“Uniformity” is the title Immanuel Velikovsky gave to the third chapter of Earth in Upheaval. In the first of the chapter’s four sections, “The Doctrine of Uniformity,” he briefly traces the origins of this key component of modern geology and evolutionary science, and begins the process of undermining it.

A Psychiatrist’s Perspective

Before he became interested in Catastrophism, ancient history and chronology, Velikovsky’s chosen field of study was psychiatry. In the opening paragraphs of this chapter, he offers a psychiatrist’s perspective on the origins of the Doctrine of Uniformity—also known as Uniformitarianism, or gradualism:

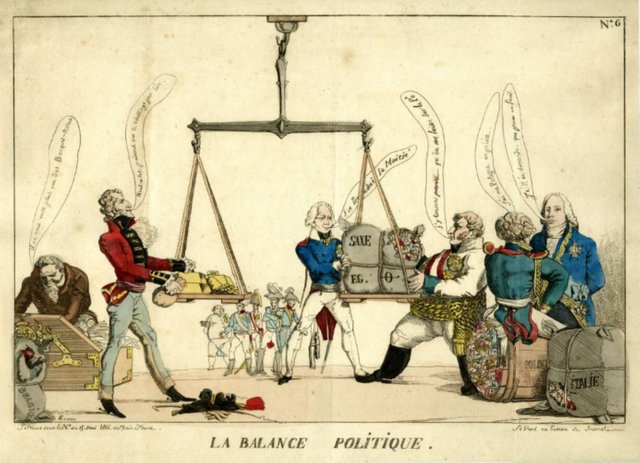

For over twenty-five years, from the beginning of the French Revolution in 1789 to the Battle of Waterloo in 1815; Europe was in turmoil. France beheaded her king and queen; many revolutionaries in their turn went to the scaffold too. Spain, Italy, Germany, Austria, and Russia became battlefields. The British Isles were in danger of being invaded, and Britain’s fleet fought at Trafalgar the tyrant who had sprung up from the revolutionary army. After 1815 there was a universal desire for peace and tranquility. The Holy Alliance was organized; Europe sank into reaction, England into a spirit of conservatism. The abortive revolutionary wave of 1830 did not reach the British Isles.

No wonder that in the climate of reaction to the eruptions of revolution and the Napoleonic Wars the theory of uniformity became popular and soon dominant in the natural sciences. According to this theory, the development of the surface of the globe has been going on through all the ages without any disturbances; the process of very slow change that we observe at present has been the only process of importance from the beginning. (Velikovsky 21)

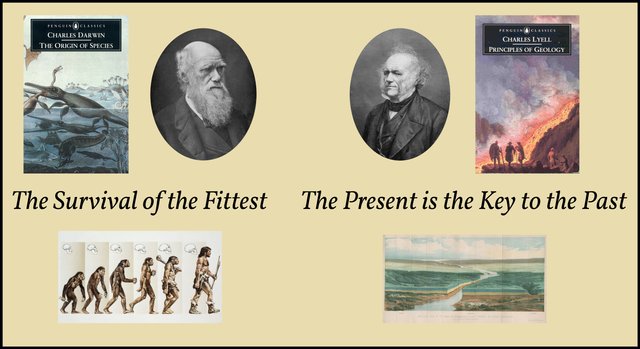

There is probably some truth to this. In the 19th century, British scientists were among the most vocal proponents of Uniformitarianism—notably Charles Lyell and Charles Darwin—while the leading catastrophist of the age was a Frenchman, Georges Cuvier. But several prominent British scholars were also numbered among the ranks of the catastrophists—William Buckland and Henry Hoyle Howorth, for example, both of whom Velikovsky cites in Earth in Upheaval.

The Origin of Uniformitarianism

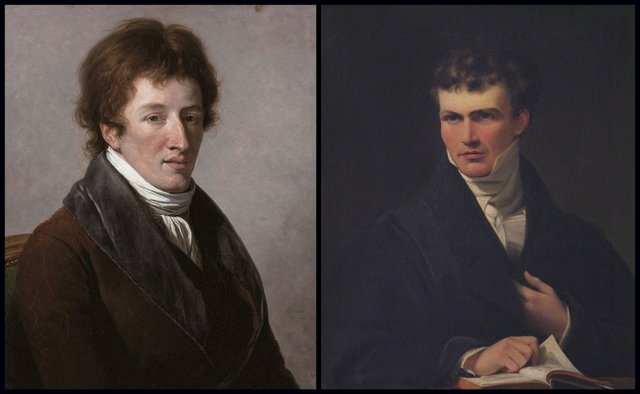

According to Velikovsky, the Doctrine of Uniformity was first advanced at the end of the 18th century by the Scottish geologist James Hutton and the French naturalist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck. It is often said that this doctrine was proposed in opposition to the prevailing theory of Catastrophism, which grew out of a Fundamentalist interpretation of the Bible but was first placed on scientific foundations by Georges Cuvier:

Uniformitarianism is one of the most important unifying concepts in the geosciences. This concept developed in the late 1700s, suggests that catastrophic processes were not responsible for the landforms that existed on the Earth’s surface. This idea was diametrically opposed to the ideas of that time period which were based on a biblical interpretation of the history of the Earth. Instead, the theory of Uniformitarianism suggested that the landscape developed over long periods of time through a variety of slow geologic and geomorphic processes.

The term Uniformitarianism was first used in 1832 by William Whewell, a University of Cambridge scholar, to present an alternative explanation for the origin of the Earth. The prevailing view at that time was that the Earth was created through supernatural means and had been affected by a series of catastrophic events such as the biblical Flood. This theory is called Catastrophism.

The ideas behind Uniformitarianism originated with the work of Scottish geologist James Hutton. In 1785, Hutton presented at the meetings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh that the Earth had a long history and that this history could be interpreted in terms of processes currently observed. For example, he suggested that deep soil profiles were formed by the weathering of bedrock over thousands of years. He also suggested that supernatural theories were not needed to explain the geologic history of the Earth.

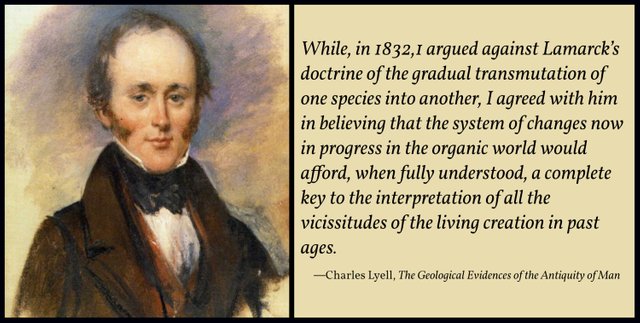

Hutton’s ideas did not gain major support of the scientific community until the work of Sir Charles Lyell. In the three volume publication Principles of Geology (1830-1833), Lyell presented a variety of geologic evidence from England, France, Italy, and Spain to prove Hutton’s ideas correct and to reject the theory of Catastrophism. (Pidwirny & Jones 257-258)

As you can see, the term Uniformitarianism was coined by Whewell in 1832 to describe a theory that was opposed to Catastrophism, which was at that time in the ascendant, but the theory of Uniformitarianism predated Catastrophism—it just failed to gain widespread acceptance until after the rise of Catastrophism.

It is true that Biblical Fundamentalists believed in the Flood, but they did not theorize that mountain ranges were flung up by catastrophes or that the Earth was knocked off its axis by celestial impacts, or that entire populations of animals and plants were routinely annihilated by repeated catastrophes. The Earth, with its mountain ranges and its oceans, and its inhabitants were created less than six thousand years ago by the miraculous intervention of God. Before men like Hutton, the prevailing view was not Catastrophism, but rather an extreme form of Uniformitarianism, one which imagined that the Earth had always looked more or less the way it looks today—since the Flood, at any rate.

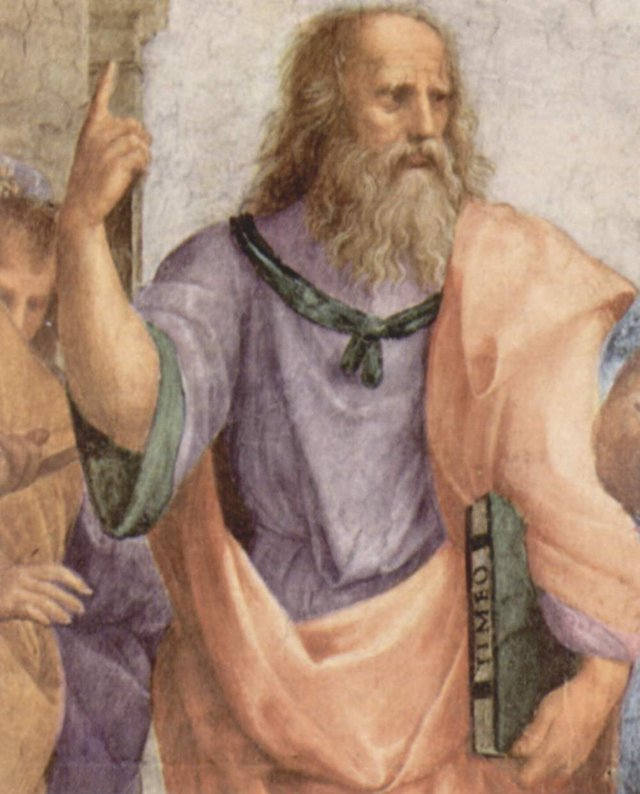

In the ancient world, theories were held to which the names of Uniformitarianism and Catastrophism might be applied. Plato, for example, espoused a catastrophist view of history:

There have been, and there will continue to be, numerous disasters that have destroyed human life in many kinds of ways. The most serious of these involve fire and water, while the lesser ones have numerous other causes. And so also among your people the tale is told that Phaethon, child of the Sun, once harnessed his father’s chariot, but was unable to drive it along his father’s course. He ended up burning everything on the earth’s surface and was destroyed himself when a lightning bolt struck him. This tale is told as a myth, but the truth behind it is that there is a deviation in the heavenly bodies that travel around the earth, which causes huge fires that destroy what is on the earth across vast stretches of time. When this happens all those people who live in mountains or in places that are high and dry are much more likely to perish than the ones who live next to rivers or by the sea. Our Nile, always our savior, is released and at such times, too, saves us from this disaster. On the other hand, whenever the gods send floods of water upon the earth to purge it, the herdsmen and shepherds in the mountains preserve their lives, while those who live in cities, in your region, are swept by the rivers into the sea. But here, in this place, water does not flow from on high onto our fields, either at such a time or any other. On the contrary, its nature is always to rise up from below. This, then, explains the fact that the antiquities preserved here are said to be the most ancient. The truth is that in all places where neither inordinate cold nor heat prevent it, the human race will continue to exist, sometimes in greater, sometimes in lesser numbers. (Timaeus 22 c ff : Cooper 1230)

Strictly speaking, this is a catastrophist account of human history, not geology. In the Timaeus, the material universe is fashioned and shaped by a divine craftsman, or demiurge, who transforms chaos into cosmos. The demiurge does this by using the Platonic Forms—which are perfect, ideal, eternal and unchanging—as models.

Plato’s pupil Aristotle held an opposing view, one that foreshadowed the Doctrine of Uniformity, though he believed that the World had always existed:

Since there is necessarily some change in the whole world, but not in the way of coming into existence or perishing (for the universe is permanent), it must be, as we say, that the same places are not for ever moist through the presence of sea and rivers, nor for ever dry. And the facts prove this ... So it is clear, since there will be no end to time and the world is eternal, that [15] neither the Tanais nor the Nile has always been flowing, but that the region whence they flow was once dry; for their action has an end, but time does not. And this will be equally true of all other rivers. But if rivers come into existence and perish and the same parts of the earth were not always moist, the sea must needs change correspondingly. And if the sea is always advancing in one place and receding in another it is clear that the same parts of the whole earth are not always either sea or land, but that all this changes in the course of time. (Meteorology 352 b 16 ff : Barnes 1258-1259)

These early philosophies of Catastrophism and Uniformitarianism, however, should be distinguished from the modern theories of Hutton and Cuvier, which were developed independently.

The History of Geology

James Hutton is generally regarded as the father of the Doctrine of Uniformity. Before his day, Archbishop Ussher’s date of 4004 BCE for the Creation of the World was still widely accepted as a fundamental fact of history. Ussher’s monumental Annals of the World was first published in 1650 and held sway for about a century. But even before the end of the 17th century the emerging science of geology had begun to undermine Ussher’s Biblical chronology. In fact, some scholars had already begun to chip away at the Fundamentalist position before Ussher was even born:

1544 Georgius Agricola, the Father of Mineralogy, laid the foundations of physical geology, identifying wind and water as the two agents of both orogeny (mountain building) and erosion. His description of how these agents work away continuously over aeons, unnoticed by us short-lived humans, anticipates the mature Doctrine of Uniformity of Charles Lyell (Agricola & Hoover 595 ff, Agricola 33 ff).

1584 In The Expulsion of the Triumphant Beast, the Italian philosopher Giordano Bruno raised doubts concerning the universal nature of the Flood and the Biblical account of the creation of Man. For expressing these opinions he was tried for heresy and burnt at the stake in 1600 (Bruno 249-250).

1669 The Danish clergyman Nicolas Steno laid the foundations of the science of stratigraphy. His Dissertationis prodromus [Preliminary Discourse to a Dissertation], which was intended to be the introduction to a larger work on how fossils and minerals came to be enclosed within solid rocks, hints at the possibility that geological time is of much longer duration than the few millennia the Bible allows. As a Catholic clergyman, however—Steno was a convert from Lutheranism—he accepted Ussher’s Fundamentalist chronology at face value, which forced him to endorse some form of Platonic Catastrophism (Steno 269). In the closing pages of the Prodromus, Steno argued that his views were compatible with Holy Scripture. He never wrote the Dissertation or elaborated on his brief comments on Catastrophism.

1740 The Italian abbot Anton Moro hypothesized that the rocks in the Earth’s crust were formed when molten magma welled up from the mantle and crystallized in the crust as intrusive igneous rock. Some of these igneous rocks were subsequently eroded away, and the resulting fragments were deposited on the ocean floor with organic remains to form sedimentary rocks. This is essentially a uniformitarian doctrine, asserting that petrogenesis is a continuous process that has been taking place throughout the history of the Earth and is still operating today. In the 1790s, this theory would be dubbed Plutonism, to distinguish it from a rival theory known as Neptunism (see below).

1749 Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon estimated that the Earth is 75,000 years old. Buffon is best remembered for his monumental Histoire Naturelle, a 36-volume encyclopaedia on natural history. In Volume 34, Les Époques de la Nature, Buffon surmised that the Earth was about 75,000 years old (Buffon 117-119). Privately, he found even this much too conservative an estimate to account for the accumulation of the Earth’s sediments, thinking 10 million years to be a better estimate. His published views were declared objectionable by the Sorbonne and Buffon was forced to issue a retraction, conceding that his theories were only philosophical speculations. His influence on Lamarck and Cuvier cannot be overstated.

1787 The German geologist Abraham Gottlob Werner argued that rocks in the Earth’s crust were formed when minerals crystallized out of the early oceans. This theory of the aqueous origin of all rocks, known as Neptunism, is similar to the views expressed by Steno, who believed that rocks in the main were created as a result of sedimentation in water (Steno 219). Neptunists, in opposition to the Plutonists, believed that these processes only occurred during the early history of the Earth and are no longer operative. The Plutonists, however, believed that new rocks were still being formed today by volcanic processes, erosion and sedimentation.

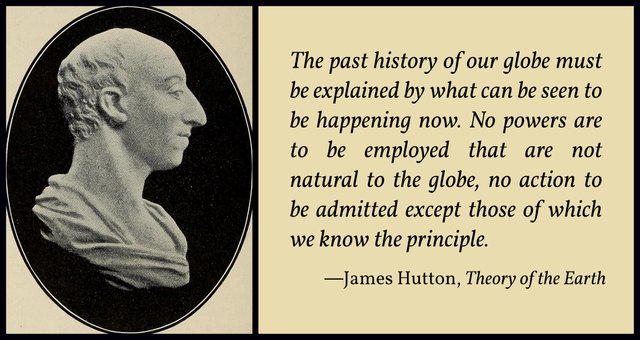

- 1788 Towards the end of the 18th century, the Doctrine of Uniformity came of age with James Hutton’s Theory of the Earth. In this work, Hutton hypothesized that, given enough time, the processes operating today could account for all the features observable in the Earth’s crust today, including rocks, strata, mountains, and valleys. Hutton did not put a precise figure on the age of the Earth, but the closing words of his treatise have an Aristotelian ring to them:

We have now got to the end of our reasoning; we have no data further to conclude immediately from that which actually is; but we have got enough; we have the satisfaction to find, that in nature there is wisdom, system, and consistency. For having, in the natural history of this earth, seen a succession of worlds, we may from this conclude that there is a system in nature; in like manner as, from seeing revolutions of the planets, it is concluded, that there is a system by which they are intended to continue those revolutions. But if the succession of worlds is established in the system of nature, it is in vain to look for any thing higher in the origin of the earth. The result, therefore, of our present enquiry is, that we find no vestige of a beginning—no prospect of an end. (Hutton 304)

In the debate between the Plutonists and the Neptunists, Hutton came down squarely on the side of the Plutonists. In the 19th century, Plutonism gradually gained the upper hand over Neptunism. The plutonic or volcanic nature of the so-called igneous rocks became indisputable. A key battle in the debate concerned the nature of basalt. The Plutonists believed that it was an igneous rock, while the Neptunists asserted that it was sedimentary and contained fossils. When it became clear that basalt did not contain any fossils, the tide turned against Neptunism.

Some critics today assert that the modern theory of rock-formation is actually a sort of Hegelian synthesis of the two opposing viewpoints (van Bemmelen 233). But the essential difference between Plutonism and Neptunism is that the former postulates that rock-formation is an ongoing process, while the latter claims that the conditions for rock-formation no longer obtain. On this point, Plutonism gained a decisive victory over Neptunism.

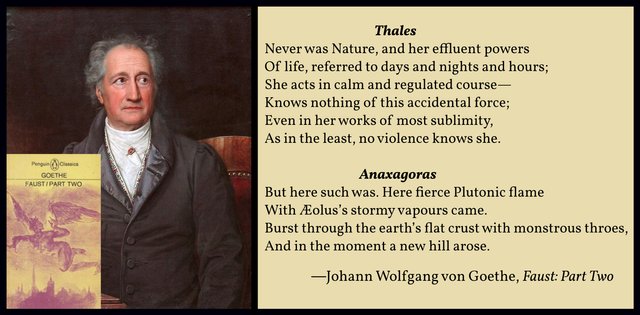

But Neptunism was not a catastrophist theory. In his Faust: Part Two, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe parodies the debate between the Neptunists and the Plutonists when he has two ancient Philosophers, Thales and Anaxagoras, argue over the origins of a rock formation. Thales describes Neptunism as a slow, gradual and gentle process, while Anaxagoras describes Plutonism as violent and sudden. Goethe, who favoured Neptunism, was no catastrophist.

The common misconception of Neptunism as catastrophist and Plutonism as uniformitarian is due to the fact that Hutton, the father of Uniformitarianism, was a Plutonist, while Cuvier, the father of Catastrophism, was a Neptunist.

Biblical Criticism

Parallel to these pioneering efforts in the field of geology, a similar movement arose in the field of Biblical criticism, casting doubt on the infallibility of Holy Scripture, the traditional authorship of the books of the Old Testament, and the belief that the Bible was divinely inspired.

As early as the 12th century, the Jewish scholar Abraham ibn Ezra had anticipated this movement, but he remains an outlier in the field. The modern study of Biblical criticism began in the Renaissance, when a succession of philologists became interested in recovering the original Hebrew text on which the Greek Septuagint and Latin Vulgate translations were based. Initially, these scholars were orthodox Christians, who did not question the divine nature of Holy Scripture—eg Giannozzo Manetti, Lorenzo Valla, Marsilio Ficino, Johannes Reuchlin, Jacques Lefèvre d’Étaples, John Colet, and Desiderius Erasmus. But subsequently, a scholarly debate on the origins of the vowel points in the Hebrew text began to undermine widely-held Christian dogmas:

1538 Elias Levita, Massoreth Ha-Massoreth [Commentary of the Commentary]. This Jewish philologist was the first to hypothesize that the vowel points in the Hebrew Bible were added by rabbinic commentators (the Masoretes) in the city of Tiberias as late as the 5th century of the Common Era. This called into question the dogma that only the traditional authors of the books of the Old Testament had been divinely inspired, not the rabbinic commentators of later centuries.

1624 Louis Cappel, Arcanum Punctuationis Revelatum [The Mystery of Punctuation Revealed]. This Protestant scholar from France was Professor of Hebrew at the Academy of Saumur for the last 45 years of his life, retiring in favour of his son one year before his death. His Arcanum endorsed Levita’s findings. In 1634, however, Cappel broke new ground with his Critica Sacra [Sacred Criticism], which also called into question the authority of the consonants of the Hebrew text of the Old Testament. He accepted that the traditional authors of the various books of the Old Testament had been divinely inspired, but argued that the texts which have been transmitted to us were subject to human error, just like any other written texts. Sacra Critica did not appear in print until 1650—the same year as Ussher’s Annals of the World.

1633 Jean Morin, Exercitationes Biblicae de Hebraeici Graecique Textus Sinceritate [Biblical Exercises on the Soundness of the Hebrew and Greek Text]. A French theologian and a Calvinist who converted to Catholicism, Morin built on Cappel’s work. He argued that the Greek Septuagint translation of the Hebrew Bible is closer to the original, divinely inspired, Hebrew text than the Masoretic text that has come down to us.

1655 Isaac La Peyrère, Prae-Adamitae [The Pre-Adamites]. A French Calvinist who converted to Catholicism and became an Oratorian. He argued that while Adam was the first member of the Jewish race, there were Gentiles who predated his creation. He also cast doubt on the accuracy of extant Biblical manuscripts. His book was widely burned as heretical. He influenced both Baruch Spinoza and his fellow Oratorian Richard Simon.

1670 Baruch Spinoza, Tractatus Theologico-Politicus. This Dutch-born Jewish philosopher is best known for his Ethics, but it is his Tractatus that preserves his Biblical criticism. He approached the Bible with the same critical attitude with which natural philosophers approached nature. This obliged him to hypothesize that the books of the Bible were compiled by many different authors from many different sources. But Spinoza’s work is more exegesis than criticism.

1678 Richard Simon, Histoire Critique du Vieux Testament [Critical History of the Old Testament] French Oratorian, Simon went further than his predecessors by denying the traditional ascription of the Pentateuch to Moses. He was expelled from the Oratorian Order and attempts were made to suppress his book, though a faulty edition came out in Amsterdam in 1680 and an English translation in 1681. He is often described as the “father of higher criticism.”

1740 Johann Christian Edelmann, Moses mit Aufgedecktem Angesicht [Moses with His Face Revealed]. Edelmann continued the work of his predecessors, especially Spinoza and Simon, but did not really break any new ground.

1774-78 Hermann Samuel Reimarus, Apologie oder Schutzschrift für die Vernünftigen Verehrer Gottes [An Apology for, or Some Words in Defense of, the Rational Worshipers of God]. Reimarus is remembered for his Deism, or rational approach to the Christian religion. He was one of the first scholars to treat Jesus Christ as a historical figure, subject to research and study like any other figure in history.

With Reimarus, we have reached the Age of Enlightenment, during which the rational and scientific approach to the Bible became the mainstream. The 19th century was, perhaps, the golden age of Biblical criticism. This was the era of the Tübingen and Göttingen Schools of historical and Biblical research. In this century, scholars could theorize and speculate on the origins of religions and religious texts, including the Bible, without fear of persecution or damage to their professional reputations.

As Velikovsky points out, James Hutton and Jean-Baptiste Lamarck championed the Doctrine of Uniformity at the end of the 18th century—the former in the field of geology, the latter in the field of evolution. But these men were eclipsed in the following century by two successors, Charles Lyell and Charles Darwin. The famous dictum, “the present is the key to the past”, is widely attributed to Lyell. The sentiment is certainly Lyell’s, but I have not been able to find these precise words among his writings.

If the 19th century was the battleground between Catastrophism and Uniformitarianism, then the 20th century was the golden age of the Doctrine of Uniformity. Catastrophists were few and far between, and those who did raise their voices—Velikovsky, for example—were quickly denounced as cranks and crackpots. Velikovsky quotes H F Osborn as a typical representative of the short-sighted and narrow-minded attitude that was widespread in the halls of academia throughout this century:

Present continuity implies the improbability of past Catastrophism and violence of change, either in the lifeless or in the living world; moreover, we seek to interpret the changes and laws of past time through those which we observe at the present time. This was Darwin’s secret, learned from Lyell. (Osborn 24)

Henry Fairfield Osborn was an American geologist and palaeontologist. He was also an advocate of eugenics. He developed his own theory of evolution—the Dawn Man Theory—having been taken in by the Piltdown Man hoax.

Thankfully, the 21st century has seen a resurgence of Catastrophism, with many qualified scientists prepared to champion it and even invoke the heretical name of Velikovsky: Randall Carlson and Ben Davidson are two prominent examples of this new wave.

Principles of Geology

Velikovsky concludes this section with a number of quotations from the 12th edition of Charles Lyell’s opus magnum, the Principles of Geology. The first edition of this historic text appeared in 1830. Lyell continued to revise it for the rest of his life. The 12th and final edition was published in 1875, shortly after the author’s death. The purport of the first few passages Velikovsky quotes may be summarized thus:

The surface of the globe has the appearance of having been subjected to great, violent and sudden changes, but the record is incomplete and the major part of the evidence is lost.

The Doctrine of Uniformity, or of gradual changes in the past measured by the extent of changes observed in the present, has no positive evidence in the incomplete record of the earth’s crust. Consequently, the theory, building on an argumentum ex silentio (argument from silence) requires analogies.

Velikovsky then quotes Lyell’s illustrative analogy:

“Suppose we have discovered two buried cities at the foot of Vesuvius, immediately superimposed upon each other with a great mass of tuff and lava intervening. … An antiquary [archaeologist] might possibly be entitled to infer, from the inscriptions on public edifices, that the inhabitants of the inferior and older city were Greeks, and those of the modern town Italians. But he would reason very hastily if he also concluded from these data, that there had been a sudden change from the Greek to the Italian language in Campania. But if he afterwards found three buried cities, one above the other, the intermediate one, being Roman ... he would then perceive the fallacy of his former opinion, and would begin to suspect that the catastrophes, by which the cities were inhumed, might have no relation whatever to the fluctuations in the language of the inhabitants; and that, as the Roman tongue had evidently intervened between the Greek and Italian, so many other dialects may have been spoken in succession, and the passage from the Greek to the Italian may have been very gradual. (Lyell 316)

Velikovsky finds it curious that Lyell chooses as his analogy for Uniformitarianism an example from history in which a violent and sudden catastrophe played a crucial rôle:

This often-reprinted passage is an unfortunate example, for, in order to prove that there had been no violent changes, Lyell chose to present a picture of violent catastrophes: the strata are separated by layers of lava. This is also the picture presented in so many geological surveys. To use this example as a proof of uniformity is a flight of dialectics. (Velikovsky 24)

The next few quotations from Lyell make the following arguments:

Earlier geologists had only a scanty acquaintance with existing changes and were singularly unconscious of the extent of their ignorance. They decided that time could never enable the existing powers of nature to work out changes of great magnitude, still less such important revolutions as those which are brought to light by geology.

This assumption of the discordance between ancient and current causes of change fostered indolence and blunted the edge of curiosity. It produced a state of mind unable to accept the evidence that minute but incessant alterations are taking place in every part of the earth’s surface.

For this reason all theories are rejected which involve the assumption of sudden and violent catastrophes and revolutions of the whole earth, and its inhabitants—theories which are restrained by no reference to existing analogies, and in which a desire is manifested to cut, rather than patiently to untie, the Gordian knot.

Velikovsky is not impressed by this logic:

Notwithstanding the strong language employed, the scientific principle which insists that whatever does not occur at the present time has not occurred in the past is a self-imposed limitation. Rather than a principle in science, it is a statute of faith. (Velikovsky 25)

Velikovsky gives Lyell the last word in this section:

And Lyell ended his famous chapter accordingly, with an appeal for faith and with a precept for believers:

“If he [the student] finally believes in the resemblance or identity of the ancient and present systems of terrestrial changes, he will regard every fact collected respecting the causes in diurnal action as affording him a key to the interpretation of some mystery in the past.” (Lyell 319, Velikovsky 25)

And that’s a good place to stop.

References

- Georgius Agricola, De Ortu et Causis Subterraneorum [On Subterranean Origins and Causes], Hieronymus Froben & Nicolaus Episcopius, Basel (1544)

- Georgius Agricola, Herbert Clark Hoover (translator), Lou Henry Hoover (translator), De Re Metallica, The Mining Magazine, London (1912)

- Jonathan Barnes (editor), The Complete Works of Aristotle, Volumes 1 & 2, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ (1984)

- Giordano Bruno, Arthur D Imerti (translator), The Expulsion of the Triumphant Beast, Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, NJ (1964)

- Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, Les Époques de la Nature, L’Imprimerie Royale, Paris (1780)

- John M Cooper, Plato: Complete Works, Hackett Publishing Company, Indianapolis (1997)

- James Hutton, Theory of the Earth, Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, Volume 1, Part 2, Pages 209-304, Royal Society of Edinburgh, Edinburgh (1788)

- Charles Lyell, Principles of Geology, 12th Edition, Volume 1, Volume 2, John Murray, London (1875)

- Michael J Pidwirny, Fundamentals of Physical Geology, Version 1.3, Online Publication (2002)

- Anton-Lazzaro Moro, De’ Crostacei e Degli Altri Marini Corpi Che Si Trouvano su Monti [On Crustaceans and Other Marine Creatures Found on Mountaintops], Stephano Monti, Venice (1740)

- Henning Graf Reventlow, History of Biblical Interpretation, Volumes 1-4, Society of Biblical Literature, Atlanta, GA (2009-2010)

- Nicolas Steno, John Garrett Winter (translator), The Prodromus of Nicolaus Steno’s Dissertation Concerning a Solid Body Enclosed by Process of Nature within a Solid: An English Version with an Introduction and Explanatory Notes, The Macmillan Company, New York (1916)

- Reinout Willem van Bemmelen, The Geology of Indonesia, Volume 1A: General Geology of Indonesia and Adjacent Archipelagoes, Government Printing Office, The Hague (1949)

- Immanuel Velikovsky, Earth in Upheaval, Pocket Books, Simon & Schuster, New York (1955, 1977)

Image Credits

- Charles Darwin: Daniel Coit Gilman et al (editors), The New International Encyclopædia, Volume 5, Facing Page 798, Dodd, Mead and Company, New York (1905), Public Domain

- Charles Lyell: Illustrated London News, 27 February 1875, Volume 66, Number 1855, Facing Page 204, Public Domain

- The Origin of Species: © Penguin Classics, Henry De la Beche, Duria Antiquior, Frontispiece, Fair Use

- Principles of Geology: © Penguin Classics, Jakob Philipp Hackert, The Vesuvius Eruption in 1774, Museumslandschaft Hessen Kassel, Fair Use

- The Descent of Man: De Agostini Picture Library, Getty Images, Fair Use

- Niagara Falls and Environs: Charles Lyell, Travels in North America, Frontispiece, John Murray, London (1845), Public Domain

- The Political Balance: La Balance Politique, Eugène Delacroix (attributed), Caricature to Accompany Le Nain Jaune, 15 May 1815, Pages 191-192, © The Trustees of the British Museum, Creative Commons License

- James Hutton: Henry Raeburn (artist), Scottish National Gallery, Public Domain

- Jean-Baptiste Lamarck: Charles Thévenin (artist), Private Collection, Public Domain

- Georges Cuvier: François-André Vincent (artist), Private Collection, Public Domain

- William Whewell: James Lonsdale (artist), Trinity College, Cambridge, Public Domain

- Raphael’s Plato with the Timaeus: The School of Athens (detail), Raphael (artist), Stanza della Segnatura, Vatican City, Public Domain

- Rembrandt’s Aristotle Contemplating a Bust of Homer: Rembrandt van Rijn, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Public Domain

- Georgius Agricola: Anonymous, Public Domain

- Giordano Bruno: Anonymous, Public Domain

- Nicolas Steno: Anonymous, Public Domain

- Anton Moro: Benedetto Musitelli (engraver), Adalberto Sartori Collection, Mantua, Public Domain

- Le Comte de Buffon: François-Hubert Drouais (artist), Musée Buffon, Montbard, Public Domain

- Abraham Gottlob Werner: Ludwig Theodor Zöllner (lithographer), Public Domain

- James Hutton: George McCready Price, God’s Two Books, or, Plain Facts about Evolution, Geology, and the Bible, Page 92, Review and Herald Publishing Association, Washington, DC (1911), Public Domain

- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe: Karl Joseph Stieler (artist), Neue Pinakothek, Munich, Public Domain

- Faust: Part Two: © Penguin Classics (design), Mephistopheles over Wittenberg, Eugène Delacroix (lithographer), Public Domain

- Abraham ibn Ezra: 13th Century Miniature, Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, Paris, Public Domain

- Massoreth Ha-Massoreth: © Forgotten Books, Fair Use

- Louis Cappel: Anonymous Engraving, National Portrait Gallery, London, Public Domain

- Jean Morin: Jacques Lubin (engraver), Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris, Public Domain

- Baruch Spinoza: Herzog August Library, Wolfenbüttel, Germany, Public Domain

- Histoire Critique du Vieux Testament: © Kessinger Publishing (design), Fair Use

- Prae-Adamitae: © Kessinger Publishing, Fair Use

- Johann Christian Edelmann: Georg Friedrich Schmoll (engraver), Public Domain

- Hermann Samuel Reimarus: Gerloff Hiddinga (artist), Public Domain

- Charles Lyell: Alexander Craig (artist), Public Domain

- Randall Carlson: © Randall Carlson, Fair Use

- Ben Davidson: © Ben Davidson, Fair Use

- The Last Day of Pompeii: Karl Bryullov (artist), Russian Museum, Saint Petersburg, Public Domain

- Alexander Cuts the Gordian Knot: Jean-Simon Berthélemy (artist), Beaux-Arts de Paris, Paris, Public Domain