Whales in the Mountains is the sixth and final section of Chapter IV of Immanuel Velikovsky’s Earth in Upheaval. This section is concerned with the discovery of marine deposits and animal remains in inland and mountainous regions.

Michigan

Velikovsky begins in the vicinity of the Great Lakes of North America:

In bogs covering glacial deposits in Michigan, skeletons of two whales were discovered. Whales are marine animals. How did they come to Michigan in the postglacial epoch? Whales do not travel by land. Glaciers do not carry whales, and the ice sheet would not have brought them to the middle of a continent. Besides, the whale bones were found in post-glacial deposits. Was there a sea in Michigan after the glacial epoch, only a few thousand years ago? (Velikovsky 42)

Velikovsky’s source for this claim is Carl Owen Dunbar’s Historical Geology, a work that has already been cited in this chapter. Dunbar, however, is not at all disconcerted by the discovery:

When the ice had wasted back far enough to free the St. Lawrence Valley, the region was still so much depressed that marine water spread up the St. Lawrence and into the Champlain Valley and probably into Lake Ontario, depositing a layer of blue clay with abundant shells of an arctic molluscan fauna. This is the Leda clay, so called for a small but characteristic clam. The recent discovery of two whale skeletons in bogs above the glacial deposits in Michigan indicates that for a brief time the sea was directly connected with the Pleistocene Great Lakes. Marine shells and the bones of whales have been found in the Leda clays at least 500 feet above sealevel at the Vermont-Quebec boundary, nearly but not quite up to the Lake Ontario level at Kingston, and at about 600 feet in the Montreal-Quebec area. The postglacial upwarp thus indicated is probably a minimum measure of the depression caused by the ice. (Dunbar 453)

Velikovsky also cites James Dwight Dana’s Manual of Geology in connection with the discovery of whale bones 440 feet [134 m] above sea level north of Lake Ontario. Note that the footnote reference has been inserted in the wrong place—probably a simple printing error:

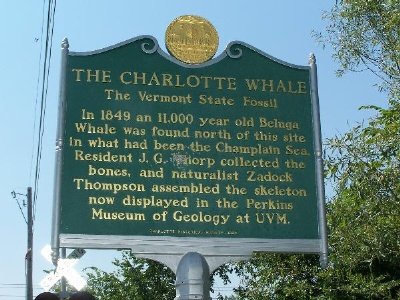

Moreover, this great arm of the sea, 500 to 600 feet [150-180 m] in depth of water at Montreal, and 700 to 900 feet [210-275 m] in Lake Champlain, besides nurturing Mollusks, was a sporting ground for Seals, Morses, and Whales. Bones of the Humpbacked Whale, Megaptera longimana, have been reported by Dawson as found 440 feet above the sea in the County of Lanark, 31 miles [50 km] north of the outlet of Lake Ontario; and remains of the White Whale, or Beluga (a species related to the Porpoise), both along the St. Lawrence, and on the borders of Lake Champlain, in Vermont, where a skeleton was found. The latter is the Delphinapterus leucas (= catodon) or “White Whale,” the Beluga Vermontana of Z. Thompson. These two Arctic species, the Humpbacked Whale and Beluga, are now occasionally met with in St. Lawrence River. (Dana 983)

Like Dunbar, Dana is not put out by these signs of large-scale subsidence of the land. During the Last Glaciation, the land was depressed by the overlying ice sheet. When the latter was removed, the sea encroached upon the land before the land slowly rebounded to its present altitude. But while Velikovsky accepts this argument, he finds the evidence impossible to reconcile with Uniformitarianism:

In order to account for whales in Michigan, it was conjectured that in the post-glacial epoch the Great Lakes were part of an arm of the sea. At present the surface of Lake Michigan is 582 feet [177 m] above sea level ... To account for the presence of whales in the hills of Vermont and Montreal, at elevations of 500 and 600 feet, requires the lowering of the land to that extent. Another solution would be for an ocean tide, carrying the whales, to have trespassed upon the land. In either case herculean force would have been required to push mountains below sea level or to cause the sea to irrupt, but the latter explanation is clearly catastrophic. Therefore the accepted theory is that the land in the region of Montreal and Vermont was depressed more than 600 feet by the weight of ice and kept in this position for a while after the ice melted. (Velikovsky 42 ... 43)

Velikovsky’s coup de grâce is the discovery of tree stumps and deep riverine canyons off the shores of Nova Scotia and New England:

But along the coast of Nova Scotia and New England stumps of trees stand in water, telling of once forested country that became submerged. And opposite the mouths of the St. Lawrence and the Hudson rivers are deep canyons stretching for hundreds of miles into the ocean. These indicate that the land became sea, being depressed in post-glacial times. Then did both processes go on simultaneously, in neighboring areas, here up, there down? (Velikovsky 43)

Velikovsky does not cite any source for these discoveries, though they are easy to confirm. Douglas Wilson Johnson’s short paper Botanical Evidence of Coastal Subsidence (1911) may have been the source for the tree stumps. Velikovsky cites another of Johnson’s works in Chapter VII. In 1911, Johnson took part in the Shaler Memorial Expedition, an elaborate and exhaustive study of the whole shoreline of Eastern North America from Prince Edward Island to the Florida keys (Bucher 202). But any number of other papers on the subject could also be cited. For example:

Drowned forests on the seacoast of New England and Nova Scotia have long been objects of scientific curiosity. Well preserved stumps and logs of familiar modern species seemed to prove recent sinking of the land. Because the drowned forests occurred in a region known to have been strongly upwarped during the removal of the last ice sheet, the subsequent sinking was thought to be a reverse movement, possibly the delayed flattening of what had been a peripheral bulge around the depressed ice-covered area. (Lyon & Goldthwait 605)

The Hudson Canyon is mentioned again in Chapter VII, where Velikovsky’s source is an article by Maurice Ewing in the National Geographic Magazine. This article is still hidden behind a paywall, but I do not believe it mentions the St Lawrence River.

The Gulf States

Velikovsky now turns his attention to the Gulf States in America’s Deep South, where there are similar signs of largescale submergence and emergence of the land. Here, however, the formation of ice sheets and their subsequent removal cannot be invoked to explain the dramatic changes in the relative levels of land and sea:

A species of Tertiary whale, Zeuglodon, left its bones in great numbers in Alabama and other Gulf States. The bones of these creatures covered the fields in such abundance and were “so much of a nuisance on the top of the ground that the farmers piled them up to make fences.” There was no ice cover in the Gulf States; then what had caused the submergence and emergence of the land there? (Velikovsky 43)

The quotation is taken from Common-Sense Geology by George McCready Price, a Canadian creationist whom Velikovsky cited in Chapter II and will cite in forthcoming chapters of Earth in Upheaval. As though to forestall those critics who would not consider McReady Price a reliable source, Velikovsky also quotes Reginald Aldworth Daly, a Canadian geologist with impeccable academic credentials:

Not long ago in a geological sense, the flat plain from New Jersey to Florida was under the sea. At that time the ocean surf broke directly on the Old Appalachian Mountains ... The wedge-like mass of marine sediments was then uplifted and cut into by rivers, giving the Atlantic Coastal Plain of the United States. Why was it uplifted? To the westward are the Appalachians. The geologist tells us of the stressful times when a belt of rocks, extending from Alabama to Newfoundland, was jammed, crumpled, thrust together, to make this mountain system. Why? How was it done? In former times the sea flooded the region of the Great Plains from Mexico to Alaska, and then withdrew. Why this change?” (Daly 1926:90)

Further evidence of marine deposits that were discovered inland and at high altitude is taken from Richard Foster Flint’s Glacial Geology and the Pleistocene Epoch, a work that was cited in Chapter II in the section entitled The Erratic Boulders. Flint dates these deposits to the last interglacial episode rather than to the postglacial epoch (Flint 292).

Velikovsky asks an important question:

The change in land elevation in the region previously covered by ice is ascribed to the removal of the ice cover that weighed down the earth's crust; but what changed the elevation of other areas outside the ice cover? If the land slowly rose when freed from ice and carried the bones of whales to the summits of hills, why did the neighboring land subside miles deep, as the undersea canyons indicate? (Velikovsky 44)

In response, Velikovsky concludes this chapter with a quotation from another of Reginald Aldworth Daly’s works, The Changing World of the Ice Age:

The Pleistocene history of North America holds ten major mysteries for every one that has already been solved. (Daly 1934:11)

In this series of lectures, Daly discusses in some detail the subjects of isostasy and eustasy. He explains how one part of a continental mass can subside to compensate for the rising of a neighbouring part of the same mass. For example, at least some of the postglacial subsidence observed in France was compensatory for the plastic rise of Fennoscandia in the same interval of time (Daly 1934:140). Similar compensatory subsidence could account for at least some of the interglacial changes in the relative levels of land and sea in the Gulf States.

Summing Up

In this section, Velikovsky has continued to amass evidence that geomorphological changes typical of glaciation tend to be of a much greater magnitude than those that occur between ice ages and operate on much shorter timescales. These observations alone give the lie to the gradualistic principle of Uniformitarianism: The present is the key to the past (Geikie 161, 171).

References

- Walter H Bucher, Biographical Memoir of Douglas Wilson Johnson, National Academy of Sciences, Washington, DC (1946)

- Reginald Aldworth Daly, Our Mobile Earth, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York (1926)

- Reginald Aldworth Daly, The Changing World of the Ice Age, Yale University Press, New Haven CT (1934)

- James Dwight Dana, Manual of Geology: Treating of the Principles of the Science with Special Reference to American Geological History, for the Use of Colleges, Academies, and Schools of Science, Fourth Edition, American Book Company, New York (1895)

- Carl Owen Dunbar, Historical Geology, John Wiley & Sons, Inc, New York (1949)

- Maurice Ewing, New Discoveries on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, National Geographic Magazine, Volume 96, Number 5, pp 611-640, National Geographic Society, Washington, DC (1949)

- Richard Foster Flint, Glacial Geology and the Pleistocene Epoch, John Wiley & Sons, Inc, New York (1947)

- Archibald Geikie, Landscape in History and Other Essays, Macmillan and Co, Ltd, London (1905)

- Douglas Wilson Johnson, Botanical Evidence of Coastal Subsidence, Science, New Series, Volume 33, Number 843, pp 300-302, The Science Press, New York (1911)

- Charles J Lyon, James W Goldthwait, An Attempt to Cross-Date Trees in Drowned Forests, Geographical Review, Volume 24, Number 4, pp 605-614, The American Geographical Society of New York, New York (1934)

- George McReady Price, Common-Sense Geology, Pacific Press Publishing Association, Oakland CA (1946)

- Immanuel Velikovsky, Earth in Upheaval, Pocket Books, Simon & Schuster, New York (1955, 1977)

Image Credits

- The Charlotte Whale, Vermont: Perkins Geology Museum, Vermont, © 2020 FossilEra, Fair Use

- Gravel Pit in Lanark County, Ontario: © Christopher Brett, Fair Use

- The Charlotte Whale: © The University of Vermont, Fair Use

- Hudson Canyon: © Wildlife Conservation Society, Fair Use

- Zeuglodon (Basilosaurus): Fossil of Basilosaurus cetoides, Smith Hall, Alabama Museum of Natural History, © Skusnr, Creative Commons License

We're in this together.🌞🌄 Resteem to our profile!

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit