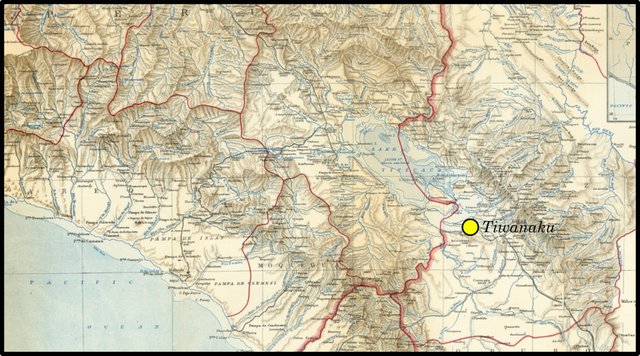

The fourth section of Chapter VI of Immanuel Velikovsky’s Earth in Upheaval is concerned with the mysterious South-American city of Tiwanaku, which is situated on the shores of Lake Titicaca, in the Bolivian highlands. The existence of a major city at such an altitude and in such a desolate landscape seems at odds with the conventional chronology of the site. According to current thinking, the site was probably founded no earlier than the 1st century CE, reached its height around 700, and collapsed around 1000. Contrast this with the views expressed by earlier scholars, such as the Austrian scientist Arthur Posnansky, who dated the construction of the city to 15,000 BCE.

In the Andes, at 16° 22' south latitude, a megalithic city was found at an elevation of 12,500 feet [3800 m], in a region where corn will not ripen. The term “megalithic” fits the dead city only in regard to the great size of the stones in its walls, some of which are flattened and joined with precision. It is situated on the Altiplano, the elevated plain between the Western and Eastern Cordilleras, not far from Lake Titicaca, the largest lake in South America and the highest navigable lake in the world, on the border of Bolivia and Peru.

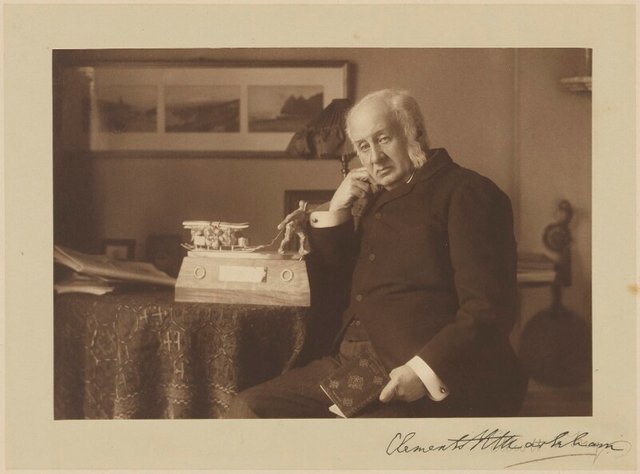

“There is a mystery still unsolved on the plateau of Lake Titicaca, which, if stones could speak, would reveal a story of deepest interest. Much of the difficulty in the solution of this mystery is caused by the nature of the region, in the present day, where the enigma still defies explanation.” So wrote Sir Clemens Markham in 1910. “Such a region is only capable of sustaining a scanty population of hardy mountaineers and laborers. The mystery consists in the existence of ruins of a great city at the southern side of the lake, the builders being entirely unknown. The city covered a large area, built by highly skilled masons, and with the use of enormous stones.” (Velikovsky 75)

Velikovsky misspells the forename of his first source, Clements Markham, an English geographer and explorer of the 19th century. As President of the Royal Geographical Society, Markham organized the British National Antarctic Expedition of 1901-1904, which launched the Polar careers of Robert Scott, Ernest Shackleton, and several other celebrated explorers. An indefatigable explorer in his own right and a prolific author, Markham’s travels took him as far afield as India, South America, Abyssinia and the Polar regions. In 1850 he took part in the search for the missing Franklin Expedition in the Arctic Ocean. In 1875 he returned to the Arctic as a guest of the British National Antarctic Expedition. He left the expedition after three months, when it had reached Disko Island, on the west coast of Greenland. A few months later, his cousin Albert Hastings Markham led the sledging party that set a new record for the Farthest North.

Clements Markham was also a prolific writer and diarist. In addition to the many papers and reports he prepared for the Royal Geographical Society and other learned bodies, he penned dozens of histories, biographies and travelogues. He also translated numerous works from Spanish and compiled a grammar and dictionary for Quechua, the language of the Peruvian Incas. Of these works Velikovsky cites only one, The Incas of Peru, which was first published in London in 1910, when Markham had just turned 80.

On page 37, Markham poses the riddle:

But we must return to the most difficult part of the problem, namely, the climatic conditions. How could such a region as is described at the beginning of this essay, where corn cannot ripen, sustain the population of a great city over 12,000 ft. above the level of the sea? Could the elevation have been less? Is such an idea beyond the bounds of possibility? The height is now 12,500 ft. above the sea level, in latitude 16° 22' S ...

But at a remote geological period there was no South America, only three land masses, separated by great sea inlets, a Guiana, a Brazil, and a La Plata island. There were no Andes. Then came the time when the mountains began to be upheaved. The process appears to have been very slow, gradual, and long continued. The Andes did not exist at all in the Jurassic, or even in the cretaceous period. Comparatively speaking, the Andes are very modern ... When the Andes were lower, the trade wind could carry its moisture over them to the strip of coast land which is now an arid desert, producing arboreal vegetation and the means of supporting gigantic ant-eaters. When mastodons lived at Ulloma, and ant-eaters in Tarapaca, the Andes, slowly rising, were some two or three thousands of feet [600-900 m] lower than they are now. Maize would then ripen in the basin of Lake Titicaca, and the site of the ruins of Tiahuanacu could support the necessary population. If the megalithic builders were living under these conditions, the problem is solved. If this is geologically impossible, the mystery remains unexplained. (Markham 37-38)

Velikovsky recounts an interesting story concerning this possibility:

When the author of the quoted passages posed his question to the scholarly world, Leonard Darwin, then president of the Royal Geographical Society, offered the surmise that the mountain had risen considerably after the city had been built. (Velikovsky 75)

No citation is given for this nugget of information, which was not taken from The Incas of Peru. On 9 May 1910, shortly before the publication of The Incas of Peru, Markham presented a paper on the same subject to the Royal Geographical Society, followed by a discussion among several members. It was during this discussion that the President Leonard Darwin made his remarks, which were included as an appendix to the lecture in Volume 36 of The Geographical Journal:

The PRESIDENT (after the paper): The extremely interesting paper which we have just heard read will, of course, appear in the ordinary course in the Journal. To it will be added a note, drawn up by Mr. Reeves, our Map Curator, giving further information with regard to the compilation and the authorities for the map; and this note will, I am sure, confirm what Sir Clements has said about the extreme difficulty of compiling this map, and as to its being likely to be the best map of Peru for many years to come. As to Sir Clements’ paper, it can hardly fail to give rise to an interesting discussion, as there are so many interesting points in it. One suggestion which he has made is naturally of special interest to me, namely, the suggestion—I may say the almost startling suggestion—that the Andes have risen 1000 feet in height since certain stone remains were deposited there by man, thus causing a material alteration in the climate. It is especially interesting to me, because of the mention of my father’s name in connection with it. In these circumstances I naturally turned to the ‛Voyage of the Beagle,’ and there I found most ample evidence of the very strong impression that had been made on my father’s mind by the evidences on the west coast of South America of great changes in the level of the land. In fact, in the short quotation I propose to read to you, I feel at a loss to know to what extent it should be regarded as sound geology and to what extent as poetic licence. “Daily it is forced home on the mind of the geologist, that nothing, not even the wind that blows, is so unstable as the level of the crust of the Earth.” If that were the literal truth, there would indeed be no difficulty in connection with Sir Clements Markham’s suggestion as to the rise in the Andes.

In considering this question, what we should like to know in the first place is, what is the age of these ancient ruins? On that point there is no evidence whatever, but judging by the age now generally assigned to the pyramids of Egypt, it would not be an outrageous supposition to suggest that these megalithic remains may be 4000 years old. Then as to the changes of level. Referring again to the ‛Voyage of the Beagle,’ one instance is there given of a rise of 11 feet in seventeen years. That, of course, is a much greater rise than is necessary to tally with Sir Clements Markham’s suggestion, and perhaps it is unfair to quote it, as it no doubt took place in a period of exceptional movement. Another case is given where the rise appears to have been close on 19 feet during 220 years. Let us say, then, it does not appear to be out of the question to suppose that land in South America may have risen 20 feet in 200 years, or 400 feet in 4000 years. But this rise was near the coast-line, and there is ample geological evidence to prove that the rise in recent geological times has been much greater inland than at the coast. If the rise at Lake Titicaca were two and a half times the rise at the coast, and the rise at the coast could have amounted to 400 feet in the assumed time, than we have a possible rise at Lake Titicaca of 1000 feet. Thus it seems to me that the facts we know do not, at all events, run counter to Sir Clements Markham’s suggestion. It occurred to me, in considering this question, that if this rise of 1000 feet really took place, it must have shown itself in a tilting of the buildings. This is, however, not the case. If the land near Lake Titicaca rose 1000 feet, whilst the land near the coast remained quite stationary, this would necessitate a tilting of the land to the extent of only five minutes of arc, an amount quite invisible on buildings. But it would, nevertheless, be extremely interesting if any explorer would take the trouble to carefully measure the slopes of the line of masonry in all these ancient buildings, in order to see if there is any indication of any change of slope having occurred. There is only one possible method of noting whether the land near the coast-line is rising or falling, and that is by means of tide-gauges on the west coast of South America, and it is certainly to be hoped that those in charge of them are taking steps to keep such a record as will enable observers in future times thus to obtain the most accurate estimate possible of the movement of the Earth. As to the movements in the interior of the continent, as compared with the coast, I presume the best way of getting at the desired results would be by measurements of vertical angles. Let us hope that the South American surveyors are also keeping this fact in mind, so that by an accurate determination of the vertical angles of some of the highest peaks from the coastline say a hundred years hence, the best possible estimate of this change may be obtainable. I have, I fear, spoken too long, but my excuse is that I have been provoked to it by my late President, whom I could never disobey. (Markham 392-393)

From these remarks, it is clear that it was Markham himself who first suggested that the Andes had been uplifted after the building of the city:

Some miles from the southern shores of Lake Titicaca, once actually on the shore, there are the ruins of a great city, now called Tiahuanacu. In the time of the Incas it was the same ruin as it is now, its origin and history absolutely unknown, and myths were invented to account for the numerous stone statues. The ruins show very advanced proficiency in the masonic art, and there are monoliths which have been conveyed from great distances. The size of these cut and carved stones is unequalled in any other part of the world except Egypt. There must necessarily have been a very large population, and an immense food-supply. The question how a region where corn will not ripen can have been selected as a site for a great city is a problem which seems well worthy of study.

The site is over 12,000 feet above the sea. Cuzco is at an elevation of 11,000 feet. If the Tiahuanacu city flourished when the Andes were still 1000 feet lower, the problem would be solved. The Cordilleras of the Andes, if the grandest and most important mountains in the world, from their vast extent and productiveness, are the most modern. The conclusion of Dr. Reiche is that they had no existence even in so late a geological period as the cretaceous, and there seems to be evidence that the upheaval has been comparatively rapid. Darwin tells us that, in the neighbourhood of Valparaiso there has been a recent rise of 1200 feet. He also found remains, consisting of maize cobs and cotton twine, on the summit of the island of San Lorenzo, proving that the land has risen 80 feet within a time when human inhabitants were cultivating the ]and. This calls to mind the Huarochiri myth which declares that:

“When Viracocha was here our land was Yunca.”

That is to say, that their tradition tells them that, in the golden age, the Huarochiri hills, at no great distance from Darwin’s point of observation at San Lorenzo, were formerly valleys like those on the coast called Yunca. Again, there are numerous skeletons of gigantic ant-eaters in the deserts of Tarapaca. I have presented two to the British Museum. No forests to support them could have existed in Tarapaca, while the Andes were at anything like their present height. These and other interesting geographical problems invite further study and exploration in the Titicaca region. Several lofty peaks are still neither ascended nor measured. (Markham 386-387)

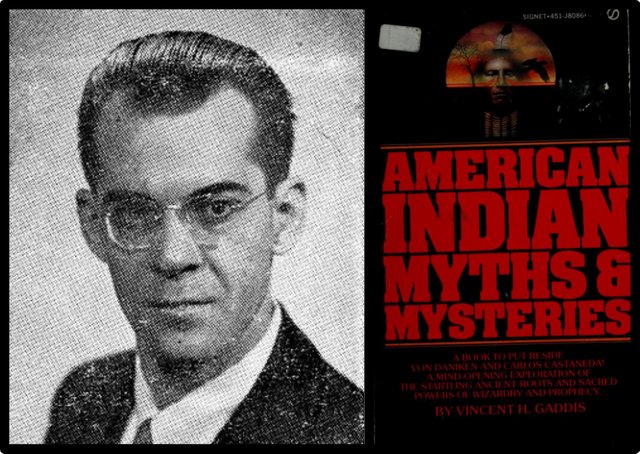

As recently as 1977, the American author Vincent Gaddis, the Fortean writer who popularized the idea of the Bermuda Triangle, revived Markham and Darwin’s hypothesis as the simplest solution to the mysteries of Tiwanaku:

The most likely solution to the Tiahuanaco enigma is startling and runs counter to orthodox geological and archaeological theories. It is simply that the mountain[s] had risen considerably after the city had been built. The conservative view is that mountain making is a slow, continuous process during hundreds of thousands of years. the idea that a large land mass can be raised thousands of feet in a short time, geologically speaking, is rejected. Tiahuanaco challenges this dogma ... At some period in the past, the entire Titicaca plateau was at or below sea level with its lakes forming part of a sea gulf. At a later time, perhaps, a city was built and surrounded by farming terraces on the elevations around it. There was a final upheaval and the plateau was raised to its present height, making the city uninhabitable. (Gaddis 44 ... 45)

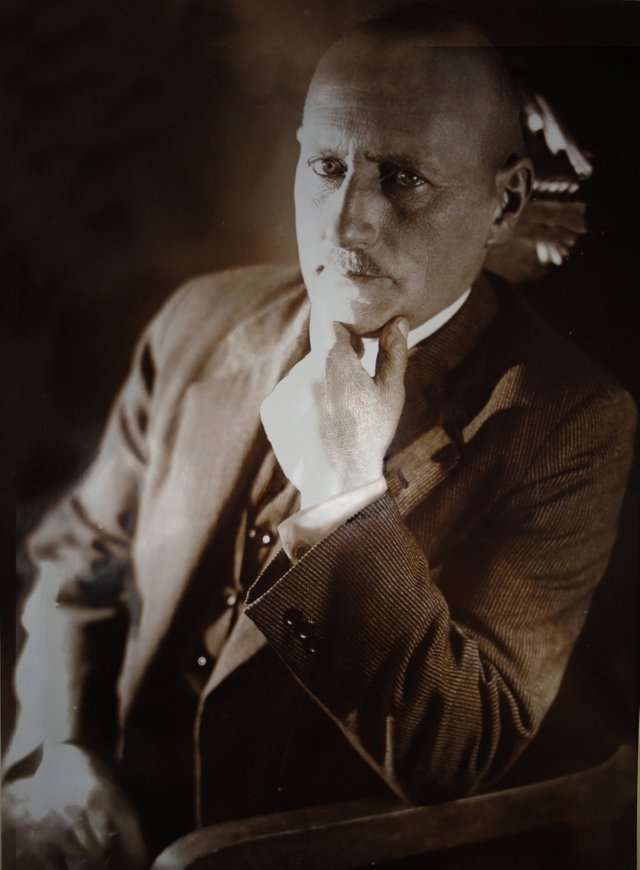

Arthur Posnansky

Velikovsky’s next source is the Austrian scientist mentioned above. Arthur Posnansky was a man of many talents. He was by turns soldier and war hero, naval engineer, builder, urban planner, filmmaker, photographer, researcher, writer, historian, miner, explorer, entrepreneur, paleontologist, anthropologist and archaeologist. His only formal training was in naval engineering, and it was in this capacity that he had his first taste of travel. In 1896, when he was 23, he emigrated to South America and explored the Bolivian and Brazilian Amazon. He fought for Bolivia, his adoptive country, in the Acre War of 1899-1903. In the campaign, Posnansky was wounded and captured by the Brazilians, but he escaped and took refuge in Europe, before eventually rejoining his brothers-in-arms.

His passion for archaeology was awakened when he began to research and explore Bolivia’s Incan and pre-Incan archaeological sites in the early years of the 20th century. Posnansky is best remembered today for his theories on Tiwanaku. In his final work, Tiahuanacu, the Cradle of the American Man, he argued that the city was constructed around 15,000 BCE and marked the beginning of civilization in the Americas. The first two volumes of this book were published in Spanish and English in 1945, one year before Posnansky’s death. An earlier edition of Volume 1 had actually appeared as early as 1914 under the title Una Metrópoli Prehistórica en la América del Sud [A Prehistoric Metropolis in South America]. Volumes 3 and 4 were published posthumously in 1957. The work remains an invaluable source of data—photographs, drawings, maps, descriptions—on the archaeological site. Few modern archaeologists, however, would go as far as Velikovsky, who refers to Posnansky as an authority on the site (Velikovsky 76).

Posnansky’s views on the origins of civilization and the peopling of the globe are quite unorthodox:

Posnansky sticks to the theory according to which humanity originated in the Polar Region, that there a mild appeared first thus allowing mammalians to live and develop; the Polar Regions were called Arctic and Antarctic. From them man spread gradually over the Earth, even before the Glacial period, moving toward the Equator and establishing themselves in more favorable regions situated in the high plateaus, as the ones of Tibet, Mexico and the Andes. (Posnansky 3:7, Anonymous Introduction)

But Velikovsky is only interested in his opinions on the recentness of the geological changes that led to the abandonment of the city. Posnansky hypothesis that Tiwanaku declined due to malign climatic conditions is generally accepted today, but what Posnansky imputes to adverse geological changes, modern archaeologists impute to climate change:

But nothing endures forever. Great civilizations are destroyed, and new ones are engendered, sometimes inferior, occasionally superior to those that went before. Thus it befell the metropolis of Tiahuanacu. Having reached in very remote times almost the apogee of the civilization then attainable, it declined rapidly because of adverse geological changes. Since the surroundings were impaired, malign climatic conditions arose. Climatic aggression put a walking staff into the hands of the dwellers upon the Altiplano, forcing them to go on and on, until they found suitable locations where they could again establish themselves and enjoy the fruits of their labors. These emigrants then, carrying with them their cultural baggage, spread throughout all those parts of the hemisphere which still remained unaffected by the “climatic aggression,” disseminating as they went their enlightenment and beliefs. (Posnansky 1:2)

In support of his hypothesis Posnansky adduces several pieces of evidence that Lake Titicaca was on the coastline in the recent past:

Water Line

The western part of the continent of South America, or, rather, the coasts of Southern Peru and Chile, show for the moment, as has been pointed out above, a rising movement which carries the mountain ranges with it along with the Andean Altiplano which they flank and surround. The marks of the old water line on all of this coast are seen to be high in certain parts, hundreds of meters above the present level; in other parts they are not so high, traces having been erased in the upper region through erosion. The water line visible at the present time in the Coastal heights is rather recent, since otherwise its last traces would have disappeared through erosion brought about by the continual changes in temperature, wind, water and other factors, as has occurred in the more elevated regions. (Posnansky 1:18-19)

Marine Fauna

That Lake Titicaca is what remains of a great suspended body of ocean water, is evinced by the fact that the fauna of the lake—today completely degenerated— is very similar to that which exists in the sea. (1:28)

As early as 1876, Alexander Agassiz demonstrated the existence of a marine crustaceous fauna in Lake Titicaca. (1:29)

Velikovsky lifts this quotation out of Posnansky and passes it off as his own, as though he came across it while independently researching the writings of Alexander Agassiz, son of the famous proponent of the Ice Age Louis Agassiz. The only change he makes is to alter As early as 1876 to As long ago as 1875. The change of date, however, does suggest that Velikovsky took the trouble to look up Agassiz’ original paper, for, though the paper was published in 1876, Agassiz’ expedition to South America took place in 1875. The citation refers to this passage in Agassiz:

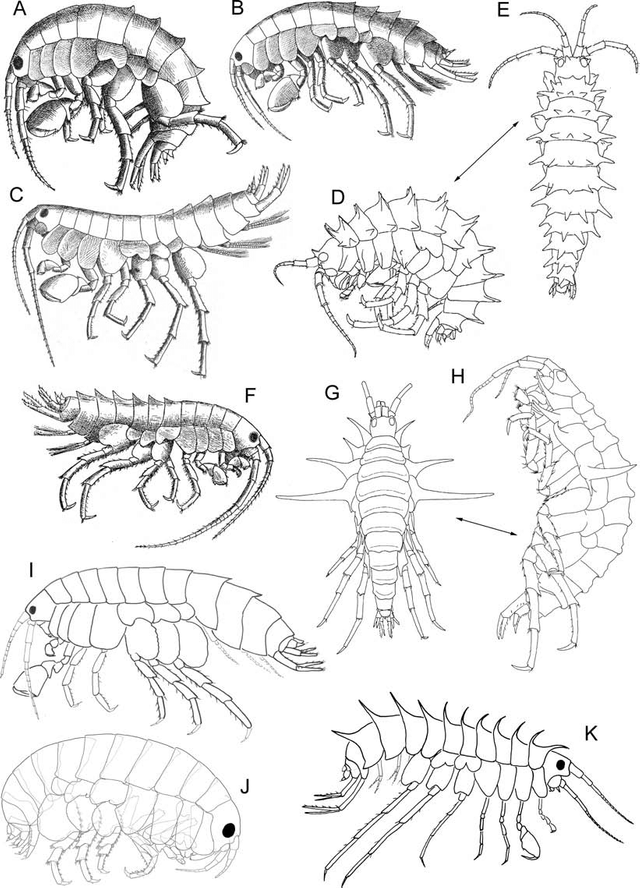

The Crustacea, on the other hand, belong mainly to the Orchestiadæ, forms which thus far have not been found in fresh water at all: their nearest allies are nearly all marine. (Agassiz 287)

Chemistry

The Chemical composition of the water of Lake Titicaca is still similar to that of the sea, as is to be seen in the analysis which follows. (1:29)

Recent Deposits

Evident signs of the existence of such lakes are noted when one travels by airplane. Their last remains are the two lakes of Titicaca and Poopó, the lake and salt bed of Coipaza, the salt beds of Uyuni, and numerous others farther south ... where there is dearly seen the sediment of an enormous lake with but slightly brackish water, in fact almost potable. At this point, at about a meter under the alluvium ... a soft layer of fresh water lime has been found extending over approximately one hundred square kilometers. This stratum is full of characteristic molluscs, such as Paludestrina and Ancylus, which shows that it is, geologically speaking, of relatively modern origin. (1:23)

The phrase geologically speaking covers quite a protracted period of time. The genera Paludestrina and Ancylus are found throughout the Cenozoic Era, which began 66 Mya.

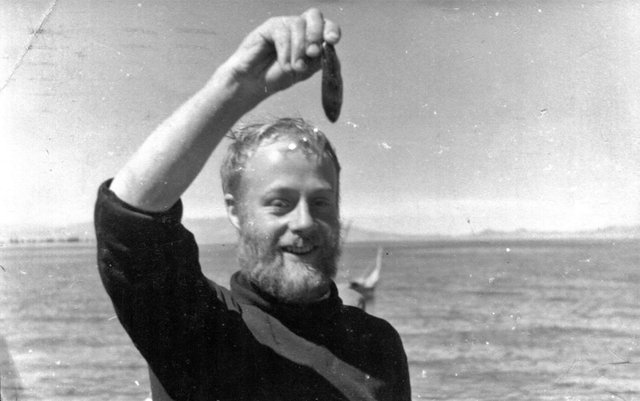

H P Moon

In passing, Velikovsky also quotes the Manchester-born biologist Harold Philip Moon in support of the theory that Lake Titicaca was only recently on the sea. Moon worked in the Fisheries Laboratory at the University of Southampton, and was later Assistant Lecturer in Zoology at the University of Manchester. In 1937, he took part in the Percy Sladen Expedition to Lake Titicaca (Gilson 533-538). After the war, he became Professor of Zoology at the University of Leicester:

Once Tiahuanacu was at the water’s edge; then Lake Titicaca was ninety feet [20 m] higher, as its old strandline discloses. But this strand line is tilted and in other places it is more than 360 feet above the present level of the lake. There are numerous raised beaches; and stress was put on “the freshness of many of the strandlines and the modern character of such fossils as occur.” (Velikovsky 76-77)

In its original context, this quotation is not as supportive of Velikovsky’s catastrophist thesis as one might have surmised. The strandlines Moon is referring to are not marine but lacustrine coastlines:

From the numerous examples quoted there is abundant evidence for the existence in geologically recent times of very much more extensive lake systems in the Altiplano than exist to-day. It is probable that the strandlines referred to by so many authors all represent various levels of the two lakes, Minchin and Ballivian. In 1937 the author examined two raised beaches at Pazña, above Lake Poopó. One of these beaches was 30 metres, the other 28 metres above the present lake. Both these beaches probably represent stages in the gradual dwindling of Lake Minchin or Ballivian.

The freshness of many of the strandlines and the modern character of such fossils as occur indicate that the two lake systems described above were recent. It is only possible to give them an approximate date, but they were probably associated with the Quaternary glaciation of the district. The great extent of the two lakes suggests that they were inter-glacial and fed by water from the melting ice of retreating glaciers. Whether they represent two separate inter-glacial periods or fluctuations in a single inter-glacial interval, it is impossible to say. There is, therefore, a time gap between the formation of the Altiplano in the Miocene, and the formation of glacial lakes in the Quaternary. Throughout that period the Altiplano was probably enclosed and admirably suited for the accumulation of the drainage into lakes. Lakes would almost certainly be present, one system succeeding another, but owing to the friable nature of lacustrine deposits, few traces have been left. (Moon 32)

Just three pages later, Moon actually considers and rejects the theory that Lake Titicaca is of marine origin:

So far the Altiplano drainage systems, both recent and ancient, have been considered as a perfectly normal sequence of freshwater lakes and streams. The history of the Altiplano is, however, complicated by the theory of the marine origin of the fauna of Titicaca and Poopó ...

The idea that Titicaca is an elevated arm of the sea and that Hyalella and Orestias represent marine relicts can have no foundation in the light of more recent work. The wide distribution in South America of the genus Hyalella is sufficient to remove any such possibilities. In the case of Orestias there is no evidence of close affinities with the marine genera of the family Cyprinodontidae, to which the genus belongs. Indeed, most genera of the family are fresh-water, a limited number being brackish-water or marine forms.

Moreover, even supposing that Hyalella and Orestias were marine relicts, there is no geological evidence to support the idea that Titicaca is an elevated lagoon of the sea. If this were the case, we would expect to find Tertiary marine deposits in the neighbourhood of the lake, and this is not the case. If a marine inlet ever was raised up in this region, it was almost certainly filled in by detritus during the peneplanation following the first period of uplift. (Moon 35-36)

None of this is mentioned by Velikovsky, who is satisfied that the case has been proven:

Sometime in the remote past the entire Altiplano with its lakes rose from the bottom of the ocean. At some other time point a city was built there and terraces were laid out on the elevation around it; then in another disturbance the mountains were thrust up and the area became uninhabitable. (Velikovsky 77)

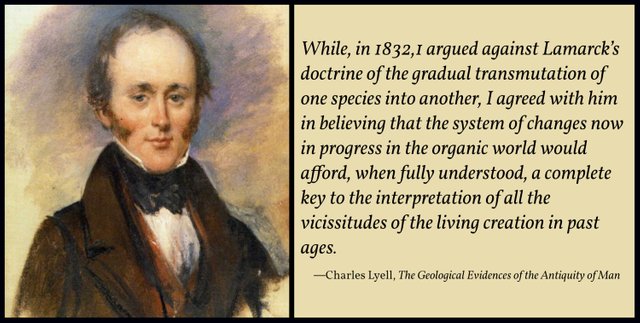

Charles Lyell

The Scottish geologist Charles Lyell was one of the 19th century’s leading proponents of the Doctrine of Uniformitarianism. Like Posnansky, he was not formally trained as a geologist, but unlike Posnansky he is still considered today an authority on the subject. His Principles of Geology did for Uniformitarianism what Genesis did for Creationism. He is one of the last sources we would expect Velikovsky to cite:

The barrier of the Cordilleras that separates the Altiplano from the valley to the east was torn apart and gigantic blocks were thrown into the chasm. Lyell, combating the idea of a universal flood, offered the theory that the bursting of the Sierra barrier opened the way for a large lake on the Altiplano, which cascaded down into the valley and caused the aborigines to create the myth of a universal flood. (Velikovsky 77)

The citation is to Volumes I and III of the Principles of Geology:

In speculating on catastrophes by water, we may certainly anticipate great floods in future, and we may therefore presume that they have happened again and again in past times. The existence of enormous seas of fresh-water, such as the North American lakes, the largest of which is elevated more than six hundred feet above the level of the ocean, and is in parts twelve hundred feet deep, is alone sufficient to assure us, that the time will come, however distant, when a deluge will lay waste a considerable part of the American continent. No hypothetical agency is required to cause the sudden escape of the confined waters. Such changes of level, and opening of fissures, as have accompanied earthquakes since the commencement of the present century, or such excavation of ravines as the receding cataract of Niagara is now effecting, might breach the barriers. Notwithstanding, therefore, that we have not witnessed within the last three thousand years the devastation by deluge of a large continent, yet, as we may predict the future occurrence of such catastrophes, we are authorized to regard them as part of the present order of Nature, and they may be introduced into geological speculations respecting the past, provided we do not imagine them to have been more frequent or general than we expect them to be in time to come. (Lyell I:89)

Supposed Effects of the Flood

They who have used the terms ante-diluvian and post-diluvian in the manner above adverted to, proceed on the assumption that there are clear and unequivocal marks of the passage of a general flood over all parts of the surface of the globe. It had long been a question among the learned, even before the commencement of geological researches, whether the deluge of the Scriptures was universal in reference to the whole surface of the globe, or only so with respect to that portion of it which was then inhabited by man. If the latter interpretation be admissible, the reader will have seen, in former parts of this work, that there are two classes of phenomena in the configuration of the earth’s surface, which might enable us to account for such an event. First, extensive lakes elevated above the level of the ocean; secondly, large tracts of dry land depressed below that level. When there is an immense lake, having its surface, like Lake Superior, raised 600 feet above the level of the sea, the waters may be suddenly let loose by the rending or sinking down of the barrier during earthquakes, and hereby a region as extensive as the valley of the Mississippi, inhabited by a population of several millions, might be deluged. (Lyell III:270)

Lyell does not actually mention South America’s Altiplano or the bursting of the Sierra barrier in any editions of the Principles of Geology that I have examined (1st, 2nd, 12th). I am at a loss to explain Velikovsky’s text, unless he is simply applying to South America what Lyell wrote about Lake Superior. This is certainly a valid construction to put on Lyell’s words, but Velikovsky’s manner of expressing it leads one to believe that Lyell specifically mentioned the catastrophic draining of a large lake on the Altiplano.

As this post is becoming too large, this is a good place to take a break.

References

- Alexander Agassiz, Hydrographic Sketch of Lake Titicaca, Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Volume 11, Pages 283-292, AAA&S, Cambridge, Massachusetts (1876)

- John Barrett (Director General), Bulletin of the Pan American Union, Volume 32, Government Print Office, Washington, DC (1911)

- Hans Schindler Bellamy, Built before the Flood: The Problem of the Tiahuanaco Ruins, Faber and Faber, London (1947)

- Charles Darwin, Journal of Researches, New Edition, John Murray, London (1852)

- Charles Darwin, Geological Observations on the Volcanic Islands and Parts of South America Visited During the Voyage of H.M.S. ‛Beagle’, Second Edition, Smith, Elder, & Co, London (1876)

- Vincent H Gaddis, American Indian Myths and Mysteries, A Signet Book, New American Library, New York (1978)

- H Cary Gilson, The Percy Sladen Expedition to Lake Titicaca, 1937, The Geographical Journal, Volume 91, Number 6, Pages 533-538, The Royal Geographical Society, London (1938)

- Frank C Hibben, Treasure in the Dust: Exploring Ancient North America, J B Lippincott, Philadelphia (1951)

- Ellsworth Huntington, Climatic Pulsations, Geografiska Annaler, Volume 17, Supplement, Pages 571-608, Swedish Society for Anthropology and Geography, Stockholm (1935)

- Charles Lyell, Principles of Geology, First Edition, Volume 2, Volume 3, John Murray, London (1830-33)

- Charles Lyell, Principles of Geology, 12th Edition, Volume 1, Volume 2, John Murray, London (1875)

- Clements Markham, The Land of the Incas and Discussion, The Geographical Journal, Volume 36, Number 4, The Royal Geographical Society, London (1910)

- Clements Markham, The Incas of Peru, Smith, Elder, and Co, London (1910)

- Harold Philip Moon, The Geology and Physiography of the Altiplano of Peru and Bolivia, Transactions of the Linnean Society of London, 3rd Series, Volume 1, Issue 1, Pages 27-43, London (1939)

- Arthur Posnansky, Tiahuanacu, the Cradle of the American Man, Volume 1, Volume 2, Volume 3, Volume 4, J J Augustin, New York (1945, 1957)

- Immanuel Velikovsky, Earth in Upheaval, Pocket Books, Simon & Schuster, New York (1955, 1977)

Image Credits

- The Sun Gate, Tiwanaku: © Sasha India (photographer), Creative Commons License

- South Peru and North Bolivia: Clements R Markham, South Peru and North Bolivia, Including the Rubber Yielding Montaña (cropped, adapted), Royal Geographical Society, London (1910), Public Domain

- Clements R Markham: Elliott & Fry (photographers), National Portrait Gallery, London, Creative Commons License

- Leonard Darwin: Bain News Service (publisher), George Grantham Bain Collection, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, Public Domain

- Vincent Gaddis: Anonymous Photograph, Public Domain : American Indian Myths and Mysteries, © Signet (cover art), Fair Use

- Arthur Posnansky: Mhuyustus (photographer), Public Domain

- Lake Titicaca: © Luis Fernando Troncoso Joffré (photographer), Creative Commons License

- Talitrus saltator (A Sandhopper): © Arnold Paul (photographer), Creative Commons License

- Harold Philip Moon at Lake Titicaca: The Royal Geographical Society, Fair Use

- The Hyalella Species-Flock of Lake Titicaca: José A Jurado-Rivera et al, Morphological and Molecular Species Boundaries in the Hyalella Species-Flock of Lake Titicaca (Crustacea: Amphipoda), Figure 1, After Drawings by Chevreux, Coleman & González, Weckel, and Faxon, Creative Commons License

- Charles Lyell: Alexander Craig (artist), Glasgow (1840), Public Domain