A panel of retired U.S. military officials from the CNA military advisory group have joined international organizations in warning about the connections between water stress and conflict.

Water stress is defined as a shortage of fresh water and while it does not lead directly to conflict, a pattern has emerged demonstrating how water can act as the spark that inflames otherwise unstable situations.

Loss of rural livelihoods

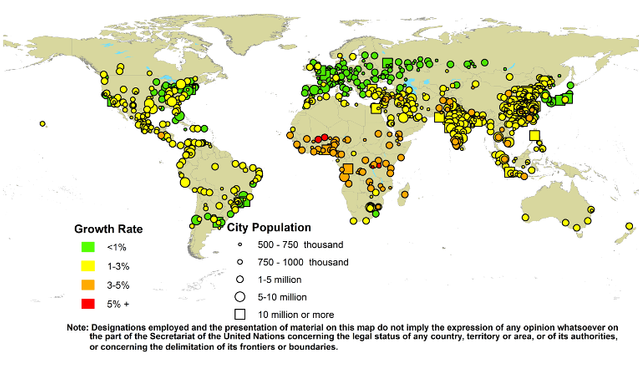

Water stress in rural agricultural communities places limits on the ability of local populations to produce their own food and provide for their families. Across the Sahel region, and in countries such as India, Syria, and Bolivia this has encouraged an influx of urban migration.

Growth rates of urban agglomerations by size class, 2014-2030. UNPD 2017

Increased urban unemployment

Many of the world's cities are already over-crowded and plagued by a lack of economic opportunity. Further influx of job-seekers from the country side easily overwhelms the existing labor market, and lack of available employment can lead to epidemic sized youth unemployment, as in Syria, Kenya, and Iran.

Increased extremism and localized conflict

Tinder boxes of bored and/or desperate unemployed populations - particularly disproportionately young populations - are vulnerable prey for terrorist recruitment, such as in (Iraq) and Somalia, Nigeria, Chad, and Niger, as well as for localized conflict more generally, such as in Yemen, Mexico, and Kenya.

Global pressure points

Likewise, our global food supply means that agricultural threats posed by water stress in other parts of the world can cause tensions for otherwise unsuspecting local populations. For example, the Russian wildfires in 2010 prompted a ban on grain exports in 2010 and caused the price of bread in Syria to skyrocket.

Syrian men hold up pieces of bread as they protest in Banias on 4 May 2011 in solidarity with compatriots in besieged Deraa. Photograph: Str/AP 2011

International Conflict

Fights over water can quickly span borders, particularly in areas dependent on transnational water flows. International conflict over water has already caused conflict between Iran and Afghanistan and is a major concern when dealing with nuclear powers, such as India and Pakistan.

Water as a weapon of war

Actors in conflicts have increasingly targeted water infrastructure, whether through direct or indirect attempts to render water and food a weapon of war, such as it has become in Yemen, Iraq, and Libya.

Conflict intensifies water insecurity, deepening the crisis and desperation of the local people.

Water cans filled at an aid station in Somalia in March. Maciej Moskwa/NurPhoto, via NY Times

The qualia of thirst

Consider what it feels like to be severely dehydrated. Think about the worst hangover you've ever had. Now imagine there wasn't a faucet or water bottle from which to quench your thirst in the morning. What's worse, there's no Chipotle or even affordable bread to put in your stomach. A friend of mine works in restaurants in New York City. He used to say he thought he worked harder when he was hungover because he was not able to think about anything but the task at hand. Yet, imagine spending days - weeks - months operating in this way; unable to think about anything beyond immediate sensations, environments, and discontents.

It might cause a bit of irritability. And if most of the people around you felt the same way, with no end of the situation in sight, it might make you angry. It might drive you to protest or to riot.

Protesters in Iran. Washington Post 2018

Only the latest example

Iran's former agricultural minister, Issa Kalanari, once said that, if left unchecked, water insecurity in the country would cause conditions so harsh that 50 million Iranians would leave the country altogether.

Iranian politicians responded with short-term, politically expedient solutions, including damming lakes for rural conservative strongholds. David Michel, an analyst at the Stimson Center, told the New York Times that managing water is the government's "most important policy challenge." It is a challenge too important to patch with short-term quick fixes.

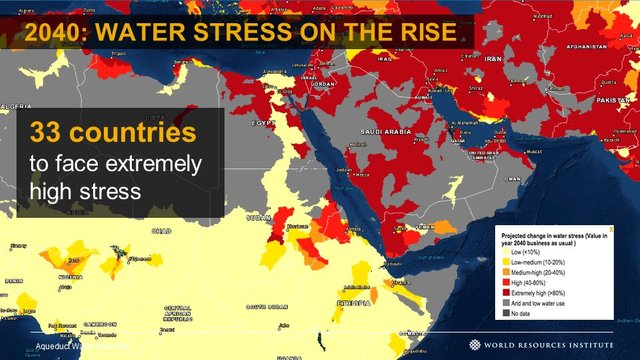

This can be said for government's around the world, particularly those in the 33 countries that the World Resource Institute estimate will experience extremely high water stress in 2040. The impacts of conflict and migration are not contained within borders, however, and this pattern will continue to threaten the security of a large proportion of the global population.

WRI Aqueduct 2017

Recognizing this pattern can be an opportunity

If water stress is a spark for conflict - it could also serve as an indicator as to where and how resources ought to be distributed to prevent the conflagration from occurring in the first place.

Water can be a catalyst. It can be a thing that breaks the system. - Julia McQuaid, deputy director of CNA

Monitoring water scarcity indicators and events could allow experts and humanitarian actors to better strategist where and how to deploy aid or support resources.

Technological advancements are emerging that make anticipating and planning for changes in the hydrological cycle increasing feasible. In addition to WRI's Aqueduct tool, which allows users to map out five risk indicators to better plan for future conditions, artificial intelligence and satellite technologies are emerging that will allow experts to monitor and respond to sudden changes. Here are a couple places to get a taste for these truly awesome projects: Verge, Wired, Digital Trends.

Other research out of MIT has made it possible to isolate the most intense impacts of the changing climate, such as wet-bulb temperature change, enabling strategic preparations to target the most vulnerable areas and/or the most sensitive periods of time. The video below lays out an overview of the findings from the MIT study.

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="Tomorrow's Possibilities

The challenge is for our global market place to keep pace with technology. Trading water from secure areas to insecure ones is most effectively done through the global food trade. Updating and modernizing our agricultural trade networks and agreements could potentially lead to a system where changing water cycles are anticipated by changes in the distribution channels of water-rich crop staples.

This means, of course, preparing in advance and restructuring our food production model to better fit the resources available. In other words, maybe it's time to question business as usual for water intensive farming operations in California and Australia. These areas do not have the ability to rapidly deploy surplus crops to drought-stricken zones.

Vertical farms, 3D-printers, genetically advanced cropping techniques (etc.) are all ways to ensure that local food supplies are not entirely linked to the global markets. These technologies are much easier for developed countries to deploy than developing ones. And it is in developing countries where we find the conditions most vulnerable to water stress.

Food markets are big business - which is why it is so encouraging that the largest agricultural companies, including Cargil, Coca Cola - who trades tons of water, and Dole, are looking for ways to increase the adaptability and sustainability of their business methodologies.

Recognizing the very real threats of water insecurity to stable governance has already proved a valuable pressure for bringing regional governments together to address interdependent resource management challenges. Taking these patterns more seriously in the developed world could allow for increased institutional and technological support in terms of strategy development and accountability. One organization working to efficiently facilitate such negotiations is the Hague Institute for Global Justice, who's water diplomacy team has already assisted in regional dialogues in the Brahmaputra and the Jordan River basins.

Building a comprehensive strategy for adapting to and dealing with increasingly common changes in the global water supply may be a valuable means of protecting national security and international stability.