest by a small stream on my right. Each statue has an English translation of where the statue stood in the Communist era; for example, the lovely Stalin statue stood outside the train station in Vilnius, which must have cheered commuters no end as they shuffled to their work. There are no statues or pictures of Trotsky, and not all the statues are of Stalin, Marx, and Lenin. Felix Dzerzhinsky, founder of the KGBs forerunner the Cheka, is present looking very sleek and sinister in a long cape. There are statues of Lithuanian heroes such as 20-year old freedom fighter Maryte Melnikaite who was shot by the Nazis in 1943 and of the Four Communards, the underground communist leaders who were shot in 1926 in Kaunas, Lithuania’s second city.

After a tour of the statues that took about an hour, I went to the canteen, where there was a choice between a lengthy, ‘normal’ menu and a much shorter ‘Nostalgia’ menu, specializing in Soviet style cuisine. I decide to enter the spirit of the park and select my lunch from one of the three nostalgia dishes on offer. The picture of the “Goodbye Youth” chop indicated to me that there was no actual meat on the chop – that it was just bone with some marrow attached. “Hello Hunger” would have been a better name. I was left with a straight choice between the single sausage draped elegantly over the side of a metal dish or “Sprat Done The Russian Way”. The sprat was garnished with a single ring of raw onion and the ‘Russian Way’ was to have a glass of vodka with the sprat. Just to complete the theme, pictures of Lenin and Stalin adorned the glass. I had the sausage. It was delicious, but was slightly too pink in colour for my liking.

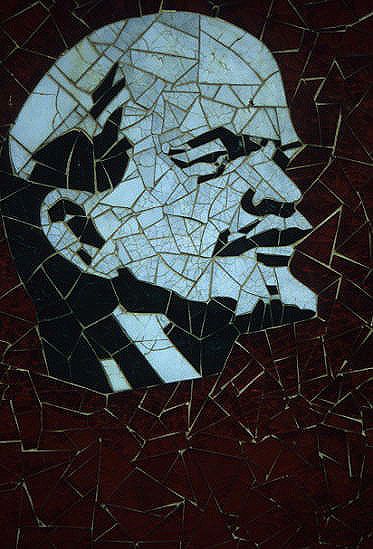

The museum has an eclectic collection of Communist memorabilia including “Vote for me” posters from a time when it was obviously illegal for those seeking your vote to look happy when they posed for the pictures that appeared on election material. The military men looked especially stern. This contrasted sharply with a painting of Joe Stalin on the opposite wall. Looking every inch the benevolent, cuddly uncle in a dressing gown, Stalin was smoking a pipe and reading a book in his library. He looked very calm and I had to remind myself that for every book behind him in the painting, Stalin had around 1.5 million people murdered. Stalin’s popularity was such that when he died, almost all the statues of him were immediately destroyed and replaced by ones of Lenin, who had died nearly thirty years earlier. The rule was: The bigger the city, the bigger the Lenin. The statue of Lenin in Vilnius was six metres high, whereas in Kaunas, Lenin was only 5.8 metres high.

The art gallery contained a huge selection of art works that defined Social Realism: dreadful tapestries of parallel and perpendicular coloured lines that would only be improved if your cat sharpened its claws on them; muscular and angular statues of Soviet heroes; and for me the piece de resistance, hanging on the wall, in a wooden frame, was a three-dimensional ceramic swine herder, whose piglets were fat, pink, and almost ready to be fed to the masses. Once seen, never forgotten. Perhaps that’s where my sausage came from.

Beneath the humour there is a method at work. Preserving these mementoes of the dark Communist past keeps those times alive for future generations to see and ask what they were about, ensuring that the spectre of Soviet domination never returns. I thought of the Armoury in the Kremlin in Moscow, which Lenin insisted should be preserved so that its riches could be seen by all and would then be a reminder of what the Revolution overthrew.