The third part of Chapter VII of Immanuel Velikovsky’s Earth in Upheaval is called The Carolina Bays. The subject of this section are the curious elliptical depressions that dot the Atlantic seaboard of the United States from New York to Florida.

Peculiar elliptical depressions, or “oval craters”, locally called “bays”, are thickly scattered over the Carolina coast of the United States and more sparsely over the entire Atlantic coastal plain from southern New Jersey to northeastern Florida. These marshy depressions are numbered in the tens of thousands and, according to the latest estimate, their number may reach half a million. (Velikovsky 90)

In this section Velikovsky cites four sources, the first three of which believes that meteoritic impacts were responsible for the Carolina Bays:

Douglas Johnson, The Origin of the Carolina Bays (1942)

William Frederick Prouty, Carolina Bays and Their Origin, Bulletin of the Geological Society of America, Volume 63, Pages 167-224 (1952)

Frank Armon Melton & William Schriever, The Carolina “Bays”: Are They Meteorite Scars?, Journal of Geology, Volume 41, Number 1, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago (1933)

Charles Pollard Olivier, Meteors, Williams & Wilkins Company, Baltimore, Maryland (1925)

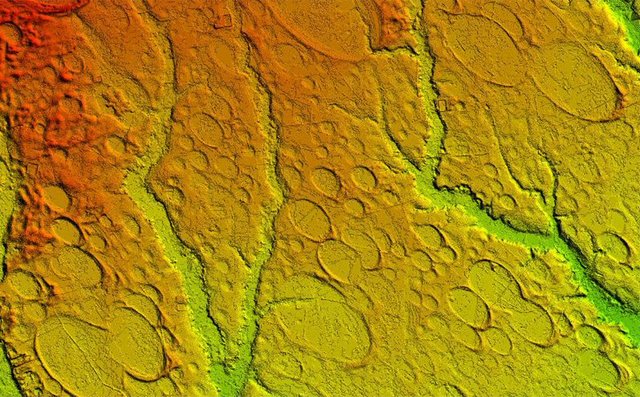

Measurements made on more prominent ones, seaward from Darlington, show that the larger bays average 2200 feet [670 m] in length, and in single cases exceed 8000 feet [2400 m]. A remarkable feature of these depressions is their parallelism: the long axis of each of them extends from northwest to southeast, and the precision of the parallelism is “striking.” Around the bays are rims of earth, invariably elevated at the southeastern end. These oval depressions may be seen especially well in aerial photographs. Any theory as to their origin must explain their form, the ellipticity of which increases with the size of the bays; their parallel alignment; and the elevated rims at their southeastern ends. (Velikovsky 91)

The Meteoritic Hypothesis

In 1933 two professors at the University of Oklahoma, Frank Armon Melton and William Schriever, first proposed a meteoritic origin for the Bays.

Aerial photographs of a district on the coastal plain of South Carolina reveal hitherto unknown relationships among surface depressions of a peculiar type, the origin of which has long been a subject of speculation. These relationships include (1) a smoothly elliptical shape, (2) parallel alinement in a southeastern direction, (3) a peculiar rim of soil which, with unimportant exceptions, is invariably larger at the southeastern end than elsewhere, and (4) mutual interference of outline. Consideration of all of these facts leads to the conclusion that the origin is not directly attributable to ordinary geologic processes. On the contrary, a hypothesis involving impact by a cluster of meteorites is presented as the most reasonable explanation. The supposed swarm must have been large enough to possess a cross-sectional area at right angles to the direction of movement of the order of magnitude of 50,000 square miles [130,000 square kilometres]. (Melton & Schriever 52)

Velikovsky’s direct quote—meteoric shower or colliding comet—is actually a misquote. What the authors wrote is: Meteoritic shower or colliding comet (Melton & Schriever 63). Velikovsky includes four other quotations from this paper:

The authors of the theory stress the fact that, “Since the origin of the bays apparently cannot be explained by the well-known types of geological activity, an extraordinary process must be found. Such a process is suggested by the elliptical shape, the parallel alinement, and the systematic arrangement of elevated rims” [Melton & Schriever 63].

The comet must have struck from the northwest. “If the cosmic masses approached this region from the northwest, the major axes would have the desired alinement” [Melton & Schriever 63]. The time when the catastrophe took place was estimated as sometime during the Ice Age. The bays are “filled to a considerable extent by the deposition of sand and silt, a process which doubtless occurred while the region was covered by the sea during the terrace-forming marine invasion of the Pleistocene [glacial] period” [Melton & Schriever 56]. But the possibility was also envisaged that “the collision [recte collisions] took place” [Melton & Schriever 65] through “the shallow ocean water during the marine invasion” [Melton & Schriever 64]. The swarm of meteorites must have been large enough to hit an area from Florida to New Jersey. (Velikovsky 91)

As Velikovsky notes, the meteoritic theory gained widespread support among mainstream scientists and was the commonly accepted explanation when Earth in Upheaval was written. But alternative explanations of the Bays had already been proposed before Melton & Schriever’s paper appeared, and in 1934 Charles Wythe Cooke of the US Geological Survey published a rebuttal to that paper:

The low elliptical sand ridges in Horry County, South Carolina that were interpreted as meteorite scars by Melton and Schriever are believed to be beach ridges and bars in extinct lakes or lagoons, and to owe their uniform orientation to winds blowing from the ocean. (Cooke & Melton)

Cooke offers three objections to the meteoritic theory:

The ridges around the bays are too small to have been caused by meteoritic impacts, and the rims of the larger bays are no wider than those of much smaller bays.

The arrangement of the bays is not as haphazard as one would expect from a swarm of meteors.

The bays are only found in the lowlying land, which was once covered with water.

Melton’s response to Cooke’s criticisms were published as an addendum to the paper. He believes that the bays Cooke points to in defence of his explanation are not genuine bays:

Figure 5 of Mr. Cooke’s paper illustrates features which are neither closed basins, smoothly elliptical in shape, nor parallel in alinement. They have thus no apparent relationship to the Carolina bays ... The author has examined an entire assemblage of vertical photographs from Barataria Bay, Louisiana, and has found no typical Carolina bays. Figure 5 appears to be from this locality. (Cooke & Melton 97)

On the size of the rims, Melton rejects Cooke’s observation:

It is unquestionably true that the larger bays have the larger rims. They are longer, higher, and in general broader than the rims of the small bays. Many ... are partly covered by vegetation ... This may have led to Mr. Cooke’s error regarding the size of rims. (Cooke & Melton 98)

Melton also rejects—albeit a little tentatively—Cooke’s claim that the arrangement of the bays is to ordered to have been caused by meteoritic impacts:

An aerial mosaic map of a large region must be assembled before positive statements can be made regarding distribution and pattern. As far as the writer has been able to observe, however, the pattern is a random one in respect to surficial processes. (Cooke & Melton 100)

Cooke’s claim that the bays are lowlying features of a former watered land is refuted by a single exception:

Mr. Cooke has observed that one of the elliptical bays exists at an elevation of 270 feet [82 m] above sea level. It is difficult to reconcile this with his statement that “all the elliptical bays appear to lie within lowlands that were once waterways.” (Cooke & Melton 100)

Velikovsky cites Douglas Johnson to the effect that the bays may be of much more recent age than the Pleistocene:

Some critics disagree with the idea that the bays originated in the Ice Age or “are relatively ancient,” and place their origin in a more recent time. The craters were produced by meteoric impact, either by direct hits or by explosion in the air close to the ground, thus causing the formation of vast numbers of depressions. (Velikovsky 91)

It is now generally accepted that the bays were formed before the start of the Holocene, as fossil pollen from many glacial species has been recovered from the sediment in the bays.

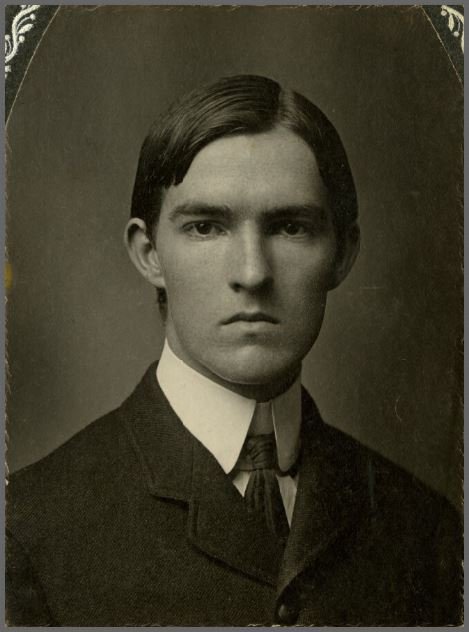

The American astronomer Charles Pollard Olivier was one of the pioneers in the field of meteor science. In 1911 he founded the American Meteor Society, which recruited the services of many amateur astronomers to the field. He wrote two classic texts that ares till read today: Meteors (1925) and Comets (1930). In Meteors, Olivier does not discuss the Carolina Bays. Velikovsky concludes this short section by quoting him on the unusually large number of meteorites that have been recovered in the eastern United States, where the Carolina Bays are found:

But a very large number of meteorites have been discovered in the Southern Appalachian region, in Virginia, North and South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Kentucky and Tennessee. This region has a fairly moist climate, many of the mountains and valleys are densely covered with vegetation, and the population in much of this region is not large. Meteorites here certainly would decay or disintegrate quite rapidly, nevertheless numbers have been found. On the contrary in some of the central states, which are quite level and with denser populations, few if any meteorites have been known to fall. As for the Rocky Mountain region, the population is so small that we hardly can compare it with either of the regions just mentioned. While such a distribution of falls most probably is due to mere chance, yet it is remarkable enough to be worth mentioning (Olivier 240)

The Gradualist Hypothesis

Today Uniformitarians have been at pains to find a gradualist origin for the Carolina Bays. There are still many competing hypotheses, and even the meteoritic hypothesis has some adherents in mainstream academia. Today the most popular hypotheses attempt to explain the bays in terms of various aeolian and lacustrine processes. Christopher S Swezey of the US Geological Survey has recently interpreted the bays as relict thermokarst lakes (Swezey) created during the Last Glacial Maximum (31,100-23,200 BP). These form when permafrost thaws and the landscape is subsequently modified by wind and water. Today such features are found mainly in the Arctic. During the last Ice Age, arctic and subarctic conditions extended much farther south than they do today. But Carolina bays have been found as far south as northern Florida. Pleistocene Florida was cooler and drier than modern Florida, but its climate was not subarctic:

During the Ice Age, one-third of the planet was covered in glaciers, but Florida had temperatures only 5 to 10 degrees cooler than today’s ... (Jill Barton, Los Angeles Times 16 February 2003)

Swezey, however, has contested this view:

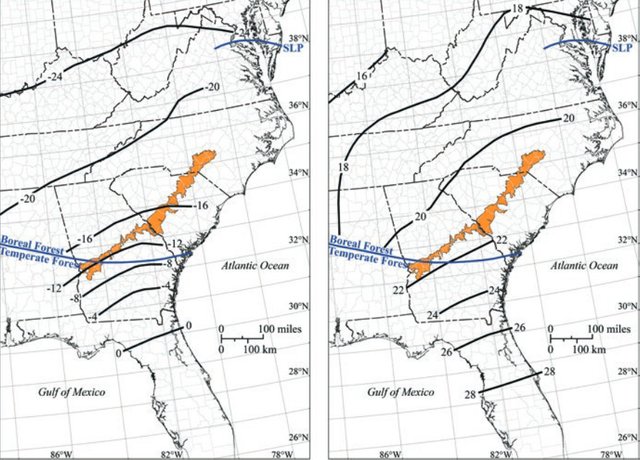

Both the formation of thermokarst lakes and the mobilization of eolian sand in the Atlantic Coastal Plain province would have required cooler air temperatures, greater wind velocities, and reduced vegetation density. The southern limit of continuous permafrost during the LGM [Last glacial Maximum] is generally thought to have been located in central or northern Virginia approximately 230–320 km south of the LGM ice margin ... but the distribution of Carolina Bays suggests that permafrost (possibly discontinuous and/or sporadic) may have extended much farther south. For comparison, during the last glaciation, permafrost in Europe is thought to have extended 800–1200 km south of the LGM ice margin, and permafrost in Asia is thought to have extended 2000–4500 km south of the LGM ice margin ... Furthermore, pollen data from the southeastern United States suggest that the southern limit of boreal forest during the LGM was located in central to southern Georgia (Fig. 2.17). These interpretations are consistent with evidence of LGM iceberg scour on the upper continental slope offshore the coasts of South Carolina, Georgia, and eastern Florida ... In other words, all of these features suggest that the southeastern United States became very cold, dry, and windy during the LGM. (Swezey 55)

The evidence that Florida was relatively warm during the LGM does not support Swezey’s hypothesis, so it must be revised in accordance with his hypothesis. This is not how science is supposed to work.

Recently catastrophist Antonio Zamora has suggested that the bays were formed by secondary impacts:

In the book cited, “The Neglected Carolina Bays”, Antonio Zamora explains that the “Carolina Bays” are the result of the impact of fragments of ice from a glacier cap (the Laurentian Ice Sheet ...) that covered the area of the Great Lakes ... (Botines)

According to Zamora’s hypothesis, these fragments were thrown up when a large meteorite impacted the ice sheet around Saginaw Bay, on Lake Huron. Zamora has a YouTube channel where his theories are explained and demonstrated. His Wikipedia page was recently deleted—a common practice among the narrow-minded gatekeepers of the Wikimedia Foundation.

The meteoritic origins of the Carolina Bays seem obvious to the untrained eye, and I find the various attempts to explain them in terms of gradualist processes strained, and perhaps even a little desperate. But I am not a geologist, so who knows where the truth lies? I think it is fair to say that we have not heard the last word on these curious features.

And that’s a good place to stop.

References

- Charles Wythe Cooke & Frank Armon Melton, Discussion of the Origin of the Supposed Meteorite Scars of South Carolina, Journal of Geology, Volume 42, Number 1, Pages 88-104,The University of Chicago Press, Chicago (1934)

- Douglas Johnson, The Origin of the Carolina Bays, Columbia University Press, New York (1942)

- Frank Armon Melton & William Schriever, The Carolina “Bays”: Are They Meteorite Scars?, Journal of Geology, Volume 41, Number 1, Pages 52-66,The University of Chicago Press, Chicago (1933)

- Charles Pollard Olivier, Meteors, Williams & Wilkins Company, Baltimore, Maryland (1925)

- William Frederick Prouty, Carolina Bays and Their Origin, Geological Society of America Bulletin, Volume 63, Number 2, Pages 167-224, Geological Society of America, Boulder, Colorado (1952)

- Christopher S Swezey, Quaternary Eolian Dunes and Sand Sheets in Inland Locations of the Atlantic Coastal Plain Province, USA, Nicholas Lancaster & Patrick Hesp (editors), Inland Dunes of North America, Pages 11-63, Springer Cham, Cham, Switzerland (2020)

- Immanuel Velikovsky, Earth in Upheaval, Pocket Books, Simon & Schuster, New York (1955, 1977)

- Antonio Zamora, The Neglected Carolina Bays: Ubiquitous Geological Evidence of a Cataclysm, Antonio Zamora (2020)

Image Credits

- The Carolina Bays: Horry County, South Carolina, © MyHorryNews.com, Fair Use

- Carolina Bays (Black & White): Horry County, South Carolina, Fairchild Aerial Surveys, Ocean Forest Company, (1930), Public Domain

- Carolina Bays (LiDAR): LiDAR Digital Elevation Map of the Carolina Bays, Robeson County, North Carolina, United States Geological Survey, Public Domain

- Carolina Bays (Satellite): Bladen County, North Carolina, Fair Use

- Backfilled Carolina Bays: © The Cosmic Tusk, Fair Use

- Charles Olivier Pollard: University of Virginia, Visual History Collection, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, Virginia, Public Domain

- LGM Climate Data of the SE USA, ©Christopher S Swezey, Quaternary Eolian Dunes and Sand Sheets in Inland Locations of the Atlantic Coastal Plain Province, USA, Figure 2.17, Fair Use

- Antonio Zamora: © Sciencebookworm (photographer), Creative Commons License

Video Credits