“The Hippopotamus” is the second section of Chapter III of Immanuel Velikovsky’s Earth in Upheaval. In this short section, Velikovsky wonders whether Uniformitarianism can account for the presence of hippopotamus bones in parts of the World where the hippopotamus is not currently extant. Were these bones buried in situ at a time when the hippopotamus flourished in these regions, or were they carried there by catastrophic floods from distant parts of the globe?

Charles Lyell, who discussed the matter in his Geological Evidences of the Antiquity of Man, perceived that there was puzzle here that needed solving:

The ossiferous caves of the peninsula of Gower in Glamorganshire have been diligently explored of late years by Dr. Falconer and Lieutenant-Colonel E. R. Wood, the latter of whom has discovered and thoroughly investigated the contents of many which were previously unknown. Among their contents have been found the remains of almost every quadruped elsewhere found fossil in British caves: in some places the Elephas primigenius, accompanied by its usual companion the Rhinoceros tichorhinus, in others Elephas antiquus associated with Rhinoceros hemitœchus Falconer; the extinct animals being often embedded, as in the Belgian caves, in the same matrix with species now living in Europe, such as the common badger (Meles taxus) the common wolf, and the fox.

In a cavernous fissure called the Raven’s cliff, teeth of several individuals of Hippopotamus major, both young and old, were found; and this in a district where there is now scarce a rill of running water, much less a river in which such quadrupeds could swim. In one of the caves, called Spritsail Tor, both of the elephants above named were observed, with a great many other quadrupeds of recent and extinct species. (Lyell 172)

The coexistence of tropical and temperate species in Wales makes no sense. If the climate was favourable to elephants, rhinoceroses and hippopotami, it would not have been favourable to badgers, wolves or foxes—and vice versa. Lyell offered the following solution to this enigma:

As I have alluded more than once in this chapter ... to the occurrence of the remains of the hippopotamus in places where there are now no rivers, not even a rill of water ... it may be well to consider, before proceeding farther, what geographical and climatal conditions are indicated by the presence of these fossil pachyderms.

It is now very generally conceded that the mammoth and tichorhine rhinoceros were fitted to inhabit northern regions, and it is therefore natural to begin by asking whether the extinct hippopotamus may not in like manner have flourished in a cold climate. In answer to this enquiry, it has been remarked, that the living hippopotami, anatomically speaking so closely allied to the extinct species, are so aquatic and fluviatile in their habits, as to make it difficult to conceive that their congeners could have thriven all the year round in regions where, during winter, the rivers were frozen over for months. Moreover, I have been unable to learn that, in any instance, bones of the hippopotamus have been found in the drift of northern Germany associated with the remains of the mammoth, tichorhine rhinoceros, musk-buffalo, reindeer, lemming, and other arctic quadrupeds before alluded to (p. 157); yet, though not proved to have ever made a part of such a fauna, the presence of the fossil hippopotamus north of the fiftieth parallel of latitude naturally tempts us to speculate on the migratory powers and instincts of some of the extinct species of the genus. They may have resembled, in this respect, the living musk-buffalo, herds of which pass for hundreds of miles over the ice to the rich pastures of Melville Island, and then return again to southern latitudes before the ice breaks up ...

The geologist, therefore, may freely speculate on the time when herds of hippopotami issued from North African rivers, such as the Nile, and swam northwards in summer along the coasts of the Mediterranean, or even occasionally visited islands near the shore. Here and there they may have landed to graze or browse, tarrying awhile and afterwards continuing their course northwards. Others may have swum in a few summer days from rivers in the south of Spain or France to the Somme, Thames, or Severn, making timely retreat to the south before the snow and ice set in. (Lyell 178-181)

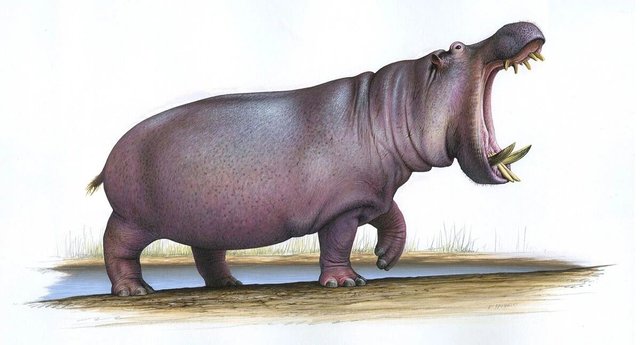

Lyell’s fanciful theory of migratory hippos has not fared well. Today, palaeontologists believe that the extinct species Hippopotamus antiquus—known to Lyell as Hippopotamus major—ranged throughout Europe during the Early and Middle Pleistocene (2.6-0.1 Ma). This simply ignores Lyell’s objection—the unlikelihood that this species could have survived harsh European winters. It also fails to address the question of how tropical and temperate species could have flourished side by side in the same environment.

Yorkshire and North Wales

In addition to the bone caves on the Gower Peninsula in the south of Wales, Velikovsky draws attention to two other ossiferous caverns: Victoria Cave near Settle in western of Yorkshire, and Cae Gwyn in the Vale of Clwyd in northern Wales. Velikovsky’s source for these is the second edition of H B Woodward’s The Geology of England and Wales.

Horace Bolingbroke Woodward (1848-1914) was the son and grandson of distinguished geologists. He participated in the Geological Survey of England and Wales from 1867 until his retirement in 1908. He became a Fellow of the Geological Society in 1868, and was its vice-president between 1904 and 1906. He was a recipient of both the Murchison Medal (1897) and the Wollaston Medal (1909), two of the Society’s most prestigious awards in the field of geology.

The inner chamber of Victoria Cave was allegedly discovered on 20 June 1837, the day Queen Victoria acceded to the British throne—hence the name. Woodward, however, gives 1838 as the year of discovery (Woodward 542). It is the most notable of several ossiferous fissure in the district. Velikovsky’s brief account of the cave does not accord precisely with the details given in Woodward’s Geology of England and Wales, which may indicate that Velikovsky was also drawing upon another uncited source:

The Settle Cave (1450 feet [442 m] above the level of the sea) was discovered in 1838, and has since been explored chiefly by Mr. R. H. Tiddeman. [Footnote: Brit. Assoc. 1874, 1875 ; The Work and Problems of the Victoria Cave, 1875 ; G. Mag. 1873, p. II ; see also J. R. Dakyns, G. Mag. 1877, p. 439.] The upper bed in it was formed of stones which had fallen from the roof; then beneath came a black bed, containing charcoal, and highly artistic enamelled ornaments, showing a date of occupation that was post-Roman. To these succeeded layers six feet in thickness, in which were found remains of a more ancient race, their flint knives, harpoons, etc. Beneath these deposits, classed as Neolithic and Roman, the following beds were determined:—

Upper Cave-earth, with Badger, Reindeer, Horse, etc.

Laminated Clay, with a few small well-glaciated boulders.

Lower Cave- earth, with Hyaena, Bear, Elephas antiquus, Rhinoceros, Hippopotamus, Bos primigenius, and a human fibula?

Some doubt has been thrown on the identification of this human bone; but Mr. Busk, while disposed to regard it as an abnormally large human fibula, thought it would be unsafe to build any strong conclusions upon it.

The clay found in the cave was regarded by Mr. Tiddeman as of Glacial age. (Woodward 542)

Compare this with Velikovsky’s summary:

In the Victorian cave near Settle, in west Yorkshire, 1450 feet above sea level, under twelve feet of clay deposit, containing some well-scratched boulders, were found numerous remains of the mammoth, rhinoceros, hippopotamus, bison, hyena, and other animals. (Velikovsky 26)

Nor do the Tiddeman sources cited by Woodward fit. An online search, however, has led me to conclude that Velikovsky supplemented Woodward’s account with one found in Henry Williamson Haynes & George Frederick Wright’s Man and the Glacial Period:

The Victoria cave, near Settle, in west Yorkshire, is the only other one in England which we need to mention. In this there were no remains found which could be positively identified as human, but the animal remains in the lower strata of the cave deposit were so different from those in the upper bed as to indicate the great lapse of time which separated the two. This cave is 1,450 feet above the sea-level, and there were found in the upper strata of the floor, down to a depth of from two to ten feet, many remains of existing animals. Then, for a distance of twelve feet, there occurred a clay deposit, containing no organic remains whatever, but some well-scratched boulders. Below this was a third stratum of earth mingled with limestone fragments, at the base of which were numerous remains of the mammoth, rhinoceros, hippopotamus, bison, hyena, etc. One bone occurred which was by some supposed to be human, but by others to have belonged to a bear. This lower stratum is, without much doubt, preglacial, and the thickness of the deposit intervening between it and the upper fossiliferous bed is taken by some to indicate the great lapse of time separating the period of the mammoth and rhinoceros in England from the modern age. The scratched boulders in the middle stratum of laminated clay, would indicate certainly that the material found its way into the cave during the Glacial epoch, when ice filled the whole valley of the Kibble, which flows past the foot of the hill, and whose bed is 900 feet below the mouth of the cave. (Haynes & Wright 270-271)

I am guessing that Velikovsky misread “The Victoria cave” as “The Victorian cave”, but otherwise the details in his account match those of Haynes & Wright’s.

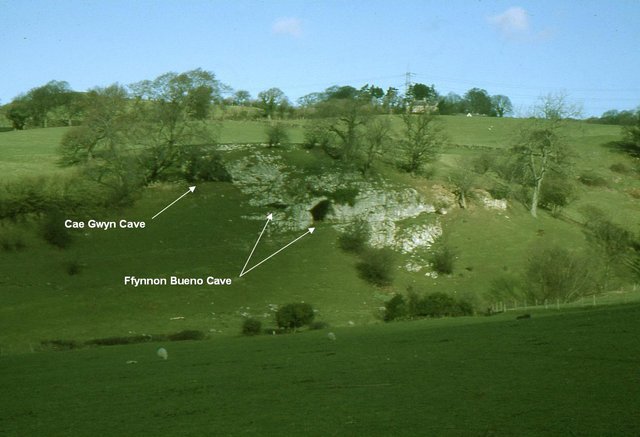

The other ossiferous fissure that Velikovsky references in this section, Cae Gwyn Cave in the Vale of Clwyd in northern Wales, is also described by Haynes & Wright, but Velikovsky only cites Woodward, whom he explicitly quotes:

In northern Wales in the Vale of Clwyd, in numerous caves remains of the hippopotamus lay together with those of the mammoth, the rhinoceros, and the cave lion. In the cave of Cae Gwyn in the Vale of Clwyd, “during the excavations it became clear that the bones had been greatly disturbed by water action. The floor of the cavern was “covered afterwards by clays and sand containing foreign pebbles. This seemed to prove that the caverns, now 400 feet [above sea level], must have been submerged subsequently to their occupation by the animals and by man. ... The contents of the cavern must have been dispersed by marine action during the great submergence in mid-glacial times, and afterwards covered by marine sands ...” writes H. B. Woodward. (Velikovsky 26)

Once again, however, there are some details in Velikovsky’s account that are not in Woodward’s:

The most important evidence, however, is that the Bone-earth at Cae Gwyn is overlaid by Boulder Clay. The Beds were as follows:—Below the soil, for about 8 feet, a tolerably stiff Boulder Clay, containing many ice-scratched boulders and narrow bands and pockets of sand. Below this about seven feet of gravel and sand, with here and there bands of red clay, having also many ice-scratched boulders. The next deposit was a laminated brown clay, and under this was found the bone-earth, a brown, sandy clay with small pebbles and with angular fragments of limestone, stalagmite, and stalactites. During the excavations it became clear that the bones had been greatly disturbed by water action, that the stalagmite floor, in parts more than a foot in thickness, and massive stalactites had also been broken and thrown about in all positions, and that these had been covered afterwards by clays and sand containing foreign pebbles. This seemed to prove that the caverns, now 400 feet above Ordnance datum, must have been submerged subsequently to their occupation by the animals and by man. In Dr. Hicks’ opinion the contents of the cavern must have been disturbed by marine action during the great submergence in mid-Glacial times, and afterwards covered by marine sands and by an upper Boulder Clay, identical in character with that found at many points in the Vale of Clwyd. The palæontological evidence suggests that the deposits in question are not Pre-Glacial, but may be equivalent to the later Pleistocene deposits of our river-valleys.(Woodward 543-544)

The missing details in Velikovsky’s account can be found in Haynes & Wright’s account of Cae Gwyn:

In North Wales the Vale of Clwyd contains numerous caves which were occupied by hyenas in preglacial times and with their bones are associated those of the mammoth, the rhinoceros, the hippopotamus, the cave lion, the cave bear, and various other animals. Flint implements also were found in the cave at Cae Gwyn, near the village of Tremeirchon, on the eastern side of the valley, opposite Cefn, and about four miles distant. (Haynes & Wright 271)

A Catastrophist Solution

Velikovsky is not impressed by Woodward’s explanation of how the bones ended up in these caves beneath gravel and sand, with clear signs of having been disturbed by marine action:

Three assumptions were made by the exponents of uniformity: Sometime not long ago the climate of the British Isles was so warm that hippopotami used to visit there in summer; the British Isles subsided so much that caves in the hills became submerged; the land rose again to its present height—and all this without any action of a violent nature. (Velikovsky 27)

He suggests that Catastrophism provides a simple solution to all the problems raised by these ossiferous fissures:

Or was it, perchance, a mountain-high wave that crossed the land and poured into the caves and filled them with marine sand and gravel? Or did the ground submerge and then emerge again in some paroxysm of nature in which the climate also changed? Did the animals run away at the sign of the approaching catastrophe, and did the trespassing sea follow and suffocate them in the caves that were their last refuge and became the place of their burial? Or did the sea sweep them from Africa, throw them in heaps on the British Isles and in other places, and cover them with earth and marine debris? The entrances to some caves were too narrow and the caves themselves too “shrunk” (contracted) to have been places of refuge for such huge animals as hippopotami and rhinoceroses. Whichever of these answers or surmises is correct, and whether the hippopotami lived in England or were thrown there by the ocean, whether they sought refuge in caves or the caves are but their graves, their bones on the British Isles, as also on the bottom of the seas surrounding these islands, are signs of some great natural change. (Velikovsky 27)

And that’s a good place to stop.

References

- Henry Williamson Haynes & George Frederick Wright, Man and the Glacial Period, Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co Ltd, London (1892)

- Charles Lyell, The Geological Evidences of the Antiquity of Man, John Murray, London (1863)

- Immanuel Velikovsky, Earth in Upheaval, Pocket Books, Simon & Schuster, New York (1955, 1977)

- Horace Bolingbroke Woodward, The Geology of England and Wales, Second Edition, George Philip & Son, London (1887)

Image Credits

- European Hippopotamus (Hippopotamus antiquus): © Robert Nicholls (artist), Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences, Fair Use

- Raven’s Cliff Cave: © Steve Dagnall (photographer), Gower Bone Caves, Fair Use

- Spritsail Tor (Prissen’s Tor): © Gower Bone Caves, Fair Use

- Victoria Cave (North Yorkshire): ©JPIMedia Publishing Ltd, Fair Use

- Victoria Cave (Main Chamber): © Stephen C Oldfield (photographer), Fair Use

- Cae Gwyn Cave (Vale of Clwyd): © Llywelyn2000 (photographer), Creative Commons License

- Cae Gwyn and Ffynnon Bueno Caves: © Cambrian Caving Council, Fair Use

- Wilfried Rosendahl of the Reiss Engelhorn Museum: Rebecca Kind (photographer), Wilfried Rosendahl, Generaldirektor der Reiss-Engelhorn-Museen, Mannheim, © REM, Fair Use