The Open Shuhada Street Campaign takes place in Hebron, Palestine to commemorate the massacre at the Ibrahimi Mosque and protest apartheid.

HEBRON, PALESTINE — In order to fully understand the reality in Palestine, one must come to terms with the idea that the conquest of Palestine by the Zionists was done with the intent of committing genocide and ethnic cleansing of the native inhabitants of Palestine. This was true when, in 1948, 78 percent of Palestine was conquered and renamed Israel and it was also true when, in 1967, the conquest was completed and Israel took the remaining 22 percent of the country.

The intention was and remains taking over the land and populating it with Jews at the expense of Palestinians. It is true in the villages and in the towns, in the cities and in the countryside. It is crucial to examine how the Zionist regime accomplishes its goals on a case by case basis, and how local Palestinian leaders and grassroots groups resist. One particularly troubling example is the Zionist takeover of the old city of El-Khalil, Hebron, and the actions taken by Youth Against Settlements (YAS), and its leader and cofounder Issa Amro, to resist this takeover.

The sneaky start of the Jewish settlements

Israeli settlers try to stop Palestinian workers on a bulldozer in Hebron preparing the work for a new foundation on Shuhada street, March 18 1997. (AP/Nasser Shiyoukhi)

Hebron lays in the southern part of what is referred to as the West Bank. Other than East Jerusalem, it is the largest and busiest Palestinian city in the West Bank. In April of 1968, less than a year after the city was taken by Israel, Rabbi Moshe Levinger — a student of the ultra-right-wing Zionist rabbi, Tsvi Yehuda Kook — along with a group of Zionist Jewish radicals, decided it was time to settle this ancient city with Jews. They rented the Park Hotel in Hebron for a few days, supposedly intending to celebrate the holiday of Passover. Eighty-eight people celebrated Passover Seder that night in the heart of Hebron, and then refused to leave.

After some negotiations with the Israeli authorities, when it became clear they were not going to leave, Defense Minister Moshe Dayan suggested that they move to the military compound overlooking Hebron. Six weeks later, the settlers agreed to move to the compound, where they remained for the next three years. During this time, the Israeli government was searching for ways to make this messianic dream come true: to build a Jewish city in the heart of the old city of Hebron.

During this waiting period, the settlers, as they became known, received a great deal of support from political figures, including members of the cabinet who visited the new settlement in a show of support. Perhaps the most notable among them was Yigal Alon, who was one of the most important figures in the Zionist labor movement and an admired military commander of 1948.

Eventually, the Israeli government, under the leadership of Labor Prime Minister Golda Meir and Defense Minister Dayan, approved the creation of a Jewish city on Palestinian land adjacent to the heart of the Palestinian town of El-Khalil. This was the city of Kiryat Arba. In March 1970, the Knesset, the Israeli parliament, formally approved the establishment of the settlement Kiryat Arba, allowing the first 50 families, including Levinger and his followers from the Park Hotel, to officially move in.

According to a piece published in 2016 in the Israeli daily Haaretz, at a meeting in then-Defense Minister Dayan’s office, top Israeli officials discussed how to allow the building of Kiryat Arba next to Hebron, knowing that this was a clear violation of international law, particularly Article 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention. According to the report, “This secret document from 1970 has surfaced confirming the long-held assumption that government and military leaders spoke explicitly about how to carry out this deception in the building of Kiryat Arba, next to Hebron.”

The tactic, used many times since, included three stages: Stage One, expropriate land from Palestinians claiming it is for military use; Stage Two, build civilian housing on the military base and then allow Jewish settlers to move in; and Stage Three, recognize it as a legitimate Jewish settlement. This set a precedent for the creation of facts on the ground that would become the model for the expansion of the settlement enterprise in the West Bank. The importance of this document is that it lays to rest the claim that somehow the settlements in the West Bank were done by right-wing governments and without consensus.

Levinger and his settler movement, which was named Gush Emunim, would go on to spearhead settlements across the West Bank, sparking clashes with Palestinians and the Israeli army but then receiving complete government recognition and full support. Today, what used to be the West Bank is called Judea and Samaria and it is filled with established Jewish towns, which represent a centerpiece of Zionist ideology.

The takeover of Hebron’s Old City and the YAS resistance

Israeli soldiers arrest a Youth Against Settlements protester demanding the reopening of Shuhada Street in the West Bank city of Hebron, Feb. 27, 2015. Israel closed Shuhada Street for Palestinians in 1994 after an Israeli killed 29 Palestinians and wounded over a 100 praying in a mosque. (AP/Nasser Shiyoukhi)

While Kiryat Arba itself is only adjacent to the Old City of Hebron, the settlers from Kiryat Arba eventually began taking over parts of the Old City itself using the same familiar tactic. In 1979, a group of women and children entered the Daboya building, or Beit Hadassah. They camped out at the building for about one year before being recognized and allowed to build and formally live there. Menachem Begin who was Prime Minister at the time would not allow them to be removed stated that, “Hebron is also Israel, I will not allow for any place in Israel to be ‘Judenrein.'” They were eventually joined by their husbands in what became known as the Beit Hadassah settlement.

In 1984 settlers began placing caravans on land in Tel-Rumeida, once again with the protection of the Israeli army. This too eventually became an official settlement as settlers took over Palestinian homes, made them their own, and a military post was erected near these homes. Tel-Rumeida, which easily qualifies to be in the top ten most beautiful spots in Palestine, is a hill that overlooks the old city of Hebron. It sits upon a great deal of archaeological treasure that dates to Roman times and even earlier periods. The hill is covered in ancient olive trees that, judging by the width of their trunks, are over a thousand years old. It is no wonder, then, that the Israeli settlers had coveted that hill.

Their efforts to take the hill were partially blocked, however, thanks to the efforts of YAS and in particular its cofounder Amro. Though many settlers had been able to take over homes on Tel-Rumeida, Amro was able to salvage the hill by renting the home of a Palestinian family into which Israeli settlers were already preparing to enter. He had rented the house from the owners, who were absent yet still had the deeds of ownership to the home, and — after a protracted dispute with the settlers and the Israeli authorities, in what was an unprecedented development — he was able to take possession of the house and turn it into the YAS center.

The center is constantly invaded by soldiers and settlers who would do almost anything to get rid of the center and the YAS activists. But so far, thanks to international recognition and appreciation for the work they do and their persistent non-violent actions and civil disobedience campaigns, the hill has not fallen into enemy hands.

The view of the old city of Hebron and the Ibrahimi Mosque from Tel-Rumeida. (Photo: Miko Peled)

The impact: from everyday life to the Ibrahimi Mosque slaughter

The Avraham Avinu settlement is built on what is known as Dewwar Elhesbeh – in what is now the closed fruit and vegetable market. It is the largest settlement inside the city of Hebron, located in the heart of the Old City between Shuhada Street and the main street of the Casbah. The windows from settlers’ houses look out on the street below and the settlers throw trash, excrement and heavy objects down to the street, forcing the municipality to install protective nets to ensure safety for Palestinians walking along the street. This forced several areas within the market to shut down entirely and many of them have become enormous trash dumps.

The old market — Israeli settlers living upstairs made it impossible for life to continue. (Photo: Miko Peled)

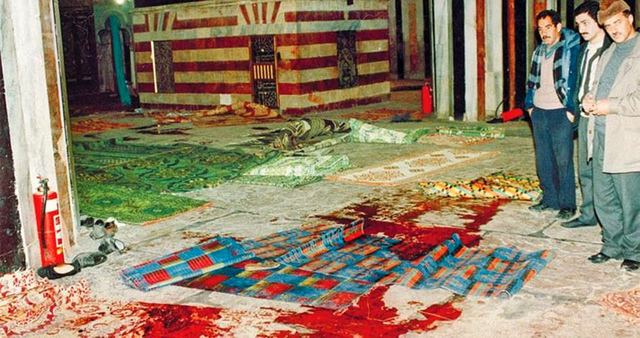

The slow encroachment of settlers into the old city of Hebron and the diminishing of Palestinian rights within the city is an ongoing reality that has been taking place for decades. This process, however, was given a tremendous boost at 5:30 a.m. on the morning of February 25, 1994. That was when Dr. Baruch Kopel Goldstein, an American-born Israeli doctor and a captain in the Israeli army reserves, entered the Ibrahimi mosque in Hebron, known by Jews as The Cave of the Patriarchs. He wore his army uniform including his captain’s rank, and with him he had his Israeli manufactured “Glilon” semi-automatic assault rifle. He carried with him no less than seven magazines, each magazine holding 30 bullets. He entered the prayer hall where an estimated 800 worshipers were praying and began shooting into the defenseless crowd. Dr. Goldstein emptied four magazines before he was heroically taken down and killed by unarmed locals. He murdered 29 Palestinian Muslim worshippers and wounded more than 100. In clashes that took place immediately after the massacre, several dozen more Palestinians were killed and injured by the Israeli forces.

Prayer mats covered in blood at the Ibrahimi mosque in the aftermath of the massacre carried out by Jewish settler Baruch Goldstein, February 25, 1994. (Photo: Al-Khalil)

The Israeli government held that Goldstein was a lone terrorist acting on his own and wanted to distance itself and the state from the massacre. It was decided that an inquiry be appointed by the government to look into the massacre, and a special committee headed by then-Chief Justice Meir Shamgar began its work. The inquiry found that Goldstein acted alone and that there needed to be better security arrangements around the Ibrahimi mosque and throughout the Old City of Hebron. As a result of the massacre, there were several developments in the city that devastated the daily life of Palestinians. One of the decisions made by the minister of police was to create a new police district called “Judea and Samaria.” While this might seem a benign act, it was, in fact, a crucial step in turning what was once The West Bank, a territory temporarily occupied by Israel, into Judea and Samaria, a region permanently within the State of Israel.

The closing of Shuhada Street

Furthermore, by order of the commanding general — an order that is renewed every year or so since 1994 — Shuhada Street, the main business district of the city, was closed down. All the storefronts were locked and bolted and welded shut by the army.

A local shop on Shuhada Street welded shut by the Israeli army. (Photo: Miko Peled)

Vehicles are prohibited from entering the street with two exceptions: Israeli military vehicles and vehicles that are registered in Israel. The only vehicles in Hebron that are registered in Israel are the ones belonging to settlers. Since the second Palestinian uprising in the fall of 2000, street access to pedestrians is also restricted. Checkpoints, movement barriers, cameras, and Jewish-only settlements have been erected throughout the city, severely restricting the local Palestinian’s ability to live a normal daily life.

A neighborhood near the Ibrahimi Mosque in Hebron. The broad side of the street is for Jews and narrow side for Muslims. (Photo: Miko Peled)

Perhaps the best way to understand how devastating this has been for the Palestinian majority of the city, other than by visiting the city, is through an interactive map that shows the choking of Palestinian residents by the army and the settlers in the city. For reference sake, we should note that the Israeli settlers in the city make up no more than 0.4 percent of the entire city population, yet they are able to control 20 percent of the city or the entire Old City of Hebron.

Families must pass through checkpoints to reach their homes. Roads in Hebron are divided in half, one side for Jews, and the other for Muslims. In order to go through a checkpoint, Palestinian residents must be registered. This, Issa Amro explained to me, means that no visitors, repairmen, or ambulances are allowed to cross. For an ambulance to go through, no fewer than five different authorities need to be called and need to respond. First, a call must be made to the Red Crescent, which calls the Red Cross, which calls the Civil Administration, which calls the army commander, who calls the soldier at the checkpoint. If all goes well, the ambulance may drive through. Ambulances are often needed since Palestinians face daily physical attacks by ideologically extreme and violent settlers and soldiers.

When I drive to Hebron to visit the YAS center on Tel-Rumeida, I prefer to do so without going through the hassle of crossing the checkpoints. This requires that I add about 10 km to my trip. Instead of going to the center of the city and then crossing into the Old City, I drive a long loop and arrive at the same spot only from the back side.

A segregated road near the Ibrahimi Mosque. Muslims are only allowed on the narrow side. (Photo: Miko Peled)

Each time I take this trip, and I have taken it dozens of times, I think about the absurdity of the “security” excuse with which Israeli authorities justify the checkpoints and restrictions on Palestinian movement. It could not be an easier trip. Since I drive a car with Israeli license plates I can then return to Jerusalem, driving along the same route, without being stopped, until I am practically back in the city, and then I slow down and wave at the soldiers manning the checkpoint and drive into Jerusalem.

“He is alive, this dog”

One of the most troubling images that have come out of Hebron in recent years was the shooting execution by the Israeli military medic Elor Azariya of a wounded Abd al-Fattah al-Sharif as he lay on the ground. The video begins with 21-year-old Abd al-Fattah laying incapacitated on a Hebron street as ambulances drive around him, and soldiers and civilians with semi-automatic assault rifles walk around him. He is still alive, moving his head from time to time. Around minute 1:16 one of the civilians calls out in Hebrew, “He is alive, this dog.”

Watch | The execution of Abd al-Fattah

At minute 1:45 one of the soldiers who had previously been busy with one of the ambulances walks up to one of the commanders. They talk for a second or two; then the soldier, Azarya, cocks his rifle, walks up to the wounded 21-year-old Abd al-Fattah on the ground and shoots him in the head. There is no commotion, no one stops or reacts other than a few civilians taking pictures. The ambulances drive around what is now the dead body of Abd al-Fattah with blood pouring out of his head. Had this incident not been filmed by a local Palestinian and gone viral no one would have been the wiser.

Because of the video, the army authorities had to react. Resisting a public demand that Azariya be exonerated because he killed a terrorist and that he was only doing his duty, he was eventually charged with and convicted of manslaughter — even though clearly this was premeditated murder. Azarya received an 18-month sentence, which the Israeli Army Chief of Staff, General Gadi Eizenkot, reduced to 14 months. Azariya was home during the trial.

The Campaign to bring awareness, change, and freedom

Israeli soldiers face activists from the Youth Against Settlements group during a demonstration against the closure of al-Shuhada street in Hebron, Sept. 14, 2011. Arabic graffiti on wall reads: "Hajj Shadi Arafat". (AP/Nasser Shiyoukhi)

One could go on and on with stories about Settler violence, vandalism and intimidation towards the local Palestinians, and how the Israeli authorities, namely the army allow and even encourage the settlers violence. Parents are afraid to send their children to school because of settler violence; people are literally caged in their homes with wires and bars on the door and windows because settler vandalism is so prevalent. When altercations between Palestinians and settlers takes place and when the army shows up the burden is on the Palestinians to prove their innocence. It is at the point that Palestinian existence Hebron, and particularly in the old city is nothing short of heroic

Open Shuhada Street Campaign takes place in Hebron and around the world annually during the last week of February to commemorate the massacre at the Ibrahimi Mosque and raise international awareness of the horrifying reality in Hebron. In Hebron itself, the campaign consists of a week of events culminating in a march that attempts to go down Shuhada Street. This year, two activists from Hebron who were supposed to come to the U.K. to speak as part of the Open Shuhada Street Campaign were prevented from doing so. Ahmad Azza, a YAS volunteer, was denied a visa; and journalist Akram Natshe was stopped by Israeli authorities and denied the right to leave.

Baruch Goldstein was a doctor. Elor Azariya was a military-trained medic. Both were Israelis who were sworn to save lives without discrimination, yet both committed heinous crimes, murdering helpless unarmed civilians because they were Palestinian. Some say that Hebron is a microcosm of Palestine, and if this is so, today all Palestinians are like the worshippers at the Ibrahimi mosque and the 21-year-old Abd al-Fattah al-Sharif — being killed and ignored by the world.

Top Photo | Protesters hold posters demanding the reopening of Shuhada Street in Hebron, Friday, Feb. 27, 2015. Israel closed Shuhada Street for Palestinians in 1994 after an Israeli killed 29 Palestinians and wounded over a 100 praying in a mosque. (AP/Nasser Shiyoukhi)

Written by Miko Peled. // This article is Creative Commons. // See the original.

Find us:

Online --> MintPressNews.com

On Twitter --> @MintPressNews

On Facebook --> @MintPressNewsMPN

On Instagram --> @MintPress

On Patreon --> Patreon.com/MintPressNews

Written by Miko Peled. // This article is Creative Commons. // See the original.

Find us:

Online --> MintPressNews.com

On Twitter --> @MintPressNews

On Facebook --> @MintPressNewsMPN

On Instagram --> @MintPress

On Patreon --> Patreon.com/MintPressNews

Breaks my heart to read this, and to think how few people in the states pay any attention

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit