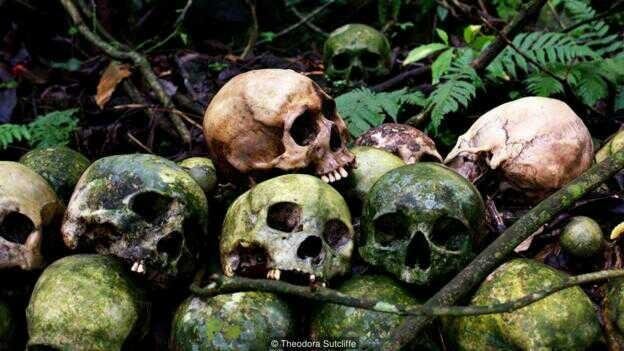

The villagers of Bali Aga leave those who die to rot in the open air, under the magic, ancient trees that are said to stop the corpses from the smell.

"My cousin is there," says my guide, Ketut Blen, pointing to the skulls and packets underneath the palm and bamboo skeletons. "But I did not feel anything when I saw it."

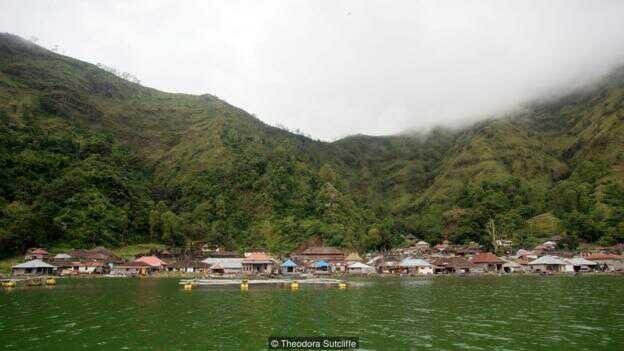

The cemetery in Trunyan, Bali, where villagers wade through bodies with canoes to rot in the open air, is a remote place. Sheltered by steep slopes and forests, it lies on the banks of a vast upland crater lake, with a short boat trip from its mother village. And, on an island where most Balinese Hindus cremate their deaths, Trunyan is unique.

The Bali Aga people live in remote and remote villages in northeastern Bali.

The Blen Bali Aga people, who live in isolated and remote villages, especially in northeastern Bali, are some of the island's oldest inhabitants: Trunyan comes from at least 911 CE. Like most Balinese, Bali Aga follows the eccentric Bali of Hinduism, but every village group, like the village group headed by Trunyan, also has its own religious rituals and beliefs.

In Tenganan, Bali's most famous village of Aga, it means young women who can marry the bamboo umbilical cord and weave magic tricks. In Trunyan, it means ritual whipping with rattan shoots and exposing dead people to rot in the open air.

There are 11 cages of palm and bamboo arched at the cemetery.

There are actually two cemeteries in Trunyan, Blen explained, with this one of life's journey counts as complete.

"Everyone here had been married when they died," he said. "People who die before they are married, or drown in the lake, we put in the earth."

Religion in Trunyan is even more dense with animism than most Balinese Hinduism. The village, dominated by a grand temple 11 pagodas mirror the 11 corpses exposed in the cemetery, has a perilous location. It perches below an active volcano on the shores of a choppy crater lake, imperilled by the twin natural dangers of fire and water.

Arriving at Trunyan.

The volcano, Mount Batur, has shaped death and life here for centuries.

"Here we have a volcano," Blen explained. "So it's impossible to burn people. It could cause problems with volcanoes. "

Initially out of fear of raging volcanoes - now identified as the Hindu god Brahma - the dead are left to rot. The number 11 has a rich meaning in Hinduism, so there are only 11 curved cages on the ground and bamboo in the cemetery; After all filled, the villagers move the oldest remnants into an open ossuary.

That is if there are any remnants left to move. Often, the bones just disappeared - the victims, I assume, from monkeys shouting in the woods and partying with the remaining food for gods and dead bodies.

Ossuary opens.

However, for all the garbage and dirt that fill the graves - the human thighs are casually thrown beside the ancient flip-flop amid the empty dish clutter - the place has a strange calmness. Surprisingly, there is no smell of death. The corpses, sheltered by bright umbrellas and dressed in their favorite outfits, were peaceful. And the look of the skull on the ossuary seemed calm, their journey over and the spirits flown.

The latest addition to the cemetery is the village priest, or mangku, who died 26 days before my visit; Blen's cousin was there for months. Because corpses can only be brought to graves and adjacent temples on good days, and families have to raise money for funerals, some corpses stay home for days or weeks before. Villagers use formaldehyde to stop their loved ones decompose during long wait.

Once the enclosure is filled, the villagers move the oldest remnants into the open ossuary.

The village on the Puser hillside, part of the Trunyan cluster, also has an open cemetery. As our boat passed, the remains of the rotting corpses were visible at a depth of 100m above the water.

But when we arrived at Trunyan's cemetery, there was no smell at all. I looked through the lontar cage into the empty eye of a man whose black flesh still stuck to his skull, and only picked up the faintest smell.

There is more than formaldehyde for the lost odor, it seems. The towering, matted, mossy tree that looks like an ancient banyan tree dominates the open cemetery. Locals believe that the tree, called Taru Menyan, or "fragrant tree", defeats the stench.

The bodies were sheltered by bright umbrellas.

“This tree is magic,” explained Blen's friend, Ketut Darmayasa. “At home the bodies would smell. Here, it's only because of the tree.”

It's not just the death ritual and the magic tree that makes this lakeside fishing village unusual. The entire village still gathers to make communal decisions at the bale agung, a cluster of open-air platforms that form the heart of the three-tiered village. And once a year, around October, the young men dress up in elaborate costumes of fringed banana leaf and brandish rattan shoot whips in a ritual dance called Brutuk. Its aim? To sanctify the temple, thus keeping the village and villagers safe.

But it's the cemetery, with its strange serenity, that defines Trunyan. And there, surrounded by reminders of the mortality we all share and the death that will come to all of us, I asked Blen how he could look at the decaying remains of the cousin he had loved and not feel grief.

The decaying remains of a loved one.

He and Darmayasa discussed a while in Balinese. “He is only sad at home,” Darmayasa said. “[In the cemetery] he doesn't feel any grief.”

“Why” I asked again.

“Because it's our culture,” Darmayasa said simply.

For in Trunyan, as everywhere, both death and grief are cultural acts: it's just more obvious here.

A view of Trunyan's grand temple.

Wow beautiful 😍😍

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

please help support me, because with your support make me more spirit in work

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit