A Strange Encounter

In the summer of 1902, James Joyce completed his studies at the Catholic University of Ireland. The following autumn he sat his exams in the Royal University, and on 31 October he was awarded a Bachelor of Arts in Modern Languages. By this time the young Dubliner was making a name for himself as a precocious and prickly critic of contemporary literature. A few of his reviews and essays had already appeared in print. He had electrified the university’s Literary and Historical Society with his papers on Drama and Life and James Clarence Mangan. He had even written a letter in Dano-Norwegian to his hero Henrik Ibsen. The time had come for Mr Joyce to formally introduce himself to the leading lights of the Irish Literary Revival.

He presented himself first to George Russell, who was approachable and indulgent, and who, unlike Yeats, was always in Dublin. Russell, then thirty-five, was the youngest of the senior figures of the revival ... Russell’s mysticism, and his bearded prolixity, led skeptics to suppose he was foolish, but in fact he was clever ... and he had a sharp eye for ability in others and an unexpected power of criticism. (Ellmann 98)

It was August 1902. Joyce was twenty years old and currently domiciled at 32 Glengariff Parade, on the northside of Dublin. One evening, at around 10 pm, he made his way across town to the leafy southside suburb of Rathgar, where Russell lived. He located 25 Coulson Avenue, the Russells’ unassuming terraced house, and knocked on the door. No answer. For the next two hours he walked up and down the avenue, keeping a close eye on the empty house. Finally, at midnight, Russell returned home. Joyce ran up and knocked on the door and when Russell answered, he asked if it was too late to talk.

— It is never too late to talk, Russell replied, and invited him in.

They sat down and Russell looked at Joyce inquiringly. Since Joyce seemed to experience some difficulty in explaining why he had come, Russell talked for a bit ... [Joyce] allowed that Russell had written a lyric or two, but complained that Yeats had gone over to the rabblement. He spoke slightingly of everyone else, too. When pressed by Russell, he read his own poems, but not without first making clear that he didn’t care what Russell’s opinion of them might be. Russell thought they had merit but urged him to get away from traditional and classical forms, concluding (as he afterwards remembered with great amusement), “You have not enough chaos in you to make a world.” (Ellmann 99)

The two men talked for several hours on a variety of subjects, including Theosophy, which was then in vogue in Dublin. George Russell—or AE, as he was also known—was the founder of the Dublin Hermetic Society, an offshoot of Madame Blavatsky’s Theosophical Society. When they finally called it a night, the ice had been broken and Joyce had been inducted into Russell’s literary circle.

This epochal encounter—or, rather, the garbled version of it that soon acquired currency in Dublin—would later be commemorated by Joyce in the Aeolus episode of Ulysses:

— Professor Magennis was speaking to me about you, J. J. O’Molloy said to Stephen. What do you think really of that hermetic crowd, the opal hush poets: A. E. the master mystic? That Blavatsky woman started it. She was a nice old bag of tricks. A. E. has been telling some yankee interviewer that you came to him in the small hours of the morning to ask him about planes of consciousness. Magennis thinks you must have been pulling A. E.’s leg. (Joyce 178. See also 237)

Joyce had clearly made an impression on Russell. A few days later AE arranged another meeting at his home in Rathgar, and shortly after the first meeting he wrote to William Butler Yeats about the young man:

I want you very much to meet a young fellow named Joyce whom I wrote to Lady Gregory about half-jestingly. He is an extremely clever boy who belongs to your clan more than to mine and still more to himself. But he has all the intellectual equipment, culture and education, which all our other friends here lack, and I think writes amazingly well in prose ... (Letters of James Joyce, Volume 2, p 11)

If Joyce had made an impression on Russell, Russell had also made an impression on Joyce. The verdict he had delivered on the young emergent artist was prescient and had a lasting impact on the course of Joyce’s literary career:

You have not enough chaos in you to make a world.

Fast forward eleven years to 1913. Joyce is now in his thirties. He has been to Paris. He has written Dubliners and A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. He has killed his mother. During these years, his little lump of chaos has been growing and growing. And out of this chaos James Joyce finally creates a world, and he calls it Ulysses.

Cosmos and Chaos

When Russell told the young Joyce that he had not enough chaos in him to make a world, he was alluding to the ancient Greek concept of creation, which is quite different from the one we find in the Bible. In Genesis, God creates a world out of nothing. In the Proteus episode of Ulysses Stephen Dedalus ponders his own creation in a similar vein:

One of her sisterhood lugged me squealing into life. Creation from nothing. (Joyce 46)

But this was an alien concept to the ancient Greeks. How can something arise out of nothing? Ex nihilo nihil fit is how the Romans succinctly put it, but we find the same idea in the early Greek philosopher Parmenides:

... Being has no coming-into-being and no destruction ... for what creation of it will you look for? How, whence [could it have] sprung? Nor shall I allow you to speak or think of it as springing from Not-Being; for it is neither expressible nor thinkable that What-Is-Not is ... Nor will the force of credibility ever admit that anything should come into being, beside Being itself, out of Not-Being. (Freeman 43)

Before Parmenides, the poet Hesiod described how all things had their beginning in a primordial being called Chaos:

Verily at first Chaos came to be, but next wide-bosomed Earth, the ever-sure foundation of all the deathless ones who hold the peaks of snowy Olympus, and dim Tartarus in the depth of the wide-pathed Earth, and Eros (Love), fairest among the deathless gods, who unnerves the limbs and overcomes the mind and wise counsels of all gods and all men within them. From Chaos came forth Erebus and black Night ... (Hesiod 87-88)

To the ancient Greeks, creation was not an act of bringing forth something out of nothing. It was, rather, an act of procreation. Hesiod’s Chaos was the mother—and father—of the first generation of primitive deities. In time, however, this act of procreation gave way to a cosmogonical process according to which chaos—now conceived of as an inanimate substance—is transformed into cosmos.

χάος [chaos] – the first state of the universe ... sometimes the rudis indigestaque moles, out of which the universe was created (Liddell & Scott 1713)

κόσμος [cosmos] – I: order : good order : form, fashion – II: an ornament, decoration, embellishment, dress, especially of women ... IV: the world or universe, from its perfect order and arrangement, opposed to the indigesta moles of Chaos (Liddell & Scott 836)

Significantly, the word cosmos encompasses the notion of beauty. We still use the word cosmetic to describe something that enhances one’s physical beauty. Chaos, by contrast, is inherently ugly and repellent:

Before the sea was, and the lands, and the sky that hangs over all,

The face of Nature showed alike in her whole round,

Which state have men called chaos: a rough, unordered mass of things,

Nothing at all save lifeless bulk and warring seeds

Of ill-matched elements heaped in one.

(Ovid 1:5-9)

Rudis indigestaque moles, a rough, unordered mass of things: that is how Ovid conceived of chaos. And it is how we commonly conceive of it today.

In the creation of the world, then, something ugly and unordered is transformed into something beautiful and ordered. When Plato describes this process in his dialogue the Timaeus, Hesiod’s procreation has all but disappeared. And Plato adds a new twist to the old myth by introducing a creator—a craftsman or artisan—who gives shape and order to the primordial chaos. δημιουργός, is the Greek term he uses for this craftsman, a word which has since passed into English as demiurge:

- δημιουργός [dēmiourgos] – 1: one who works for the people, a skilled workman, handicraftsman ... a member of the artisan class at Athens – 2: the Maker of the world (Liddell & Scott 339)

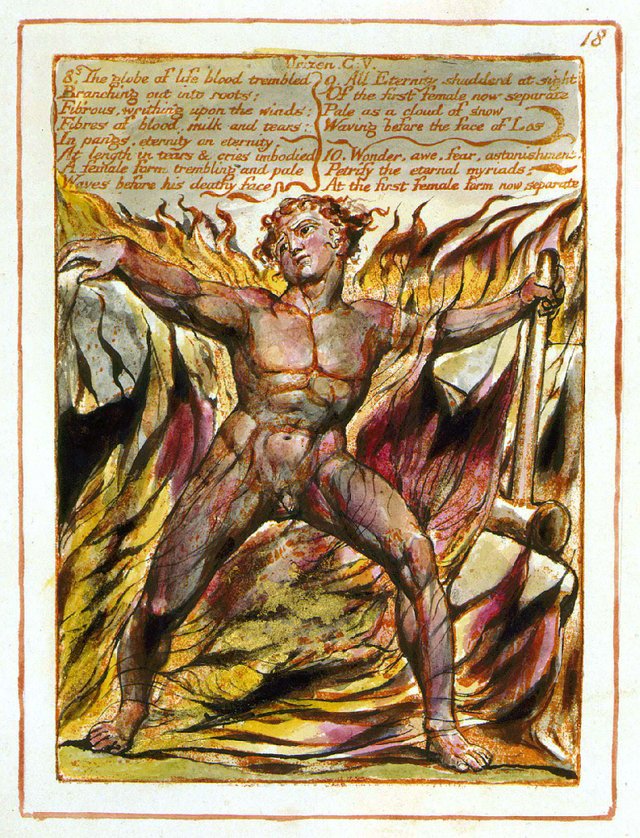

In Proteus, Stephen identifies Plato’s Demiurgos with William Blake’s Los, who is also a creator and a craftsman—Blake depicts him as a smith armed with a mallet.

Timaeus describes the work of Plato’s demiurge thus:

Now everything that comes to be must of necessity come to be by the agency of some cause, for it is impossible for anything to come to be without a cause. So whenever the craftsman looks at what is always changeless and, using a thing of that kind as his model, reproduces its form and character, then, of necessity, all that he so completes is beautiful. (Plato 1234-1235)

Artistic Creation

In transforming chaos into cosmos, the demiurge is attempting to imitate the perfect Platonic Forms, which exist eternally on a spiritual plane. It is but a step from this to the Greek notion of artistic creation, which was also conceived in terms of imitation—mimesis. In Plato’s most famous work, The Republic, Critias notes:

Let us consider the graphic art of the painter that has as its object the bodies of both gods and men and the relative ease and difficulty involved in the painter’s convincing his viewers that he has adequately represented the objects of his art. (The Republic, Book 10, 107b)

Aristotle even viewed the literary, dramatic and musical arts as essentially imitative:

Epic poetry and tragedy, as also comedy, dithyrambic poetry, and most flute-playing and lyre-playing, are all, viewed as a whole, modes of imitation. (Poetics §1)

But whereas Plato’s demiurge imitates the perfect Forms, artists imitate nature, which is itself but an imperfect imitation of the Forms. As Shakespeare’s Hamlet famously put it:

... o’erstep not the modesty of nature : for any thing so overdone is from the purpose of playing, whose end, both at the first and now, was and is, to hold, as ’twere, the mirror up to nature; (Hamlet, Act 3, Scene 2)

So the ancient Greeks themselves had already drawn the analogy between the Creation of the World by the gods and the creation of works of art by men. Just as Plato’s demiurge converts chaos into cosmos, so the sculptor takes a shapeless lump of rock and transforms it into a thing of beauty. And the better the imitation, the finer the work of art is judged to be.

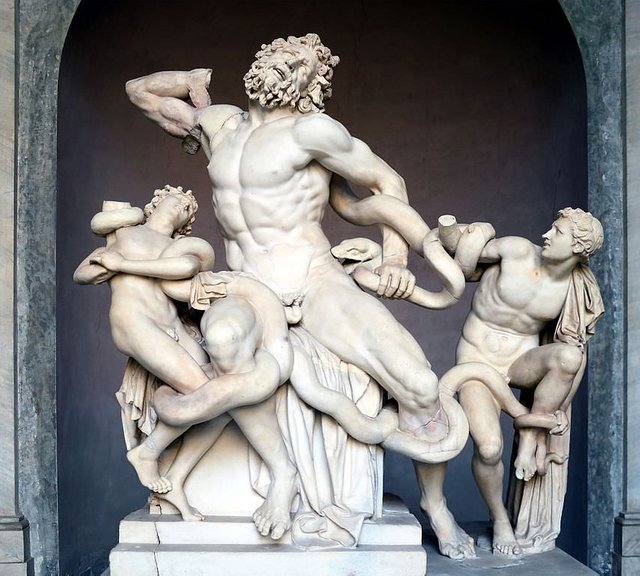

The Laocoön

In Book 36 of his encyclopaedic Natural History, Pliny the Elder surveyed the stone sculpture of his day. One of the works he mentioned was:

... the Laocoön ... in the palace of the Emperor Titus, a work that may be looked upon as preferable to any other production of the art of painting or of statuary. It is sculptured from a single block, both the main figure as well as the children, and the serpents with their marvellous folds. This group was made in concert by three most eminent artists, Agesander, Polydorus, and Athenodorus, natives of Rhodes. (Pliny 36:4)

As Pliny’s translators John Bostock and H T Riley note:

This group is generally supposed to have been identical with the Laocoön still to be seen in the Court of the Belvedere, in the Vatican at Rome; having been found, in 1506, in a vault beneath the spot known as the Place de Sette Sale, by Felix de Fredi, who surrendered it, in consideration of a pension, to Pope Julius II. The group, however, is not made of a single block, which has caused some to doubt its identity : but it is not improbable, that when originally made, its joints were not perceptible to a common observer. The spot, too, where it was found was actually part of the palace of Titus. It is most probable that the artists had the beautiful episode of Laocoön in view, as penned by Virgil, [Aeneid Book 2]. (Pliny 36:4,fn)

Laocoön was a Trojan priest, who tried to warn his fellow citizens not to bring the Wooden Horse into the city:

Laocoön in hot haste runs down from the citadel’s height, and cries from afar: “My poor countrymen, what monstrous madness is this? Do you believe the foe has sailed away? Do you think that any gifts of the Greeks are free from treachery? Is Ulysses known to be this sort of man? Either enclosed in this frame there lurk Achaeans, or this has been built as an engine of war against our walls, to spy into our homes and come down upon the city from above; or some trickery lurks inside. Men of Troy, trust not the horse. Whatever it be, I fear the Greeks, even when bringing gifts.” So saying, with mighty force he hurled his great spear at the beast’s side and the arched frame of the belly. The spear stood quivering and with the cavity’s reverberation the vaults rang hollow, sending forth a moan. (Virgil Aeneid 2:40-52)

Timeo Danaos et dona ferentis, frequently paraphrased as Beware of Greeks bearing gifts, is possibly the most famous line Virgil ever penned. But for all his eloquence, Laocoön could not match the wily tongue of Sinon, the Achaean spy who tricked the Trojans into doing the very thing Laocoön warned them not to do. The Trojans were convinced, however, by the fate of Laocoön and his sons:

... from Tenedos, over the peaceful depths—I shudder as I speak—a pair of serpents with endless coils are breasting the sea and side by side making for the shore. Their bosoms rise amid the surge, and their crests, blood-red, overtop the waves; the rest of them skims the main behind and their huge backs curve in many a fold; we hear the noise as the water foams. And now they were gaining the fields and, with blazing eyes suffused with blood and fire, were licking with quivering tongues their hissing mouths. Pale at the sight, we scatter. They in unswerving course make for Laocoön; and first each serpent enfolds in its embrace the small bodies of his two sons and with its fangs feeds upon the hapless limbs. Then himself too, as he comes to their aid, weapons in hand, they seize and bind in mighty folds; and now, twice encircling his waist, twice winding their scaly backs around his throat, they tower above with head and lofty necks. He the while strains his hands to burst the knots, his fillets steeped in gore and black venom; the while he lifts to heaven hideous cries, like the bellowings of a wounded bull that has bled from the altar and shaken from its neck the ill-aimed axe. But, gliding away, the dragon pair escape to the lofty shrines, and seek fierce Tritonia’s citadel, there to nestle under the goddess’s feet and the circle of her shield. Then indeed a strange terror steals through the shuddering hearts of all, and they say that Laocoön has rightly paid the penalty of crime, who with his lance profaned the sacred oak and hurled into its body the accursed spear. (Virgil, Aeneid, Book 2:199-231)

Lessing

In the 18th century, the Laocoön was the inspiration for Gotthold Ephraim Lessing’s monograph Laocoön: An Essay on the Limits of Painting and Poetry. Lessing’s central thesis is that there are two types of art, one exemplified by painting and one by poetry: the former is spatial, while the latter is temporal:

... all the representations of Art are necessarily restricted by its material limits to a single instant of time. If it be true that the artist can adopt from the face of ever-varying nature only so much of her mutable effects as will belong to one single moment, and that the painter, in particular, can seize this single moment only under one solitary point of view;—if it be true also that his works are intended, not to be merely glanced at, but to be long and repeatedly examined;—then it is clear that the great difficulty will be to select such a moment and such a point of view as shall be sufficiently pregnant with meaning ... it is not at all necessary for the poet to concentrate his picture into a single moment of time. He takes up each action at his will from its very commencement, and traces it, through all its various changes, to the conclusion ... It may, I presume, be taken for granted, that succession of time is the sphere of the poet, as space is that of the painter. (Lessing 28-29 ... 37 ... 177)

In Section 20, Lessing writes:

Der Dichter, der die Elemente der Schönheit nur nacheinander zeigen könnte, enthält sich daher der Schilderung körperlicher Schönheit, als Schönheit, gänzlich. Er fühlt es, daß diese Elemente, nacheinander geordnet, unmöglich die Wirkung haben können, die sie, nebeneinander geordnet, haben.

The poet, who can indicate the elements of beauty only consecutively [nacheinander], abstains therefore altogether from the delineation of corporeal beauty, qua beauty. He feels that these elements, when arranged in succession[nacheinander], cannot possibly produce the same effect as when brought into immediate contact with each other [nebeneinander]; (Lessing 204-205)

This is the passage that Stephen alludes to when he quotes those bold German words on the opening page of Proteus. Although Stephen does not make things easy for the reader by identifying the author, Lessing is eventually named explicitly, in the Circe episode, rewarding those who are still reading:

STEPHEN : Why striking eleven? Proparoxyton. Moment before the next Lessing says. Thirsty fox. (He laughs loudly) Burying his grandmother. Probably he killed her. (Joyce 666)

Years earlier, Joyce had recorded his opinion of Lessing in Stephen Hero, the unfinished semi-autobiographical novel that eventually yielded place to A Portrait:

Stephen did not attach himself to art in any spirit of youthful dillettantism but strove to pierce to the significant heart of everything. He doubled backwards into the past of humanity and caught glimpses of emergent art as one might have a vision of the pleisiosauros emerging from his ocean of slime. He seemed almost to hear the simple cries of fear and joy and wonder which are antecedent to all song, the savage rhythms of men pulling at the oar, to see the rude scrawls and the portable gods of men whose legacy Leonardo and Michelangelo inherit. And over all this chaos of history and legend, of fact and supposition, he strove to draw out a line of order, to reduce the abysses of the past to order by a diagram. The treatises which were recommended to him he found valueless and trifling; the Laocoon of Lessing irritated him. He wondered how the world could accept as valuable contributions such fanciful generalisations. (Joyce, Stephen Hero 33)

Joyce may also have been thinking of the Laocoön when he wrote the following in Paris, less than a year after his encounter with Russell:

It is false to say that sculpture (for instance) is an art of repose if by that be meant that sculpture is unassociated with movement. Sculpture is associated with movement in as much as it is rhythmic; for a work of sculptural art must be surveyed according to its rhythm and this surveying is an imaginary movement in space. It is not false to say that sculpture is an art of repose in that a work of sculptural art cannot be presented as itself moving in space and remain a work of sculptural art. (Joyce, Paris Notebook, 27 March 1903)

Proteus

The Proteus episode in Ulysses is all about this artistic process of transforming chaos into cosmos. Here we see a younger Joyce—the one Russell met—trying to create art out of his little store of chaos.

Rhythm begins, you see. I hear. (Joyce 46)

The result, hurriedly scribbled on a scrap of torn paper, is not great: four lines of sentimental verse. We have to wait till the Aeolus episode to hear them in their finished form:

On swift sail flaming

From storm and south

He comes, pale vampire,

Mouth to my mouth.

(Joyce 168)

In a later episode, Wandering Rocks, Haines the Englishman browses through Douglas Hyde’s Love Songs of Connacht, which he has just bought at Gill’s bookshop on O’Connell Street. The ninth song in this collection is My Grief on the Sea, the last verse of which is translated by Hyde thus:

And my love came behind me—

He came from the South;

His breast to my bosom,

His mouth to my mouth.

(Hyde 31)

So Stephen has not tried to play God by creating out of nothing. Instead, he has simply transformed Hyde’s lyric. In his defence it might be stated that Hyde too did not create out of nothing. His lyric is a free translation of an anonymous Irish song, Mo Bhrón air an bhFairrge. But why does Joyce portray his younger self as a plagiarist? Perhaps because Stephen—as AE perceptively noted—does not yet have enough chaos of his own to create a world. He is obliged to steal some items from Hyde’s rag-and-bone shop.

Curiously, Stephen has also anticipated by about a century a recent vogue for rewriting classic works of literature with vampires, werewolves or zombies—mashup is the technical term. Among the more popular examples of this genre one might mention Pride and Prejudice and Zombies by Seth Grahame-Smith. In the spirit of these bizarre reimaginings, Stephen’s verse might be called Love Songs of Connacht with Vampires.

Dracula was written by Joyce’s fellow Dubliner Bram Stoker and published in 1897, when Joyce was fifteen. Did he ever read it?

Full Circle

From his reading of Aristotle, Joyce developed his own theory of artistic creation, one which went back to that primordial idea of Hesiod’s, in which the creation of the world began with an act of procreation. When Aristotle claimed that art imitates life, Joyce took him at his word and interpreted this to mean not—as most scholars interpret it—that the artist creates objects that somehow hold a mirror up to nature, but, rather, that the very act of artistic creation is analogous to the act of sexual procreation. The objet d’art is the artist’s offspring, and the true artist must become, like Hesiod’s Chaos, both the father and the mother of that child:

“e tekne mimeitai ten phusin”—This phrase is falsely rendered as “Art is an imitation of Nature.” Aristotle does not here define art : he says only “Art imitates Nature” and meant that the artistic process is like the natural process... (Joyce, Paris Notebook 27 March 1903. The quote from Aristotle is taken from Fragment 11 of his lost dialogue Protrepticus : ἡ τέχνη μιμεῖται τὴν φύσιν.)

But this is a discussion which really belongs in Scylla and Charybdis.

References

- Aristotle, Poetics, Samuel Henry Butcher (translator), Macmillan & Co, Limited, London (1922)

- Aristotle, Protrepticus, Fragments, David Ross, **The Works of Aristotle, Volume 12, Select Fragments, The Clarendon Press, Oxford (1952)

- Richard Ellmann, James Joyce, New and Revised Edition, Oxford University Press, Oxford (1982)

- Kathleen Freeman, Ancilla to the Pre-Socratic Philosophers, Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA (1948)

- Hesiod, Theogony, in Hugh G Evelyn-White (translator), Hesiod, The Homeric Hymns and Homerica, William Heinemann, London (1914)

- Douglas Hyde, Love Songs of Connacht, Fourth Edition, Gill & Son, Dublin (1905)

- James Joyce, Paris Notebook, The Joyce Papers 2002, National Library of Ireland, MS 36,639/2/A,

- James Joyce, Ulysses, Penguin Books Ltd, London (1992)

- James Joyce, The Letters of James Joyce, Volumes I, II, III, Stuart Gilbert (editor), Richard Ellmann (editor), Viking Press, New York (1966)

- Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, Laocoön: or. The Limits of Poetry and Painting, Translated from the German by William Ross, J Ridgway & Sons, London (1836)

- Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, Eighth Edition, American Book Company, New York (1901)

- Publius Ovidius Naso, Metamorphoses, With an English Translation by Frank Justus Miller, Volume 1, Loeb Classical Library L042, Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA (1921)

- Plato, Complete Works, John M Cooper (editor), Hackett Publishing Company, Indianapolis IN (1997)

- William Shakespeare, Hamlet, Prince of Denmark, Introduction and Notes by Kenneth Deighton, Macmillan & Co, Limited, London (1919)

Image Credits

- James Joyce in 1904: C P Curran Collection (Cur P1), UCD Library Special Collections, IVRLA, UCD, Fair Use

- George Russell: John Butler Yeats (artist), National Gallery of Ireland, NGI 871, Public Domain

- William Blake’s Los: Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain

- Richard Ellmann: Wikipedia, Copyright Unknown, Fair Use

- Ulysses: © The Manhattan Rare Book Company, Fair Use

- Parmenides: Wikimedia Commons, GNU Free Documentation License

- The Laocön: Wikimedia Commons, © 2014 LivioAndranico, Creative Commons License

- G E Lessing: Wikimedia Commons, Anna Rosina de Gasc (artist), Public Domain

- Sandymount Strand: Geograph Ireland, © Doug Lee, Creative Commons License

- Bram Stoker: Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain

- The Beach at Sandymount: Geograph Ireland, © Doug Lee, Creative Commons License

Hello great friend, it's good that you're back with us sharing those fantastic stories

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

you are a great historian, passionate and managing to show what history really is, you missed yourself brother

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

It is an extraordinary writing a great writer with very good works and you share it with us friend thanks for such good post greetings

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Nice history post bro

Posted using Partiko iOS

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

your presence in the community is really important, you feed them with great history, brother, blessings, do not miss so much

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Thanks for the friend support and for sharing with us all your post I love the story good job you are a big one of this great community

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Very nice post. Thank you for sharing information

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit