The Siwalik Hills is Chapter 6, Section 3, of Immanuel Velikovsky’s Earth in Upheaval. The Sivalik Hills, as they are also known, comprise the foothills of the Himalayas. Lying immediately to the south of the Himalayas, they extend for more than 2000 km across India, Nepal, and Pakistan. Since the 19th century they have been recognized as one of the richest sources of megafauna fossils in Asia:

Animal bones of species and genera, living and extinct, were found there in most amazing profusion. Some of the animals looked as though nature had conducted an abortive experiment with them and had discarded the species as not fit for life ... The Siwalik fossil beds are stocked with animals of so many and such varied species that the animal world of today seems impoverished by comparison. (Velikovsky 73)

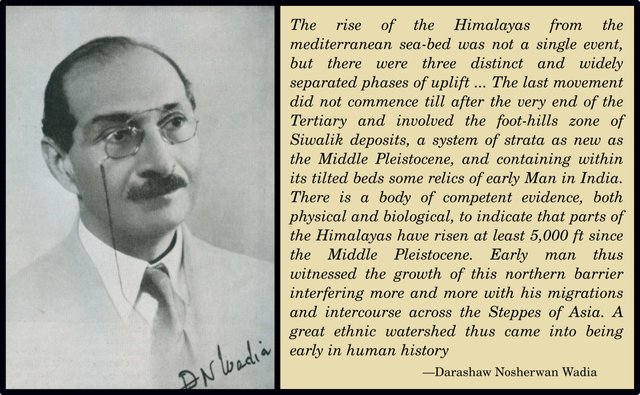

Velikovsky is quick to quote the local geologist Darashaw Nosherwan Wadia on the possible implications of the incredible range of biodiversity exhibited by the Siwalik deposits:

Rapid evolution of Siwalik fauna—After the first few glimpses of the mammalian fauna of the Tertiary era in the Bugti beds and that in the Perim Island, this sudden bursting on the stage of such a varied population of herbivores, carnivores, rodents and of primates, the highest order of the mammals, must be regarded as a most remarkable instance of rapid evolution of species. Many factors must have helped in the development and differentiation of this fauna; among those favourable conditions, the abundance of food-supply by a rich angiospermous vegetation, which flourished in uncommon profusion, and the presence of suitable physical environments, under a genial climate, in a land watered by many rivers and lakes, must have been the most prominent. (Wadia 1944:268)

These fossils are dated to the Late Tertiary or Neogene Period (approximately 20-3 Mya). Wadia characterized the Siwalik System as Helvetian to Lower Pleistocene, or 15-3 Mya (Wadia 1944:271). It is not at all clear that Wadia’s rapid evolution means anything more than rapid relative to the tens of millions of years it might otherwise have taken for natural selection to have produced such a degree of biodiversity. He was no catastrophist, but he did believe that the Siwalik Hills were formed by very recent uplifts (Wadia 1964:4-5):

Velikovsky also briefly quotes Helmut de Terra, a German geologist who was introduced to the reader in the previous section. No citation is giving for the quotation, but it comes from Studies on the Ice Age in India and Associated Human Cultures (de Terra 224). De Terra consistently placed the fossiliferous deposits of the Upper Siwalik in the early Pleistocene:

The 2,000 feet of fossiliferous Upper Siwalik beds underlying this zone indicate clearly a prolonged sedimentation which embraces the early Pleistocene. (de Terra 214)

He also assigned the Lower Siwalik to the relatively recent Pliocene Epoch (5.3-2.6 Mya):

These comprise the Middle and Lower Siwaliks, mainly of Pliocene age ... (de Terra 18)

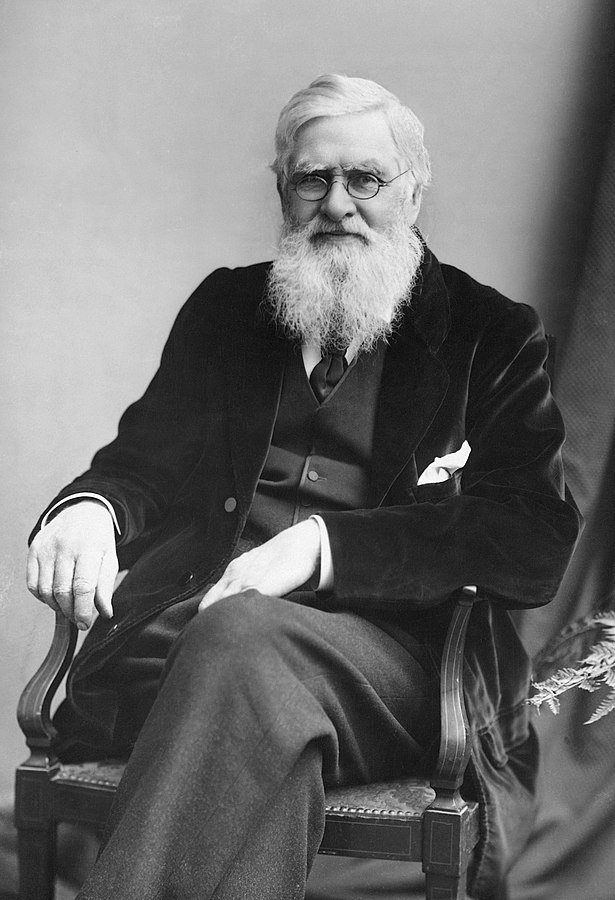

Another famous naturalist is alluded to by Velikovsky in this paragraph but without any formal citation:

A. R. Wallace, who shares with Darwin the honor of being the originator of the theory of natural selection, was among the first to draw attention, in terms of astonishment, to the Siwalik extinction. (Velikovsky 73)

As we shall see, Velikovsky took this allusion to Wallace from Wadia. The latter did not provide a citation, but could only be referring to Alfred Russel Wallace’s book The Geographical Distribution of Animals (London 1876):

Upper Miocene Deposits of the Siwalik Hills and other Localities in N. W. India.

These remarkable fresh-water deposits form a range of hills at the foot of the Himalayas, a little south of Simla. They were investigated for many years by Sir P. Cautley and Dr. Falconer, and add greatly to our knowledge of the early fauna of the Old World continent. (Wallace 121)

Finally, Velikovsky quotes from Joseph Trank Wheeler’s The Zonal-Belt Hypothesis, an unusual work which attempts to explain ice ages in terms of atmospheric temperature belts. Like Velikovsky, Wheeler drew support for his controversial hypothesis from world mythology. Today, Wheeler has few adherents and information on him is hard to come by. He was born in Philadelphia on 30 May 1868.

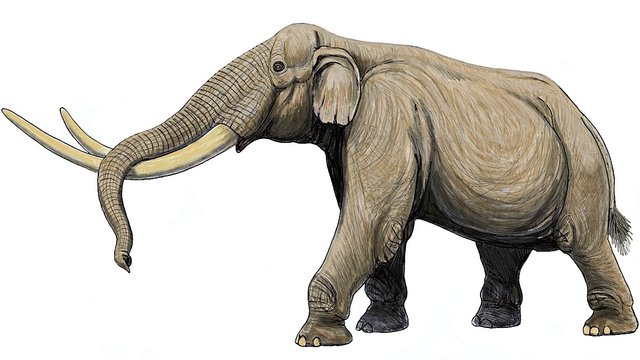

Velikovsky is particularly struck by the variety and unusual nature of the Siwalik fossils:

The Elephas ganesa [Stegodon ganesa], an elephant species found in the Siwalik Hills, had tusks about fourteen feet [4 m] long and over three feet [1 m] in circumference. One author says of them: “It is a mystery how these animals ever carried them, owing to their enormous size and leverage.” (Velikovsky 73)

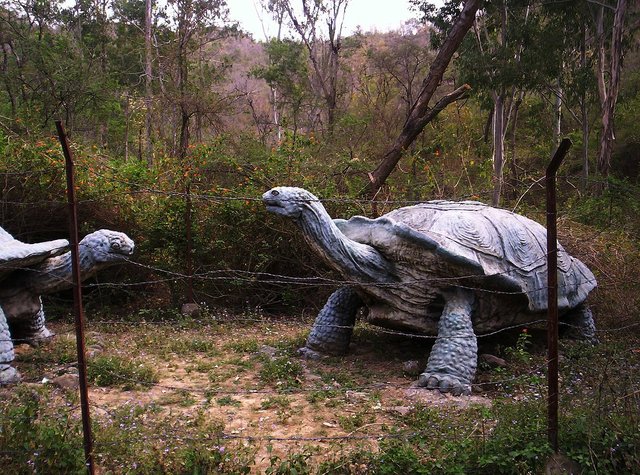

Giant Tortoise

Velikovsky also draws the reader’s attention to another curious anomaly:

Some of the animals looked as though nature had conducted an abortive experiment with them and had discarded the species as not fit for life. The carapace of a tortoise twenty feet long [6 m] was found there; how could such an animal have moved on hilly terrain? (Velikovsky 73, Wadia 1944:268)

Wadia did gives the Colossochelys atlas (also known as the Magalochelys atlas) these dimensions, but today’s textbooks give this species a maximum length of only 2.7 m, with a carapace over 2 m long. Wadia was quoting the English palaeontologist Gideon Mantell, but he did not provide a citation. I have not been able to identify the work from which the quotation was taken, but I did find a work by Mantell in which he could be understood to be endorsing such a figure: Petrifactions and Their Teachings, or A Hand-Book to the Gallery of Organic Remains of the British Museum:

With these cursory observations, I would introduce the reader to Room I., requesting him to notice on the lobby, to the left of the doorway, an admirable model (executed by Mr. Dew, the palæontological modeller and sculptor of the Museum) of the carapace, or shell of a young individual of the extinct Colossal Tortoise of India (Colossochelys atlas), of which there are many fossil remains in the collection. This specimen is ten feet long, twenty-five feet in horizontal circumference, and fifteen feet in girth in a vertical direction; gigantic as are these proportions, they are one-third less than those of the adult original. (Mantell 9-11)

Extending these figures by one third gives the species a length of over 13 ft, a circumference of over 37 ft, and a height (“girth in the vertical direction”) of 20 ft. This figure of “20 feet in length” was given by Richard Owen in Palæontology, or Systematic Summary of Extinct Animals and Their Geological Relations, which first appeared in 1860, nine years after Mantell’s work (Owen 319). Mantell, himself, later mentioned the same species—referring to it now as Megalochelys atlas—and gives a smaller figure for the length of the adult carapace:

This case is filled with the remains of the carapace, plastron, &c. of several individuals of the Megalochelys Atlas; a stupendous fossil tortoise, discovered by Major Cautley and Dr. Falconer in the Eocene strata of the Sewalik Hills; with the bones of Mastodons, Elephants, &c., to be described in the sequel. A model of a young individual, constructed by Mr. Dew, is placed near the entrance of Room I., and is described ante, p. 11. Some of these relics show that the length of the carapace was upwards of twelve feet in adult specimens. (Mantell 77)

Even this is almost twice as long as modern palaeontologists are willing to go.

Mass Extinction

If the Siwalik deposits are remarkable for the suddenness with which such a rich profusion of unusual species appeared, they are no less remarkable for the suddenness with which the vast majority of these species subsequently vanished. Velikovsky’s principal source, Wadia, attributed this mass extinction to the onset of an Ice Age during the Pleistocene Epoch:

The extinction of the Siwalik mammals—one further evidence—Further evidence, from which an inference can be drawn of an Ice Age in the Pleistocene epoch in India, is supplied by the very striking circumstance to which the attention of the world was first drawn by the great naturalist, Alfred Russel Wallace. The sudden and widespread reduction, by extinction, of the Siwalik mammals is a most startling event for the geologist as well as the biologist The great Carnivores, the varied races of elephants belonging to no less than twenty-five to thirty species, the Sivatherium and numerous other tribes of large and highly specialised Ungulates which found such suitable habitats in the Siwalik jungles of the Pliocene epoch, are to be seen no more in an immediately succeeding age. This sudden disappearance of the highly organised mammals from the fauna of the world is attributed by the great naturalist to the effect of the intense cold of a Glacial age. (Wadia 1944:279-281)

In Wallace’s own words:

It is clear, therefore, that we are now in an altogether exceptional period of the earth’s history. We live in a zoologically impoverished world, from which all the hugest, and fiercest, and strangest forms have recently disappeared; and it is, no doubt, a much better world for us now they have gone. Yet it is surely a marvellous fact, and one that has hardly been sufficiently dwelt upon, this sudden dying out of so many large mammalia, not in one place only but over half the land surface of the globe. We cannot but believe that there must have been some physical cause for this great change; and it must have been a cause capable of acting almost simultaneously over large portions of the earth’s surface, and one which, as far as the Tertiary period at least is concerned, was of an exceptional character. Such a cause exists in the great and recent physical change known as “the Glacial epoch.” We have proof in both Europe and North America, that just about the time these large animals were disappearing, all the northern parts of these continents were wrapped in a mantle of ice; and we have every reason to believe that the presence of this large quantity of ice (known to have been thousands of feet if not some miles in thickness) must have acted in various ways to have produced alterations of level of the ocean as well as vast local floods, which would have combined with the excessive cold to destroy animal life. (Wallace 150-151)

To Wadia’s account of this mass extinction, Velikovsky adds the following pertinent comment:

It used to be assumed that the advent of the Ice Age killed them, but subsequently it has been recognized that great destructions took place in the age of man, much closer to our day. (Velikovsky 74)

This is the kernel of the matter—the element that makes these fossils relevant to Earth in Upheaval—but, crucially, Velikovsky provides no citation for this assertion. It is possible that he is referring to Wadia’s The Himalaya Mountains: Their Age, Origin And Sub-Crustal Relations, which was quoted alongside the image of Wadia above. This paper was first published in The March of India (Volume 5, Issue2) in 1952, shortly before Velikovsky wrote Earth in Upheaval. Wadia does synchronize the uplift of the Siwalik Hills with the appearance of early Man in India, but he only dates these events vaguely to since the Middle Pleistocene. Today, the Middle Pleistocene, or Chibanian, is dated to 770,000–126,000 years ago. Wadia’s since the Middle Pleistocene does not necessarily mean the same as Velikovsky’s much closer to our time.

But if these extinctions were not necessarily of recent event, were they at least of a catastrophic nature? Velikovsky would like to think so, and he calls upon Wadia for support:

The idea of the older geologists that the whole Siwalik system of rocks were deposits of the nature of alluvial fans, talus slopes, etc., at the debouchers of the Himalayan rivers very much along the sites of their present-day channels, does not appear to be tenable on the ground of the remarkable homogeneity that the deposits possess. Not only do they show on the whole uniformity of lithological composition at such distant centres as Hardwar, Simla hills, Kangra, Jammu and Potwar, but also there is a striking structural unity of disposition along a definite and continuous line of strike. This negatives any theory of the deposition of these rocks in a multitude of isolated basins. (Wadia 1944:270)

In other words, the deposits were created in several unconnected basins at the same time and by the same event. This certainly sounds like a catastrophic event of wide geographical extent—such as a megaflood.

The Irrawaddy Deposits

While describing the Siwalik deposits, Alfred Russel Wallace also drew attention briefly to similar deposits in the valley of the Irrawaddy River in Burma, or Myanmar (Wallace 121, 123). Wadia describes two fossiliferous horizons in these deposits, the uppermost of which contains fossils of mastodons, stegodons, hippopotami and oxen. As Velikovsky notes, there are clear signs in this horizon of a mass extinction event during the Ice Age:

The sediments are remarkable for the large quantities of fossil-wood associated with them and they were originally known as the “fossil-wood group”. Hundreds and thousands of entire trunks of silicified trees and huge logs lying in the sandstones suggest the denudation of thickly forested eastern slopes of the Arakan Yoma. (Wadia 1944:275)

Velikovsky is surely justified in asking what natural force could wreak such havoc over such a large area:

Animals met death and extinction by the elementary forces of nature, which also uprooted forests and from Kashmir to Indo-China threw sand over species and genera in mountains thousands of feet high. (Velikovsky 75)

No satisfactory answer has been found. The Siwaliks have not yet given up all of their secrets.

And that’s a good place to stop.

References

- Gideon Algernon Mantell, Petrifactions and Their Teachings, or A Hand-Book to the Gallery of Organic Remains of the British Museum, Henry G Bohn, London (1851)

- Richard Owen, Palæontology, or Systematic Summary of Extinct Animals and Their Geological Relations, Adam and Charles Black, Edinburgh (1861)

- Helmut de Terra & Thomas Thomson Paterson, Studies on the Ice Age in India and Associated Human Cultures, Publications of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, Number 493, Washington, DC (1939)

- Immanuel Velikovsky, Earth in Upheaval, Pocket Books, Simon & Schuster, New York (1955, 1977)

- Darashaw Nosherwan Wadia, Geology of India, Second Edition, Macmillan and Co, Limited, London (1944)

- Dareshaw Nosherwan Wadia, The Himalaya Mountains: Their Age, Origin And Sub-Crustal Relations, National Institute of Sciences of India, New Delhi (1964)

- Alfred Russel Wallace, The Geographical Distribution of Animals, Volume 1, Macmillan and Co, London (1876)

- Joseph Trank Wheeler, The Zonal-Belt Hypothesis: A New Explanation of the Cause of the Ice Ages, J B Lippincott Company, Philadelphia (1908)

Image Credits

- The Siwalik Hills: Shivalik Hills, Sikkim, India, © Spattadar (photographer), Creative Commons License

- Dareshaw Nosherwan Wadia: D N Wadia: A Biographical Sketch, Journal of the Palaeontological Society of India, Volume 2, Pages 2-8, Centre of Advanced Study in Geology, University of Lucknow, Lucknow, India (1956), Fair Use

- Alfred Russel Wallace: London Stereoscopic and Photographic Company, Public Domain

- Stegodon ganesa (Elephas ganesa): DiBgd (artist), Creative Commons License

- Life-Size Models of Megalochelys atlas: Shivalik Fossil Park, Himachal Pradesh, India, © Vjdchauhan (photographer), Creative Commons License

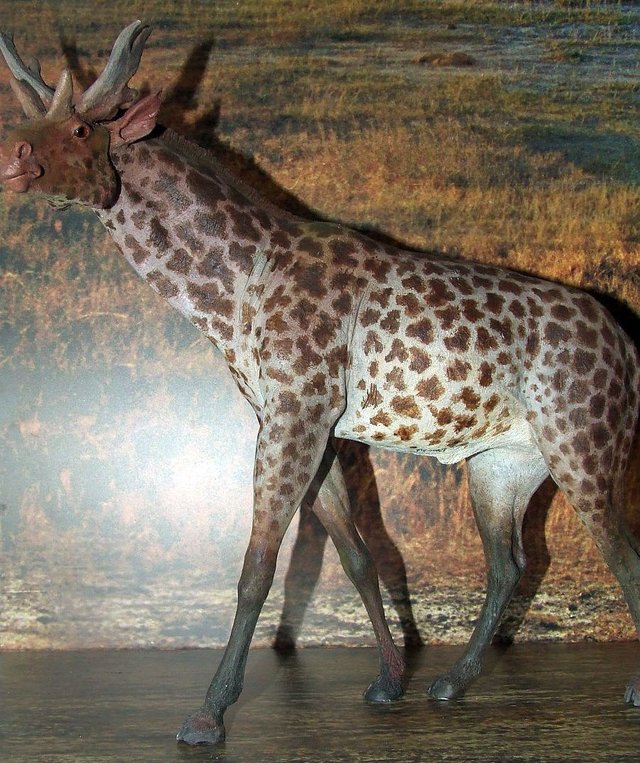

- Sivatherium: Museum of Evolution of Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw, © Hiuppo (photographer), Creative Commons License

- Siwalik Sandstone Complex: Siwalik Sandstone Complex, Jawalamukhi, Himachal Pradesh, India, © Peter Clift (photographer), Louisiana State University, Department of Geology & Geophysics, Creative Commons License

- Petrified Wood from the Siwalik Hills: Shivalik Fossil Park, Himachal Pradesh, India, © Khursheed Dinshaw (photographer), Fair Use