THE STORY OF TURKISH FOOD: A PROLOGUE

For those who travel in culinary pursuits, the Turkish Cuisine is a very curious one. The variety of dishes that make up the Cuisine, the ways they all come together in feast-like meals, and the evident intricacy of each craft offer enough material for life-long study and enjoyment. It is not easy to discern a basic element or a single dominant feature, like the Italian "pasta" or the French "sauce". Whether in a humble home, at a famous restaurant, or at a dinner in a Bey's mansion, familiar patterns of this rich and diverse Cuisine are always present. It is a rare art which satisfies your senses while reconfirming the higher order of society, community and culture.

A practical-minded child watching Mother cook "cabbage dolma" on a lazy, gray winter day is bound to wonder: who on earth discovered this peculiar combination of sautéed rice, pine-nuts, currants, spices, herbs and all tightly wrapped in translucent leaves of cabbage all exactly half an inch thick and stacked-up on an oval serving plate decorated with lemon wedges? How was it possible to transform this humble vegetable to such heights of fashion and delicacy with so few additional ingredients? And, how can such a yummy dish possibly also be good for one?

The modern mind, in a moment of contemplation, has similar thoughts upon entering a modest sweets shop in Turkey where "baklava" is the generic cousin of a dozen or so sophisticated sweet pastries with names like: twisted turban, sultan, saray (palace), lady's navel, nightingale's nest... The same experience awaits you at a "muhallebi" (pudding shop) with a dozen different types of milk puddings.

One can only conclude that the evolution of this glorious Cuisine was not an accident. Similar to other grand Cuisines of the world, it is a result of the combination of three key elements. A nurturing environment is irreplaceable. Turkey is known for an abundance and diversity of foodstuff due to its rich flora, fauna and regional differentiation. And the legacy of an Imperial Kitchen is inescapable. Hundreds of cooks specializing in different types of dishes, all eager to please the royal palate, no doubt had their influence in perfecting the Cuisine as we know it today. The Palace Kitchen, supported by a complex social organization, a vibrant urban life, specialization of labor, trade, and total control of the Spice Road, reflected the culmination of wealth and the flourishing of culture in the capital of a mighty Empire. And the influence of the longevity of social organization should not be taken lightly either. The Turkish State of Anatolia is a millennium old and so, naturally, is the Cuisine. Time is of the essence; as Ibn'i Haldun wrote, "the religion of the King, in time, becomes that of the People", which also holds for the King's food. Thus, the reign of the Ottoman Dynasty during 600 years, and a seamless cultural transition into the present day of modern Turkey, led to the evolution of a grand Cuisine through differentiation, refinement and perfection of dishes, as well as their sequence and combination of the meals.

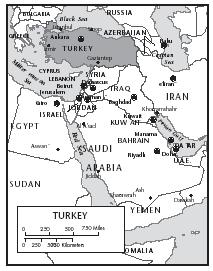

It is quite rare that all the three conditions above are met, as they are in the French, the Chinese and the Turkish Cuisine. The Turkish Cuisine has the extra privilege of being at the cross-roads of the Far-East and the Mediterranean, which mirrors a long and complex history of Turkish migration from the steppes of Central Asia (where they mingled with the Chinese) to Europe (where they exerted influence all the way to Vienna).

All these unique characteristics and history have bestowed upon the Turkish Cuisine a rich and varied number of dishes, which can be prepared and combined with other dishes in meals of almost infinite variety, but always in a non-arbitrary way. This led to a Cuisine that is open to improvisation through development of regional styles, while retaining its deep structure, as all great works of art do. The Cuisine is also an integral aspect of culture. It is a part of the rituals of everyday life events. It reflects spirituality, in forms that are specific to it, through symbolism and practice.

Anyone who visits Turkey or has had a meal in a Turkish home, regardless of the success of the particular cook, is sure to notice how unique the Cuisine is. Our intention here is to help the uninitiated to enjoy Turkish food by achieving a higher level of understanding of the repertoire of dishes, related cultural practices and their spiritual meaning.

A Nurturing Environment

Early historical documents show that the basic structure of the Turkish Cuisine was already established during the Nomadic Period and in the first settled Turkish States of Asia. Culinary attitudes towards meat, dairy, vegetables and grains that characterized this early period still make up the core of Turkish Cuisine . Turks cultivated wheat and used it liberally in several types of leavened and unleavened breads baked in clay ovens, on the griddle, or buried in ember. "Manti" (dumpling), and "bugra" (attributed to Bugra Khan of Turkestan, the ancestor of "börek" or dough with fillings), were already among the much-coveted dishes at this time. Stuffing the pasta, as well as all kinds of vegetables, was also common practice, and still is, as evidenced by dozens of different types of "dolma". Skewering meat as well as other ways of grilling, later known to us as varieties of "kebap" and dairy products such as cheeses and yogurt were convenient and staple foods of the pastoral Turks. They introduced these attitudes and practices to Anatolia in the 11th century. In return they were introduced to rice, the fruits and the vegetables native to the Region, and the hundreds varieties of fish in the three seas surrounding the Anatolian Peninsula. These new and wonderful ingredients were assimilated into the basic Cuisine in the millennia that followed.

Anatolia is a Region coined as the "bread basket of the world". Turkey, even now, is one of the seven countries in the world which produces enough food to feed everyone and then some to export. The Turkish landscape encompasses such a wide variety of geographic zones, that for every two to four hours of driving, you will find yourself in a different zone with all the accompanying changes in scenery, temperature, altitude, humidity, vegetation and weather conditions. The Turkish landscape has the combined characteristics of the three old continents of the world : Europe, Africa and Asia, and an ecological diversity surpassing any other place along the 40th latitude. Thus, the diversity of the Cuisine has come to reflect that of the landscape and its regional variations.

In the Eastern Region, you will encounter the rugged, snow-capped mountains where the winters are long and cold, and the highlands where the spring season with its rich wild flowers and rushing creeks extends into the long and cool summer. Livestock farming is prevalent. Butter, yogurt, cheeses, honey, meat and cereals are the local food. Long winters are best endured with the help of yogurt soup and meatballs flavored with aromatic herbs found in the mountains, and endless servings of tea.

The heartland is dry steppes with rolling hills, endless stretches of wheat fields and barren bedrock that takes on the most incredible shades of gold, violet, cool and warm grays, as the sun travels the sky. Ancient cities were located on the trade routes with lush cultivated orchards and gardens. Among these, Konya, the capital of the Seljuk Empire (the first Turkish State in Anatolia), distinguished itself as the center of a culture that attracted scholars, mystics, and poets from throughout the world during the 13th century. The lavish Cuisine that is enjoyed in Konya today, with its clay-oven (tandir) kebaps, böreks, mcat and vegetable dishes and helva desserts, dates back to the feasts given by Sultan Alaaddin Keykubad in 1237 A.D.

Towards the west, one eventually reaches warm, fertile valleys between cultivated mountainsides, and the lace-like shores of the Aegean where nature is friendly and life has always been easy. Fruits and vegetables of all kinds are abundant, including the best of all sea food! Here, olive oil becomes a staple and is used both in hot and cold dishes.

The temperature zone of the Black Sea Coast, well-protected by the high Caucasian Mountains, is abundant with hazelnuts, corn and tea. The Black Sea people are fishermen and identify themselves with their ecological companion, the shimmering "hamsi", a small fish similar to anchovy. There are at least forty different dishes made with hamsi! Many poems, anecdotes and folk dances are inspired by this delicious fish.

The south-eastern part of Turkey is hot and desert-like and offers the greatest variety of kebabs and sweet pastries. Dishes here are more spicy compared to all other regions, possibly to retard spoilage in hot weather, or as the natives say, to equalize the heat inside the body to that of the outside!

The culinary centre of the country is the Marmara Region which includes Thrace, with Istanbul as its Queen City. This temperate, fertile Region boasts a wide variety of fruits, vegetables, and the most delicately flavored lamb. The variety of fish that travel the Bosphorus surpasses those in other seas.

Bolu, a city on the mountains, supplied the greatest cooks for the Sultan's Palace, and even now, the best chefs in the country come from Bolu. Istanbul, of course, has been the epicenter of the Cuisine, and an understanding of Turkish Cuisine will never be complete without a survey of the Sultan's kitchen...

Kitchen of the Imperial Palace

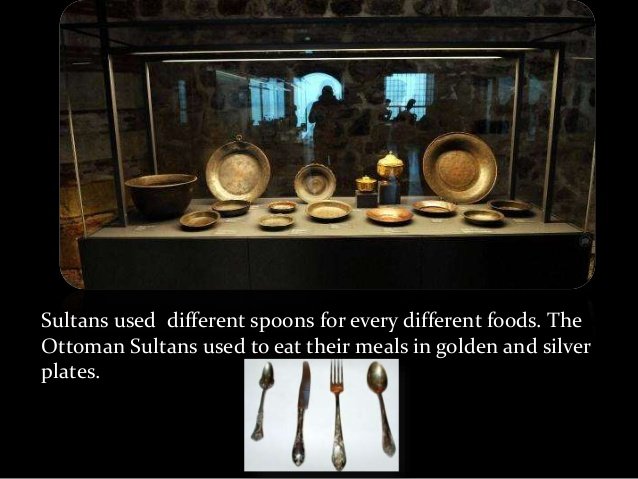

The importance of culinary art for the Ottoman Sultans is evident to every visitor of Topkapi Palace. The huge kitchens were housed in several buildings under ten domes. By the 17th century, some thirteen hundred kitchen staff were housed in the Palace. Hundreds of cooks, specializing in different categories of dishes such as soups, pilafs, kebaps, vegetables, fish, breads, pastries, candy and helva, syrup and jams and beverages, fed as much as ten thousand people a day, and in addition, sent trays of food to others in the City as a royal favor.

The importance of food has been also evident in the structure of the Ottoman military elite, the Janissaries. The commanders of the main divisions were known as the Soupmen, other high ranking officers were the Chief Cook, Scullion, Baker, and Pancake Maker, though their function had little to do with these titles. The huge cauldron used to make pilaf had a special symbolic significance for the Janissaries, as the central focus of each division. The kitchen was also the centre of politics, for whenever the Janissaries demanded a change in the Sultan's Cabinet, or the head of a grand vizier, they would overturn their pilaf cauldron. "Overturning the cauldron," is an expression still used today to indicate a rebellion in the ranks.

It was in this environment that hundreds of the Sultans' chefs, who dedicated their lives to their profession, developed and perfected the dishes of the Turkish Cuisine, which was then adopted by the kitchens of the provinces ranging from the Balkans to Southern Russia, reaching Northern Africa. Istanbul was the capital of the world and had all the prestige, so that its ways were imitated. At the same time, it was supported by an enormous organization and infrastructure which enabled all the treasures of the world to flow into it. The provinces of the vast Empire were integrated by a system of trade routes with refreshing caravanserais for the weary merchants and security forces. The Spice Road, the most important factor in culinary history, was under the full control of the Sultan. Only the best ingredients were allowed to be traded under the strict standards established by the courts.

Guilds played an important role in the development and sustenance of the Cuisine. These included the hunters, the fishermen, the cooks, the kebab cooks, bakers, butchers, cheese makers and yogurt merchants, pastry chefs, pickle makers and sausage merchants. All of the principal trades were believed to be sacred, and each guild traced its patronage to the Prophets and Saints. The guilds prevailed in pricing and quality control. They displayed their products and talents in spectacular floats driven through Istanbul streets during special occasions, such as the circumcision festivities for the Crown Prince or religious holidays.

Following the example of the Palace, all of the grand Ottoman houses boasted elaborate kitchens and competed in preparing feasts for each other as well as the general public. In fact, in each neighbourhood, at least one household would open its doors to anyone who happened to stop by for dinner during the holy month of Ramadan, or during other festive occasions. And this is how the traditional Cuisine evolved and spread, even to the most modest corners of the country.

A Repertory Of Food At The Great - Good Places

A survey of types dishes according to their ingredients, may be helpful to explain the basic structure of the Turkish Cuisine. Otherwise it may appear to have an overwhelming variety of dishes, each with a unique combination of ingredients, way of preparation and presentation. All dishes can be conveniently categorized into: grain-based, grilled meats, vegetables, fish and sea-food, desserts and beverages.

Before describing each of these categories, some general comments are necessary. The foundation of the Cuisine is based on grains (rice and wheat) and vegetables. Each category of dishes contains only one or two types of main ingredients. Turks are purists in their culinary taste; the dishes are supposed to bring out the flavour of the main ingredient rather than hiding it behind sauces or spices. Thus, the eggplant should taste like eggplant, lamb like lamb, pumpkin like pumpkin. Contrary to the prevalent Western impression of Turkish food , spices and herbs are used with zucchini, parsley with eggplant, a few cloves of garlic has its place in some cold vegetable dishes, cumin is sprinkled over red lentil soup or mixed in ground meat when making "köfte". Lemon and yogurt are used to complement both meat and vegetable dishes, to balance the taste of olive oil or meat. Most desserts and fruit dishes do not call for any spices. So their flavours are refined and subtle.

There are major classes of meatless dishes. When meat is used, it is used sparingly. Even with the meat kebabs, the "pide" or the flat bread occupies the largest part of the portion along with vegetables or yogurt. The Turkish Cuisine also boasts a variety of authentic contributions in the desserts and beverage categories.

For the Turks, the setting is as important as the food itself. Therefore, food-related places need to be surveyed, as well as the dishes and the eating-protocol. Among the "great-good places" where you can find the ingredients for the Cuisine, are the weekly neighbourhood markets- "pazar", and the permanent markets. The most famous one of the latter type is the Spice Market in Istanbul. This is a place where every conceivable type of food item can be found, as it has always been since pre-Ottoman times. This is a truly exotic place, with hundreds of scents rising from stalls located within an ancient domed building, which was the terminal for the Spice Road. More modest markets can be found in every city centre, with permanent stalls of fish and vegetables.

The weekly markets are where sleepy neighbourhoods come to life, with the villagers setting up their stalls before dawn at a designated area, to sell their products. These days, handicrafts, textiles, glassware and other household items are also among the displays at the most affordable prices. What makes these places unique is the cacophony of sights, smells, sounds and activity, as well as the high quality of fresh food, which can only be obtained in the pazar. There is a lot of haggling and jostling, as people make their way through the narrow isles while the vendors compete for attention. One way to purify body and soul would be to rent an inexpensive flat by the seaside for a month every year, and live on fresh fruit and vegetables from the "pazar". However, since the more likely scenario will be restaurant-hopping, here are some tips to learn the proper terminology so that you can navigate through both, the Cuisine (just in case you get the urge to cook a la Turca), and the streets of Turkish cities, where it is just as important to locate the eating places as the museums and the archaeological wonders.

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

http://www.turkishculture.org/culinary-arts/cuisine/turkish-food-302.htm?type=1

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit