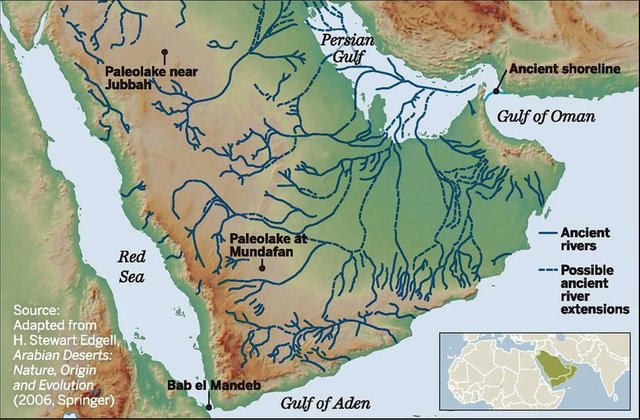

In the second section of Chapter VII of Earth in Upheaval, Immanuel Velikovsky turns from the Sahara to another desert that has recently undergone a similar metamorphosis: the Arabian Desert. Today, Saudi Arabia is the largest country in the World with no rivers. There are, in fact, no permanent rivers anywhere within the Arabian Peninsula. But this was not always the case:

There is a “certainty beyond challenge that when the icecap of the last Glacial period covered a large part of the northern hemisphere, at least three great rivers flowed from west to east across the whole width of the [Arabian] Peninsula.” So wrote Philby in his book Arabia. There was also a large lake in Arabia that disappeared in some geological or climatal change. (Velikovsky 88)

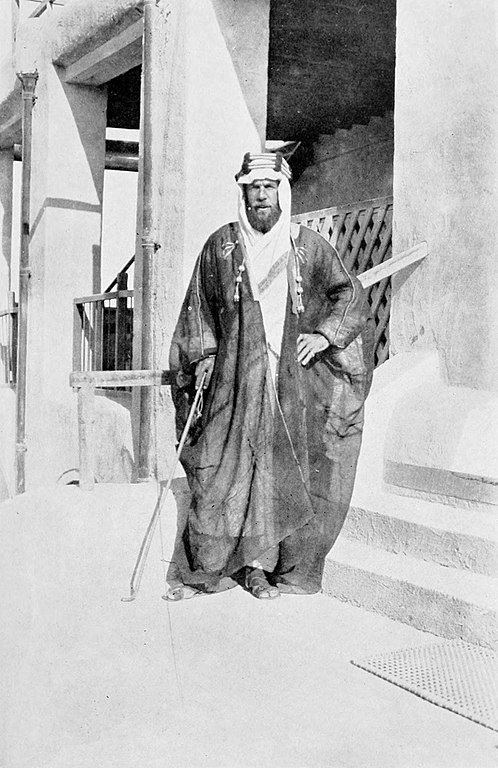

Harry St John Bridger Philby was a British intelligence officer and explorer. He is perhaps best known today as the father of Kim Philby, the Cold War spy. In November 1917 he took part in a diplomatic mission to Ibn Saud, ruler of the Nejd in central Arabia, to gain his support for the Arab Revolt against the Ottoman Turks. He journeyed by camel from the Persian Gulf to Riyadh, where he spent ten days in the company of Ibn Saud. From Riyadh he continued west to Jeddah on the Red Sea. This crossing of the Arabian Peninsula from coast to coast brought him to the attention of the general public. In 1930 he published an account of the recent history of the Peninsula under the title Arabia. It is from the introduction to this book that Velikovsky’s first quotation comes:

Without trespassing on the domain of Palaeontology or probing too intimately the interesting problem of the scene of man’s first beginnings on earth, it may be assumed with some confidence that Arabia figured more prominently in the international scheme of Neanderthal man and of the first ancestors of Homo sapiens than it has ever—with one brief but brilliant exception—done in Christian times up to the epoch of the Great War. Doubtless there was a complete absence of political consciousness in the world during those halcyon days when Arabia was really “Felix,” but the marks of to-day indicate with a certainty beyond challenge that when the ice-cap of the last Glacial period covered a large part of the northern hemisphere, at least three great rivers flowed from west to east across the whole width of the peninsula. In fact, Arabia, now a desert conforming closely to type, was then a habitable country. The retreat of the ice, and the Pluvial periods following thereon, were succeeded by a process of desiccation which has to our own times maintained its terrible sway over vast areas of the earth’s central belt, creating deserts in place of forests and pasture-lands, and driving their animal occupants, including man, north and south to more tenable abodes. (Philby xv)

Velikovsky’s source for both this quotation and the second concerning the large lake, however, was a footnote in Christina Phelps Grant’s The Syrian Desert of 1937:

The principal argument advanced to prove a genuine change of climate in the Syrian Desert are as follows: (a) Numerous authorities have agreed on the former, relatively greater fertility of Palmyrena. (b) Mr H. St. J. B. Philby and Major A. L. Holt agree that there must have been more rainfall in the Great Desert, at least in the Roman period, than there is, on the average, today. For one thing, the line of cultivation in Trans-Jordan extended further east than it now does. For another, the numerous hunting-boxes of the Omayyad Caliphs prove that game was abundant in the seventh and eighth centuries A.D., where now no animals are to be found. Lastly, at el-Jidd, in the near neighbourhood of Jebel Anaza (i.e. in the central Hamad), are the remains of habitations; building-stones, weighing more than two tons, have obviously been carried for some distances, and two water-holes have been cut through 160 feet of limestone. (c) Mr Philby, writing of Arabia, states that there is a “certainty beyond challenge that when the ice-cap of the last Glacial period covered a large part of the northern hemisphere, at least three great rivers flowed from west to east across the whole width of the peninsula” (H. St. B. Philby, Arabia (1930), p. xv).

The discovery by Mr Bertram Thomas of the evidences of a dried-up lake in Arabia tends to substantiate this statement. And these theories and proofs of climatic change in Arabia have convinced various students of the Syrian Desert that analogous changes have also taken place there. (Grant 53, fn 1)

Christina Phelps Grant was an American historian who specialized in the study of the Middle East. In the 1930s she travelled extensively throughout the region. A record of her experiences, The Syrian Desert, was published in 1937.

Like Philby, Bertram Sidney Thomas became acquainted with the Middle East when he was serving as a British diplomat during World War I. It was in the 1920s and ’30s, however, when he was Finance Minister to the Sultan of Muscat and Oman (now Oman), that he undertook several expeditions into the Empty Quarter of the Arabian Desert. His account of these travels was published in 1932 under the title Arabia Felix:

My attention was suddenly arrested by the phenomenon of silver patches in the low troughs, looking from a distance like sheets of ice or the salt residues of dried-up lakes. Such ghadhera—they proved to be gypsum—appeared with growing frequency throughout these dunes of Yibaila and Yadila and two days later in the sand mountains of Uruq-adh-Dhahiya. (Thomas 164)

Salt flats are not uncommon in the Arabian Desert. Recently, satellite images have revealed the extent of the Peninsula’s former waterways:

Satellite images have revealed that a network of ancient rivers once coursed their way through the sand of the Arabian Desert, leading scientists to believe that the region experienced wetter periods in the past. (University of Oxford)

One study reveals that the Peninsula may once have been home to thousands of lakes:

These data also have implications at the peninsula level. Palaeoprecipitation models suggest the extent of increased rainfall during interglacials ... and an increasing body of palaeoenvironmental records, coupled with our palaeohydrological reconstruction and modelling indicates that during humid episodes potentially thousands of water bodies may have existed across areas of the Arabian interior, expanding favourable biogeographic zones and facilitating the expansion of mammalian populations. This confirms early work by researchers such as McClure, who hypothesised that several thousand water bodies, ranging from ephemeral ponds to large freshwater lakes were scattered across Arabia. (Breeze et al 115)

Volcanism or Meteoritics

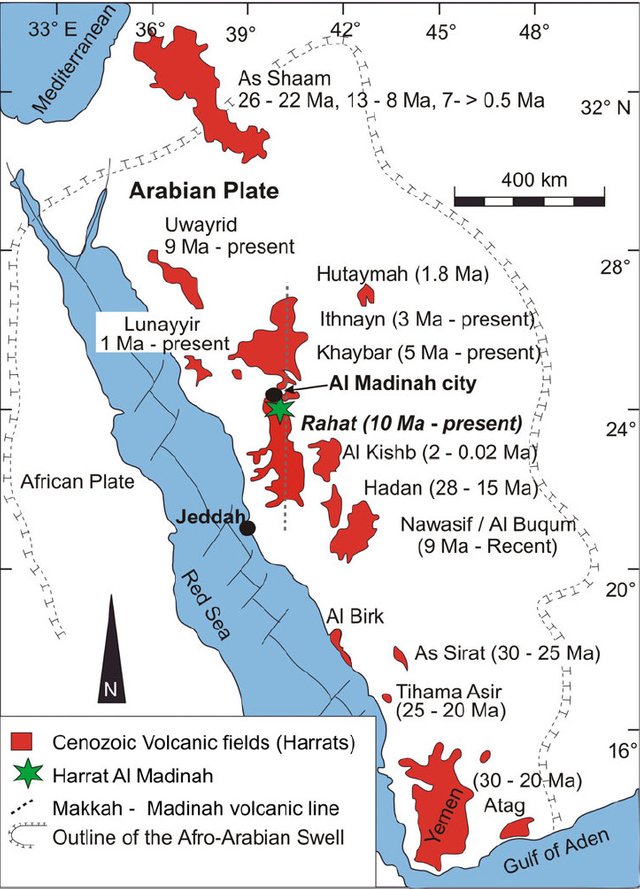

The Arabian Peninsula comprises a minor tectonic plate wedged between five other plates. Ringed as it is by active plate boundaries, it is not surprising to find that it has been subjected to regular intervals of volcanism, though only about nine volcanoes are thought to have been active during the Holocene:

| Volcano | Location | Last Eruption |

|---|---|---|

| Harrat al-Sham | Syria-Jordan-Saudi Arabia | 2670 BCE |

| Harrat al Birk | SW Saudi Arabia | Holocene |

| Harrat ar Rahah | NW Saudi Arabia | Holocene |

| Harrat Ithnayn | NW Saudi Arabia | Holocene |

| Harrat Khaybar | NW Saudi Arabia | 600-700 CE |

| Harrat Kishb | W Central Saudi Arabia | Holocene |

| Harrat Lunayyir | NW Saudi Arabia | 1000 CE |

| Harrat Rahat | Saudi Arabia | 1256 CE |

| Harrat ar Rahah-‛Uwayrid | NW Saudi Arabia | 640 |

| Jabal Yar | Saudi Arabia | 1800-1820 CE |

Velikovsky cites B Moritz to the effect that the last eruption took place in 1253. Bernhard Moritz was a German librarian who worked as a research assistant in the Egyptian department of the Berlin State Museums. In 1887 he accompanied Robert Koldewey to Mesopotamia to undertake preliminary excavations of the Sumerian cities of Nina (Surghul) and Lagaš (El-Hiba). In the same year Moritz joined the newly established Department of Oriental Languages (Seminar für Orientalische Sprachen) in Berlin, where he worked for ten years as acting secretary, librarian and teacher of Arabic. Among his work for the Seminar was Arabien: Studien zur Physikalischen und Historischen Geographie des Landes [Arabia: Studies in the Physical and Historical Geography of the Country], which was published in 1923:

Dann kam 1253 ein großer Ausbruch bei ‘Aden. Seit dieser Zeit scheint die vulkanische Tätigkeit in Arabien zur Ruhe gekommen zu sein; aktive Vulkane gibt es in dem ganzen Lande wohl keine mehr. Nur in Hismā soll ein Berg ‘Alandā noch im zehnten Jahrhundert ständig Rauch ausgestoßen haben.

Then in 1253 there was a major eruption at Aden. Since that time volcanic activity in Arabia seems to have died down; there are probably no more active volcanoes in the whole country. Only in Hisma is Mount ‛Aland said to have been constantly emitting smoke as late as the tenth century. (Moritz 14)

Moritz’s source for the date 1253 is the Concise History of Humanity by Abulfeda, a Damascene geographer and historian, who flourished in the early decades of the 14th century. Abulfeda’s entry for the year 1253 CE concludes with the following notice (in Johann Jakob Reiske’s Latin translation):

Fama ferebat eodem anno Mecca veniens, circa Adanam [in Arabia felice] et aliquos vicinorum montium, conspectos fuisse ignes, noctu quidem manifestos et luculentos, interdiu autem fumum ingentem exhalantes.

In the same year a rumour coming to Mecca reported that fires had been observed around Adana [in Arabia Felix] and some of the neighboring mountains, which were indeed clear and bright at night, but emitted a huge smoke during the day. (Abulfeda 1253 CE, Reiske 533)

Harrat Rahat, which last erupted in 1256, is nowhere near Aden. In fact, none of Arabia’s Holocene volcanoes is close to Aden. As Moritz points out in a footnote, the reference to Mount ‛Alandā is probably an error, and actually refers to a smoking bush (Moritz 14 fn 4).

The date of 1256 for the last eruption of Harrat Rahat is based on another Arabic text, the Wafa Al-Wafa, which was written in 1568 (Camp et al 491).

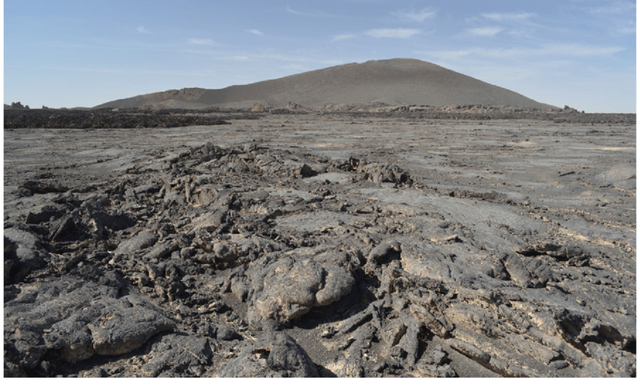

Velikovsky questions whether the so-called harras of Arabia are volcanic fields:

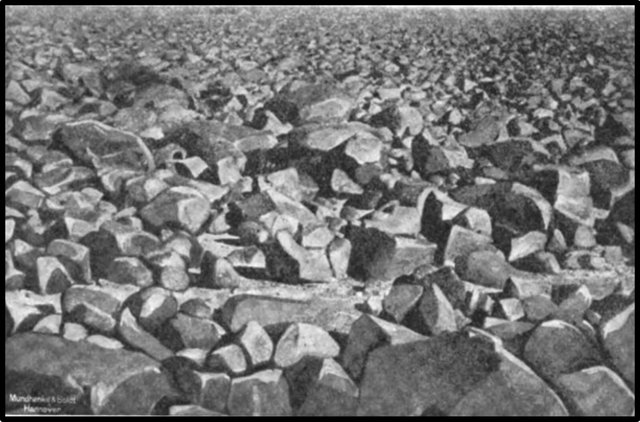

Twenty-eight fields of burned and broken stones, called “harras”, are found in Arabia, mostly in the western half of the great desert. Some single fields are one hundred miles [160 km] in diameter and occupy an area of six or seven thousand square miles [15-18,000 km2], stone lying close to stone, so densely packed that passage through the field is almost impossible. The stones are sharp-edged and scorched black. No volcanic eruption could have cast scorched stones over fields as large as the harras; neither would the stones from volcanoes have been so evenly spread. The absence, in most cases, of lava—the stones lie free—also speaks against a volcanic origin of the stones. (Velikovsky 88-89)

Velikovsky source for these harras (or harrats) are C M Doughty and Moritz’s Arabien. Charles Montagu Doughty was an English writer and explorer of the late 19th century. He is best known for Travels in Arabia Deserta, a work so eccentric it was parodied by James Joyce in Finnegans Wake. Velikovsky does not actually name this work or cite any particular page. It appears that he came across Doughty’s name in the following passage in Moritz:

Solcher vulkanischen Gebiete kannten die Araber in Nord- und Zentral-Arabien 28. Fast sämtlich liegen sie in der westlichen Hälfte der Halbinsel ... Dieses Gebiet, das eine nordsüdliche Ausdehnung von etwa 150 km hat, ist bis jetzt einigermaßen bekannt geworden, wenn schon seine Grenze im Osten sich noch nicht hat genau feststellen lassen ... Sie ist durch Doughty bekannt geworden, der ihr eine sehr frühe Entstehung zuschreibt (I 419). Noch westlicher und an der Küste des Roten Meeres nordwestlich von Jembo liegt die kleine Harrat er Rifa', von der Bau- und Mühlsteine geholt werden.

The Arabs in northern and central Arabia were familiar with 28 such volcanic regions. Almost all of them are in the western half of the peninsula ... This area, which has a north-south extent of about 150 km, has become fairly well known, even if its boundary to the east has not yet been precisely determined ... It became known through Doughty, who ascribes a very early origin to it (I 419). Still further west and on the Red Sea coast northwest of Jembo is the little Harrat er Rifa’, from which building stones and millstones are quarried. (Moritz 12)

The reference to Doughty (I 419) reads as follows:

Viewing the great thickness of lava floods, we can imagine the very old beginning of the Harra,—those streams upon streams of basalt, which appear in the walls of some wady-breaches of the desolate Aueyrid [Harrat ‛Uwayrid]. (Doughty 419)

In a footnote, Velikovsky mentions that Arabien contains a close-up photograph of a harra:

Velikovsky theorizes that these harras are of meteoritic origin:

It appears that the blackened and broken stones of the harras are trains of meteorites, scorched in their passage through the atmosphere, that broke during their fall, as bolides do, or on reaching the ground. Billions of stones in a single harra indicate that the trains of meteorites were very large and can be classed as comets. Despite alternate exposure to the thermal action of the hot desert sun and the cool desert night, the sharp edges of the stones have been preserved, which shows that they fell in a not too distant period of time. (Velikovsky 89)

The consensus among modern geologists is that the harras of Arabia are volcanic fields of quaternary age. Nevertheless, it can hardly be denied that some harrats resemble fields of stones while others resemble flows of lava

Jabal Maqla

In the northwest of the Arabian Peninsula there is a mountain with a distinctive black peak, which is known as the Burnt Mountain, Jabal Maqla. Except for the characteristic cap of black rock, the mountain is of a light brown colour. A number of Biblical scholars have hypothesized that this is the Holy Mount of the Exodus, referred to in the Pentateuch as Mount Horeb and Mount Sinai, and described variously as the Mountain of Elohim and the Mountain of Yahweh. According to these theorists, the blackened peak is evidence of the miraculous events described in Exodus:

And it came to pass on the third day in the morning, that there were thunders and lightnings, and a thick cloud upon the mount, and the voice of the trumpet exceeding loud; so that all the people that was in the camp trembled. And Moses brought forth the people out of the camp to meet with God; and they stood at the nether part of the mount. And mount Sinai was altogether on a smoke, because the Lord descended upon it in fire: and the smoke thereof ascended as the smoke of a furnace, and the whole mount quaked greatly. (Exodus 19:16-18)

There seems to be some confusion in the literature over the identity of this mountain. Several theorists refer to it as Jabal al-Lawz, another mountain that lies about 7 km to the north of Jabal Maqla. Penny and Jim Caldwell distinguish the two peaks, identifying al-Lawz as Mount Horeb and Maqla as Mount Sinai (Whittaker 82-83 fn 172)

One of the first to suggest that Mount Sinai was in Arabia was the English traveller Charles Tilstone Beke. Beke theorized that Mount Sinai was a volcano—Velikovsky actually cites his pamphlet Mount Sinai a Volcano in Worlds in Collision and Ages in Chaos—but when he failed to identify any volcanoes in the Sinai Peninsula, Beke turned his attention to northwestern Arabia, which had several potential candidates. He decided that the Biblical toponyms Mount Horeb and Mount Sinai referred to two volcanic peaks in the southwest of Jordan: Jabal Ahmad al Baqir and Jebel Ertowa respectively (Whittaker 71-72).

The mountain range to which Jabal al-Lawz and Jabal Maqla belong is of igneous origin, but these peaks are not volcanoes.

In 2003, Baptist pastor Charles Whittaker of Louisiana Baptist University made the Burnt Mountain and its environs the subject of his doctoral dissertation:

According to eyewitnesses, when one stands upon the top of Jabal al Lawz and looks in all directions, there is a common brown/gray cast of granite as far as the eye can see in the mountains. This blanket of granite, however, is interrupted abruptly with the dark rock on the peak of Maqla. Its lone distinctiveness makes one wonder why it is so isolated. (Whittaker 121-122)

Whittaker consulted three geologists regarding the analysis of a rock from Jabal Maqla made by Nehru E Cherukupalli PhD, Department Chairman at Brooklyn College and Research Associate at the American Museum of Natural History. Cherukupalli’s unabridged analysis reads:

Rock description: a very fine grained greenish looking rock. Could not identify much in it. After studying the polished thin section of the rock it is given the name amphibolite: The rock is fine grained and is crystalline. Amphibole (actinolitic type), bluish green in color along with some chlorite and possible albitic plagioclase feldspar make up the rock. There are a few accessory minerals like opaque iron oxides. The rock is metamorphosed in the low to middle amphibolite facies and may have undergone metamorphism at an approximate temperature of 500 degrees or lower at low pressure, no more than 2 to 3 kilobars. My guess is that the rock started out as an igneous rock, probably of basaltic or andesitic composition and was later metamorphosed. It is not possible to determine the age of the rock without knowing the geology of the region from which it was collected. (Whittaker 125 fn 262)

It appears that the peak of Jabal Maqla is comprised of two different types of rock:

The rocks on the peak of Maqla [black peak] are comprised of two different types. The one Jim [Caldwell] called greenstone [a geologist friend labeled it such] is an extremely hard and dense smooth stone, a very dark bluish-gray-black in appearance. It is equally distributed among the entire upper region of Maqla. The other rock is darkened to the point of appearing black. It is absolutely granite, of the exact same variety of the entire rest of the mountains in the area. It appears reddish-pinkish-brown on all the surrounding mountains. The difference in this peaks dispersion of this rock is that it has been darkened. By what, I don’t know. It is much softer in texture than the greenstone. (Whittaker 124, quoting Penny Cox Caldwell, who had also consulted a geologist)

Whittaker found that while all three geologists he consulted agreed that the blackening of the peak was a natural phenomenon, they were unable to give a complete explanation without visiting the mountain and conducting an on-site investigation:

There could be several explanations for the black top of greenstone and blackened granite. One idea may be that the basalt intruded up toward the surface rock and then metamorphosed the rock around the intrusion into the greenstone under the surface and then erosion over many years exposed the greenstone. Another idea may be that the granite was intruded or flowed into the greenstone and some greenstone was left on top. This could be a basalt dyke covered with greenstone. The long weathering process could attest to the intermingled blackened boulders/rocks on the site. When asked if it was typical of intrusions, flows or dykes to produce such an abrupt line of division between two kinds of rock as this mountain does, the professors responded in the affirmative. When one postulates that perhaps the Lord came down on the mountain, and by the intense heat metamorphosed the granite into greenstone, there are some problems with that idea. One concern is that the granite of Maqla is not the parent rock of the black portion or amphibolite. Turning granite into greenstone regardless of heat would have required a large amount of iron to be present in the greenstone. This was not the case with the sample. According to the geologists, the greenstone was metamorphosed at a low temperature with very little iron content. Lighter colored rock is not the parent of the darker rock because the light rock does not have the chemical ingredients to develop into the dark rock. They also make the point that metamorphous granite is not dark, as it is full of quartz (Whittaker 126)

Bearing in mind the fact that Jabal Maqla is the only peak in this mountain range to have experienced this strange blackening, I find it hard to disagree with Whittaker’s conclusion:

The fact remains that there are some questions about explaining the black top of Maqla in completely natural terms. The fact of such isolated weathering on just one peak on the granite rocks, fosters questions that may only be answered by an on-site analysis. However, it may be concluded that one might explain this feature as a natural phenomenon. (Whittaker 131)

Velikovsky would probably have sought a natural origin for the blackened peak, albeit a celestial one. But he does not seem to have been aware of its existence, as it is never mentioned in his discussion of the Arabian harras. Researchers from the Doubting Thomas Research Foundation believe that the discovery of what appear to be Proto-Hebrew inscriptions in the vicinity of Jabal Maqla support their claim that this is the Biblical Mount Sinai. Their discoveries certainly merit further study.

Wobar

Velikovsky is on firmer ground when he discusses the Wabar craters:

Larger bodies than the stones of the harras fell on Arabia, too. In Wobar in the desert there is a meteoric crater with meteoric iron and silica glass spread around it. (Velikovsky 89)

He cites two sources:

R Schwinner, Physikalische Geologie (1936), I, 114, 163

L J Spencer, “Meteoric Iron and Silica Glass from the Craters of Henbury (Central Australia) and Wobar [sic] (Arabia),” Mineralogical Magazine, XXIII (1933), 387-404.

Robert Schwinner was an Austrian geologist and geophysicist. Between 1923 and his retirement in 1946 he was Associate Professor of Physical Geology at the Institute for Geology and Palaeontology at the University of Graz. He contributed to the study of plate tectonics during its pioneering days. Curiously, Alfred Wegener, the father of plate tectonics, taught at Graz at the same time as Schwinner, but the two men never worked together.

He planned to publish a three-volume textbook on physical geology, but only the first volume appeared in 1936 under the title Lehrbuch der physikalischen Geologie [Textbook of Physical Geology]. The manuscript of Volume 2 was found in the Geological Institute in 2007 and subsequently published.

Leonard James Spencer was a British geologist who specialized in the field of mineralogy. He was president of the Mineralogical Society of Great Britain and Ireland from 1936 to 1939, and contributed at least 146 articles to the Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh Edition, 1911).

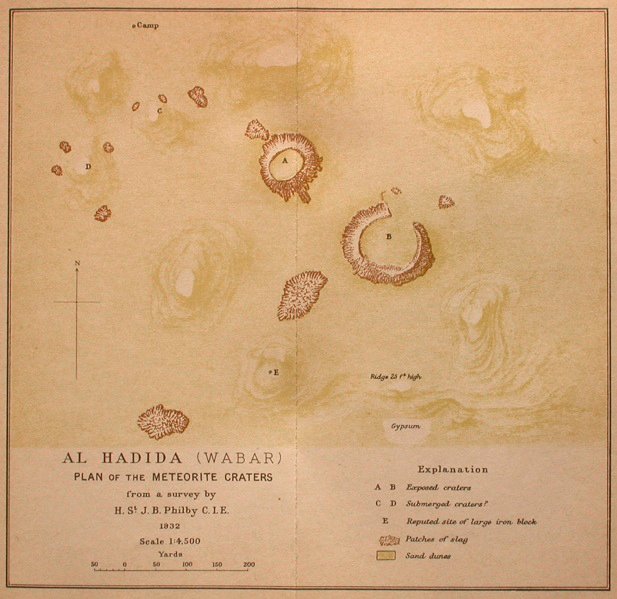

Velikovsky speaks of a meteoric crater in Wobar. Spencer calls the place Wabar and correctly refers to craters, as there are at least three impact craters at the site—and possibly as many as five, though the continual shifting of the sand makes identification difficult:

Wabar Craters, group of meteorite craters discovered in 1932 in the Rubʿ al-Khalī desert of Saudi Arabia. The largest crater is 330 feet (100 m) in diameter, 40 feet (12 m) deep, partially filled with sand, and thought to be an explosion crater (formed from an explosion on impact). A crater located 0.6 mile (1 km) northwest is about half the size of the main crater and is thought to be two partially superimposed craters. Two others in the area are completely filled with sand. Fused silica glass and tiny globules of nickel-iron have been found near the main crater. (Britannica)

The Wabar Craters are now believed to have been formed by meteoritic impacts that occurred only a few centuries ago. A fireball observed in Tarim, Yemen, on 1 September 1704 and mentioned in two historical poems has been identified as the Wabar impact event, though a more recent date of 1863 has also been proposed (Gnos et al 2001, 2012).

Velikovsky may have taken his details from Schwinner, but I cannot confirm this as I have not yet found a copy of his Lehrbuch der physikalischen Geologie online. In the title of his paper, Spencer calls the place Wabar, though Velikovsky has Wobar. I am guessing that Schwinner mistakenly wrote Wobar when he cited Spencer, and Velikovsky did not trouble himself to look up Spencer’s paper.

Lost Cities

Velikovsky next turns to the possibility that civilizations once flourished in Arabia where now there is only uninhabitable desert:

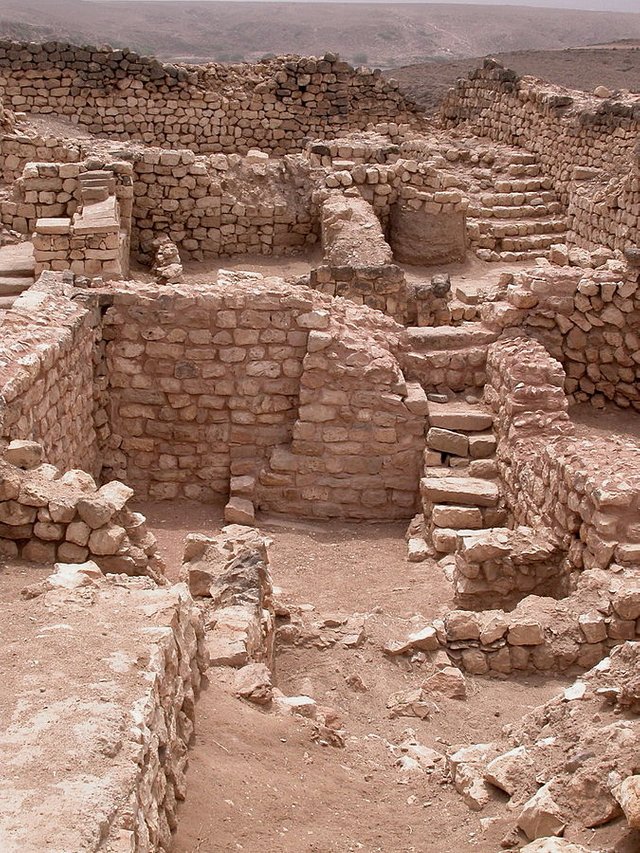

In the southern part of the great Arabian desert, ancient ruins, almost entirely obliterated by time and the elements, and vestiges of cultivation are silent witnesses of the time when the land there was hospitable and fruitful; it was as copiously watered and luxuriously forested as India on the same latitude. Orchards covered Hadhramaut and Aden. It was a land of plenty, paradise on earth, but following a sudden catastrophe, Arabia Felix turned to a barren land. Arabia Petraea, the western part of the desert, is a dusty rock of lava that is broken by the Great Rift, with the Dead Sea, an inner lake, on its bottom. Sulphurous springs flow into it, and asphalt rises from its floor and floats on it. (Velikovsky 90)

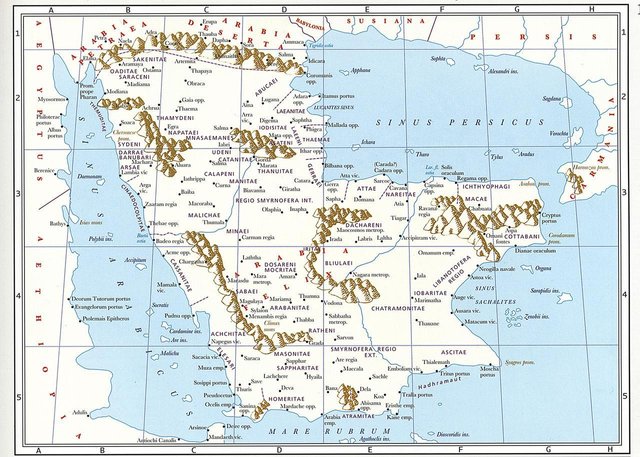

Today, it is claimed that the Roman name Arabia Felix [Happy Arabia]—or, in Greek, Εὐδαίμων Ἀραβία (Eudaimōn Arabia)—simply refers to the fact that southern Arabia was more fertile than the rest of the peninsula, which was called Arabia Deserta. The Roman province of Arabia Petraea (Rocky Arabia) comprised the Sinai Peninsula and the Biblical territories of Midian, Edom, Moab and Ammon. But was Arabia Felix still a fertile and watered land in early historical times? The so-called Empty Quarter, or Rub’ al Khali, lies in Arabia Felix, though it is now an almost unbroken expanse of sand, with so little annual precipitation that its climate is classified as hyperarid.

St John Philby, the explorer who brought the existence of the Wabar Craters to the attention of the scientific community, was searching for the lost city of Wabar—identified with the city of Iram in the Quran 89—in the Empty Quarter when he came across them:

Last year Mr. Thomas was shown the “road to Ubar,” and was told of what he took to be columns, also of a mysterious piece of iron ... On the evidence so gathered I had come to the conclusion that there were two localities in question—a locality with the ruins of ancient human habitations and another with a strange large block of iron described to me as being about as large as a camel ... The name Al Hahida was applied to the iron and rather vaguely also to the ruins ... The name Wabar comes from the semi-classical legend and is applied to these ruins in the Empty Quarter by the town-dwellers on its fringes ... (Philby 1933:12)

To this brief account Spencer adds some useful details:

Hadid is the Arabic name for iron, and Al Hadida, i.e. place of the iron, is identified by Mr. Philby with the site of the legendary city of Wabar, mentioned in semi-classical Arabian writings as having been ‛destroyed by fire from heaven’. The ‛ruins’ are the meteorite craters and the ‛cinders’ the abundant silica-glass. This spot is at 21° 29½ ' N., 50° 40' E. From information given to Mr. Bertram Thomas, during his journey across the Rub’ al Khali in 1931, he provisionally placed the legendary city of ‛Ubar’ on his map at about 19° N., 52½° E. Farther north he passed within ten miles of the meteorite craters, but unfortunately missed them, and Mr. Philby is the only European who has visited the spot. The identity and location of ‛Wabar’ or ‛Ubar’ or ‛Obar’ (or ‛Ophir’) are, in fact, still matters for discussion. (Spencer 402)

The assumption that Al Hadida, Place of the Iron, was that of the lost city of Ubar—based on the belief that the iron referred to man-made artifacts—fell apart when it was discovered that the iron in question was of meteoritic origin. The situation is further complicated by the nomenclature. The common notion that Ubar and Iram are two different names of the same city is fallacious:

There’s a lot of confusion about that word [Ubar]. If you look at the classical texts and the Arab historical sources, Ubar refers to a region and a group of people, not to a specific town. People always overlook that. It’s very clear on Ptolemy’s second century map of the area. It says in big letters “Iobaritae” [Ἰωβαρῖται or Ἰοβαρῖται]. And in his text that accompanied the maps, he’s very clear about that. It was only the late medieval version of One Thousand and One Nights, in the fourteenth or fifteenth century, that romanticised Ubar and turned it into a city, rather than a region or a people. (Juris Zarins)

In Ptolemy’s Geography, the Ἰωβαρῖται or Ἰοβαρῖται are mentioned in Book 6, Chapter 7 (Arabia Felix, Sixth Map of Asia), § 24, line 26, where they are said to be next to the Σαχαλῖται (Sachalitae or Sachalites) (Nobbe 103).

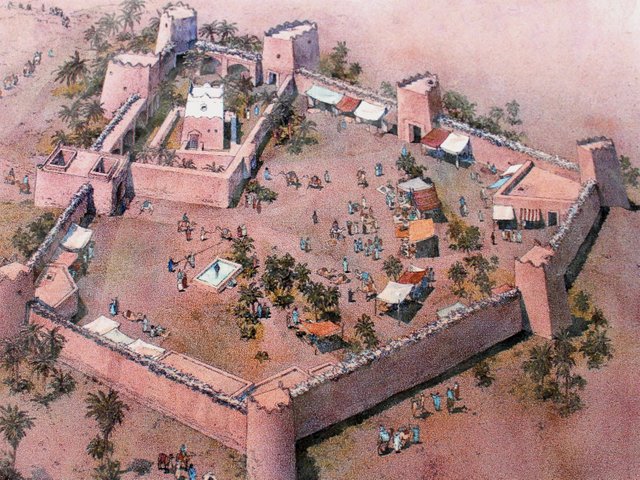

In November 1991 the remains of an abandoned city were discovered about 400 km southeast of the Wabar Craters in Oman. Scholars remain divided over whether or not this is the site of the lost city of Iram:

This we finally believed was Ubar ... Key to that match were:

LOCATION The site was where it was supposed to be. The myth of Ubar had led us to the unremitting desolation of a remote area of Arabia—and, against all expectation, an impressive fortress.

AGE The site was ancient. In myth, Ubar was founded by Noah’s grandson, a first patriarch of the People of ’Ad. What we have found dated to 900 B.C. or earlier—the very dawn of civilization in this land. Our site was among the oldest, if not the oldest, of Arabia’s incense-trading caravansaries.

CHARACTER Here was an expression of the Koran’s ذَات ٱلْعِمَاد, dhat al-imad, city of lofty buildings. And Ubar’s eight or more towers guarded a water source that, more than anything else in the surrounding fifty thousand square miles, qualified as “the great well of Wabar” described by the historian Yaqut ibn Abdullah as the city’s principal feature. For all its isolation, here was a place where, as in its legend, people prospered and lived well, cooking and dining on the ware of classical civilizations.

DESTRUCTION The legend of Ubar climaxed as the city “sank into the sands.” It surely did. Ubar wasn’t burned and sacked, decimated by plague, or rocked by deadly quake. It collapsed into an underground cavern. Of all the sites in all the ancient world, Ubar came to a unique and peculiar end, an end identical in legend and reality. (Clapp 201 ...202-203)

The sands of Arabia must conceal many more secrets. In 2022 a group of Arabian and French archaeologists discovered a settlement thought to be 8,000 years old, adjacent to the historic site of Qaryat al-Faw.

Other Deserts

Velikovsky concludes this section by briefly mentioning a few other barren deserts in which similar ruins are found:

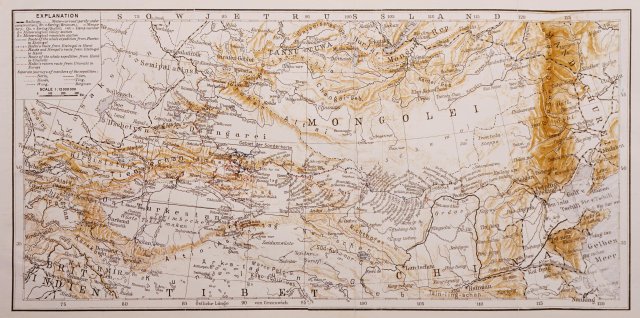

Like the Sahara and Arabian deserts, other great deserts of the world disclose the fact that they were inhabited and cultivated sometime in the past. On the Tibetan plateau and in the Gobi Desert remains of early prosperous civilizations were found with occasional ruins surviving from those times when the great barren tracts were cultivated. In the Gobi Desert, as in the Arabian and Sahara deserts, the impression is gained that in a tectonic disturbance the subterranean water dropped to a great depth, the sources became sealed, and the rivers dried up completely. Some changes in ground structure or in ground currents also affect the clouds, which pass over such lands without unburdening themselves. (Velikovsky 90)

No sources are cited for any of this, but it is correct. In the barren wastes of the Gobi Desert there are indeed the ruins of abandoned cities, though some of these were only abandoned a few centuries ago:

In 1876, the Anglo-Indian diplomat Thomas Douglas Forsyth read a paper On the Buried Cities in the Shifting Sands of the Great Desert of Gobi at a meeting of the Royal Geographical Society in London:

Among the many objects of interest which attracted our attention, during the late Mission to Kashghar, not the least interesting was an inquiry regarding the shifting sands of the Great Desert of Gobi, and the reported existence of ancient cities which had been buried in the sands ages ago, and which are now gradually coming to light ...

The 36th and three following chapters [of The Travels of Marco Polo] refer to the country in which we are at present interested. His chapter on Khotan is provokingly meagre, for there is very great interest attaching to this place. It is supposed by some that this city was the limit of Darius’s conquest. I have several Greek and Byzantine coins which were found in the ruins of the city near Kiria ...

The 37th chapter of Marco Polo relates to Pein, and it is evident that at that time the city called by that name was in existence. From the geographical description given by Colonel Yule in his valuable notes on this chapter, I should say that Pein or Pima must be identical with Kiria ...

As regards Charchan, or Charchand, we got some information from persons who had been there. It is a place of some importance and was used as a penal settlement by the Chinese, and is now held by a Governor under the Ameer of Kashghar. It contains about 500 houses, situated on the banks of two rivers, which unite on the plain and flow to Lake Lop. The town is situated at the foot of a mountain to the south, and the river which flows by it is said to from Tibet ...

One thing strikes me as remarkable, that though, as I suppose, Marco Polo visited Khotan, and passed along the road to Lop, he nowhere mentions the report of buried cities being in existence. Mirza Haidar, writing two centuries afterwards, alludes to them; and we learn from Chinese authorities that they were known to have been buried many centuries before Marco Polo’s time ...

Mirza Haidar gives an account of the destruction of this city of Katak. According to him, the fate of the city had long been foreseen in the gradual advance of the sand ...

But a similar tale is told by the Chinese of another town, at or near Pima, which was destroyed in a somewhat similar manner in the sixth century a.d. ...

... it appears that the large town of Lop, mentioned by Marco Polo, exists no longer ...

According to information we picked up from travellers, and confirmed by Syad Yakub Khan, there is a ruined city called Tukht-i-Turan, close to the city of Kuchar, on a hill of bare rock; the ruins are of earth of a deep yellow colour, quite unlike anything on the hill; there are besides a large number of caves, excavated for residence. The city is said to have existed previous to the first Chinese occupation, and to have been consumed by fire owing to the refusal of its ruler to adopt the Mahommedan faith ...

Some very remarkable ruins are said to exist not far from Mural Bashi ...

Not far from the present city of Kashghar is the Kohna Shahr, or old city, which was destroyed many centuries ago, yet the walls, though only built of sun-dried bricks, are standing, with the holes in which the rafters were Inserted as clearly defined as if they had been only just used ... (Forsyth 27-39)

Forsyth believed that these cities were abandoned after they were buried by sand blown in from the northwestern reaches of the Gobi, or from Siberia, or from the Tian Shan mountain range in Central Asia (Forsyth 39-40).

Tibet, too, is home to the ruins of several extinct civilizations:

In the inhospitable Taklamakan Desert, which lies in the northwestern Chinese province of Xinjiang, there are also ruined cities that testify to the former fertility of the region. The best known is Gaochang, built by the Jushi people in the 1st century BCE. The city was finally abandoned around 1400 after the Mongols conquered Xijiang. Its ruins now stand in a sparsely-populated and desolate landscape.

The Lop Desert in Xijiang is an eastern extension of the Taklamakan. It was home to the ancient Loulan Kingdom, or Kroraina, which flourished between 200 BCE and the 4th century of the Common Era (Whitfield 169 ff). The ruins of several of its cities—eg Niya, Charklik, Miran—are now surrounded by the desert.

And that’s a good place to stop.

References

- Charles Beke, Mount Sinai, a Volcano, Tinsley Brothers (1873)

- Paul S Breeze et al, Remote Sensing and GIS Techniques for Reconstructing Arabian Palaeohydrology and Identifying Archaeological Sites, Quaternary International, Volume 382, Pages 98-119, Elsevier, Amsterdam (2015)

- Jim & Penny Caldwell, The Real Mount Sinai, Split Rock Research Foundation, Diamondhead, Mississippi (2011)

- Victor E Camp et al, The Madinah Eruption, Saudi Arabia: Magma Mixing and Simultaneous Extrusion of Three Basaltic Chemical Types, Bulletin of Volcanology, Volume 49, Number 2, Pages 489-508, Springer-Verlag, Berlin (1987)

- Nicholas Clapp, The Road to Ubar: Finding the Atlantis of the Sands, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston (1999)

- Charles Montagu Doughty, Travels in Arabia Deserta, Philip Lee Warner, The Medici Society, Ltd, London (1921)

- Thomas Douglas Forsyth, On the Buried Cities in the Shifting Sands of the Great Desert of Gobi, Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society, Volume 21, Number 1, Pages 27-46, The Royal Geographical Society, London (1877)

- E Gnos et al, The Wabar Impact Craters, Saudi Arabia, Revisited, Meteoritics and Planetary Science, Volume 48, Issue 10, Pages 2000-2014, The Meteoritical Society, Wiley-Blackwell, Hoboken, New Jersey (2013)

- Christina Phelps Grant, The Syrian Desert: Caravans, Travel and Exploration, A & C Black Ltd, London (1937)

- Bernhard Moritz, Arabien: Studien zur Physikalischen und Historischen Geographie des Landes, Orient Buch-Handlung Heinz Lafaire, Hannover (1923)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe (editor), Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 2, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Harry St John Bridger Philby, Arabia, Ernest Benn Limited, London (1930)

- Harry St John Bridger Philby, Rub’ al Khali: An Account of Exploration in the Great Desert of Arabia under the Auspices and Patronage of His Majesty ‛Abdul ‛Aziz ibn Sa’ud, King of the Hejaz and Nejd and its Dependencies, The Geographical Journal, Volume 81, Number 1, Pages 1-21, Royal Geographical Society, London (1933)

- Johann Jakob Reiske, Abulfedae Annales Muslemici Arabice et Latine, Volume 4, Friedrich Wilhelm Thiele, Copenhagen (1792)

- Robert Schwinner, Physikalische Geologie, Volume 1 [The Earth as a Celestial Body : Astronomy, Geophysics, Geology and Their Interrelationships], Gebrüder Borntraeger, Berlin (1936)

- Leonard James Spencer, Meteoric Iron and Silica Glass from the Craters of Henbury (Central Australia) and Wabar (Arabia), Mineralogical Magazine and Journal of the Mineralogical Society, Volume 23, Issue 142, Pages 387-404, Mineralogical Society of Great Britain and Ireland, Oxford University Press, Oxford (1933)

- Bertram Thomas, Arabia Felix: Across the Empty Quarter of Arabia, Jonathan Cape, London (1932)

- Immanuel Velikovsky, Earth in Upheaval, Pocket Books, Simon & Schuster, New York (1955, 1977)

- Susan Whitfield (editor), The Silk Road: Trade, Travel, War and Faith, Serinda Publications Inc, Chicago (2004)

- Charles A Whittaker, The Biblical Significance of Jabal al Lawz, Louisiana Baptist University, Shreveport, Louisiana (2003)

Image Credits

- The Empty Quarter (Arabia): © Al Arabiya (photographers), Fair Use

- Harry St John Bridger Philby: Anonymous Photograph, H St J B Philby, The Heart of Arabia: A Record of Travel and Exploration, Constable and Company, London (1922), Public Domain

- Bertram Sidney Thomas: Walter Westley Russell (artist), Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, University of Cambridge, Public Domain

- Arabia’s Ancient Rivers and Lakes: © H Stewart Edgell, Arabian Deserts: Nature, Origin and Evolution, Springer (2006), Fair Use

- Harrat Rahat: © Jaime S Sincioco (photographer), Fair Use

- Artist’s Impression of Abulfeda: Rebwar Khalid Tahir (artist), Fair Use

- Volcanic Field near Harrat Rahat: © Mohammed Rashad Hassan Moufti & Karoly Nemeth, Geoheritage of Volcanic Harrats in Saudi Arabia (2016), Fair Use

- Jabal Maqla: © Living Passages, Fair Use

- The Black Peak of Jabal Maqla: © The Doubting Thomas Research Foundation (photographers), Fair Use

- Rock from the Peak of Jabal Maqla: © The Doubting Thomas Research Foundation (photographers), Fair Use

- Eugene Shoemaker in the 11 Meter Crater at Wabar: © Jeffrey C Wynn (photograph), The Day the Sands Caught Fire, Fair Use

- The Camel’s Hump (Wabar Meteorite): Thomas J Abercrombie (photographer), © National Geographic, Fair Use

- Map of the Wabar Craters (Philby): Harry St John Bridger Philby (cartographer), Rub’ al Khali: An Account of Exploration in the Great Desert of Arabia, etc, London (1933), © The Estate of St John Philby, Fair Use

- Ruins of Sumhuram in Hadhramaut: Snickeringshadow (photographer), Public Domain

- Ptolemy’s Map of Arabia Felix: © MapPorn (cartographer), Fair Use

- A Reconstruction of Ubar: Madain Project (artists), Encyclopedia of Abrahamic History & Archaeology, After a Drawing by Anne Chalmers in The Road to Ubar (Clapp 202), Fair Use

- Khara-Khota in the Gobi Desert: Anonymous Photograph, Copyright Unknown, Fair Use

- Recently Discovered Remains at Qaryat al-Faw: © Saudi Heritage Commission (photographers), Fair Use

- Map of the Gobi Desert & Environs: Sven Hedin, Riddles of the Gobi Desert, George Routledge & Sons, Ltd, London (1933), Public Domain

- The Ruins of Gaochang: © Zossolino (photographer), Creative Commons License

- Arabia’s Volcanic Regions: © Mohammed Rashad Hassan Moufti & Karoly Nemeth, Geoheritage of Volcanic Harrats in Saudi Arabia (2016), Fair Use