Thursday, 20 July 2017

Welcome to Dispatches, a weekly summary of my writing, listening and reading habits. I'm Andrew McMillen, a freelance journalist and author based in Brisbane, Australia. No new words this week.Sounds:

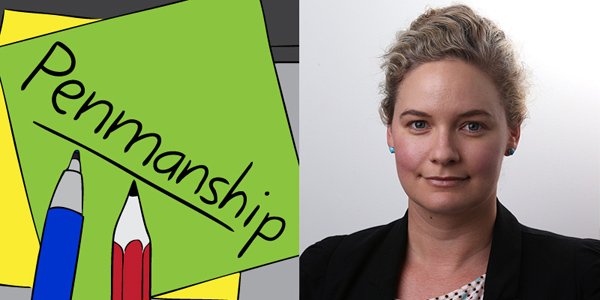

Sarah Elks on Penmanship (91 minutes). Episode 39 of my podcast about Australian writing culture features my conversation with Sarah Elks, Queensland political reporter at The Australian. During her decade of writing for the national newspaper, Sarah has reported on many of the biggest news stories that have taken place in Queensland. It takes tenacity and passion to be a daily news reporter, and Sarah clearly has an abundance of both of these qualities. After extensively covering the fall-out from the closure of the Queensland Nickel refinery in late 2015, Sarah was named Journalist of the Year at the Queensland Clarion Awards for her stories that uncovered Clive Palmer's use of the alias 'Terry Smith' to manage his business while also holding office as a Member of Parliament. The judges for that award in 2016 noted that Sarah's work is "a tremendous how-to for journalists young and old, and deserves recognition".

I met with Sarah at her home in Brisbane's inner-north in early July to record a conversation which touches on how she manages an unpredictable workload that can vary drastically from week to week; how she handled the paranoia of 'correspondent syndrome' while working as The Australian's sole reporter based in Far North Queensland; how her two years in that role took her to a remote island in the Torres Strait, where few people will ever have the privilege of setting foot; why she has a deep and abiding passion for court reporting, which is not shared by many other journalists, and how she increases her likelihood of getting Clive Palmer to respond to her text messages during the course of reporting on the man himself.

Trey Parker on The Nerdist (60 minutes). This is the first time I've heard a long interview with South Park co-creator Trey Parker. Ostensibly conducted to promote his appearance as a voice actor in Despicable Me 3, this is instead a wide-ranging chat about his entire career. I particularly enjoyed about how he never expected to make a career in entertainment, and as a result, he's never taken it very seriously, and is prepared to walk away at a moment's notice... or so he says. I buy it.

Ira Glass on The Turnaround (70 minutes). A new podcast whose premise is simply "interviewers, interviewed"? Yeah, sign me up. I will listen to Ira Glass talk about almost anything, and of course it's a joy to hear him talk at length about how he thinks about editing, storytelling and interviewing. I also liked the episodes with Marc Maron and Susan Orlean, though I think Ira's episode is the best of the bunch to date.Trey Parker (South Park) talks to Chris about working on Despicable Me 3 and what it was like to work on a movie just as an actor. Trey also talks about being a D&D fan, what inspired both their video games and what they are thinking for the next season of South Park!

On the premiere episode of The Turnaround, Jesse talks to Ira Glass, the host and creator of This American Life from WBEZ. This American Life has been on the air since 1995. For more than twenty years, Ira and his fellow producers have helped pioneer a distinctive narrative-driven brand of audio journalism that's become so influential that it's now heard pretty much everywhere. In his conversation with Jesse, Ira explains how he asks questions of people in such a way to draw out a story with a clear beginning, middle, and end. He says he chases after authenticity in his interviews, which sometimes gives way to the kind of emotional moments usually reserved for close friends and relatives.

Reads:

Through The Outback by Adam Ferguson in The New York Times (3,300 words / 16 minutes). This is an extraordinary piece of photojournalism that Adam Ferguson assembled during a three-month trip through central Australia, shooting parts of the country that are rarely seen by other Australians, let alone by the big international audience who saw this stunning work. I believe it was also published as a 16-page colour spread in the newspaper, too, which is just about the biggest platform that any photographer could ask for. It's a thoroughly enjoyable read/view, and once you're done with it, you should check out the Q+A with Ferguson that was published under the title A Photographic Odyssey in the Australian Outback.

The Old Curiosity Shop by Ricky French in The Weekend Australian Magazine (2,000 words / 10 minutes). Saturday's Weekend Australian Magazine was a fantastic issue, and this is the first of three stories from it that I'm recommending today. Here, Ricky French perfectly captures an odd little shop in central Melbourne that time forgot. It's run by a husband-and-wife who are in their 90s, and I love the stage directions and tea-making minutiae that appear throughout the piece.There is a place beyond the mountains of the Great Dividing Range, lost to the shining lights of Australia's suburban sprawl. Known vaguely, if romantically, as the outback, or the bush, it has no demarcated border but refers to the nation's vast, sparsely populated interior – 73 percent of Australia's territory – more than two million square miles – dotted with 5 percent of its 24 million people. It has been mythologized in poetry and song, made horrific in films like "Wake in Fright," and infused into Australia's history and psyche. Yet few Australians, including myself, have fully explored its realities. I grew up in what we call regional Australia – the small cities outside the major capitals – but my mum was from Yeoval, a farming village that was also the childhood home of Banjo Paterson, the Australian poet who romanticized bush life. Until my grandfather died, a slide carousel was a staple of family Christmases: the photographs of Nan, Pop and their five daughters dressed in white English pomp for a country show or the horse races were my own iconic images of this mysterious land.

Anyone With A Heart by Lynn Barber in The Weekend Australian Magazine (3,100 words / 15 minutes). This is a challenging read about a British writer who offers her spare room to a Sudanese refugee for six months, and the tenancy ends in strange, unexpected and unsettling circumstances.You don't notice how out of place 330 King Street, Melbourne, looks because it's rendered so insignificant by its surroundings you don't tend to notice it at all. Built in 1850, it's the oldest residence in the CBD and has been in the same family and run as a shop since 1899. It looks like the neighbouring high-rises are trying to dislodge it and pop it off into the middle of the intersection to be crushed by the number 30 tram. But it digs in. At the front door is a sign: Russells Old Corner Shop, Luncheon Room, NOW OPEN. The tip-off came from a playwright friend. "Get yourself down to those tearooms quick smart. Run by an old theatre couple. You might get a chipped cup but the stories are grand." As meek as it appears now, Russells Old Corner Shop was the heart of the community in the first half of the 20th century, when King Street was all hay and grain stores, grocery warehouses, tea importers, Chinese laundries and family homes. Inside the shop, supplies – honey, cheese, meats, hangover cures – were stacked to the ceiling; at the front counter, lollies dazzled like precious gems. It was in a hollow under this counter that a small girl would crouch, watch and listen, accepting bread and dripping from her grandfather and halfpennies from customers. The making of an actress. Today, that same girl is still in the shop, still watching, listening and welcoming customers through the door. The building is a rare period piece, somehow still standing. The girl is Lola Russell.

Life & Soul by Victoria Laurie in The Weekend Australian Magazine (3,000 words / 15 minutes). A beautiful and extraordinary story about a young organ donor, whose heart still beats in a woman that has now become close to the family of the dead man.This is a story in two parts, without a happy ending, or indeed an ending of any sort. I thought it only fair to warn you. The summer of 2015 brought almost daily horror stories of refugees being drowned at sea or suffocating in semi-trailers while seeking asylum in Europe. The climax was the picture of a dead Syrian boy, Alan Kurdi, washed up on a Turkish beach, though for some reason I was more haunted by a photograph of a Syrian mother trying to hold her baby above the waves. She was my personal tipping point, the moment when I decided I must do something. Not just the usual, comfortable "something must be done" feeling that might induce me to sign a petition or write to my MP, but a much more urgent, anxiety-inducing demand that I, personally, must do what I could to help. But what? I was 71, far from fit, not much use on rescue boats or even soup kitchens. But at least I have a big house. I thought there must be a website where you could sign up to take refugees, but I couldn't find it. I was still puzzling what to do when I happened to meet an artist called Mike Snelle in a London bar. He said he'd been out in the Calais Jungle camp in northern France helping to build shelters for refugees. He said conditions were horrendous, and bound to get worse. I asked what happened to those who did manage to cross the English Channel, and he said they were mostly put in detention centres, unless someone could be found to take them in. I'll take one, I said, and that was that.

Sands Of Time by Jacqueline Maley in Good Weekend (1,200 words / 6 minutes). A wonderfully moving first-person piece about life and death, and learning to navigate between the two as best you can.As a sickly child, Tatiana Neuser-Bostel hated going with her mother to Perth's children's hospital for her frequent heart check-ups. "They'd always call Mum in for a chat for ten minutes before me. That's such a wrong thing to do to a child – I'd think, 'What are they telling her that they're not telling me?'" Tatiana was born with a rare, inoperable heart defect that severely limited the amount of oxygen flowing through her body and led to chest infections and general illness as a kid. Then, as an adult, she started running out of puff as her lungs became as damaged as her feeble heart. When she was 43, a specialist told her she wouldn't make another birthday unless she had a heart transplant. "He put it point blank, 'I can no longer do anything to help you. I will have to pass you on to the advanced heart failure clinic'." She was given 12 months to live. "I said to him, 'Don't worry, I'll invite you to my 50th birthday.' And I did." Tatiana was reborn on the operating table on May 11, 2007, nearly two years after the doctor's dire prediction, when she received the heart and lungs of an anonymous donor. She was the first woman in Western Australia to undergo such an operation. During her recovery, she asked to see photos of the six-hour operation. "I looked and thought, 'Something tells me I have male organs.'

10 Years Ago, I Almost Got Someone Fired While Reporting A Story by Patrick Klepek on Waypoint (1,800 words / 9 minutes). I don't read a lot of videogame journalism, but Patrick Klepek's byline is one that I've known and respected for years, so I was fascinated to read this story about how he failed to protect a source early in his reporting career.Toddlers are not great to take to palliative care wards. They talk too much and get into stuff they shouldn't. They are needy in a more overtly demanding way than the silently ill occupants of the beds of death row. Aunty Helen was reaching the end of her life, so we flew to the Sunshine Coast to be with her. She seemed thrilled, through the constriction of her oxygen mask and the fug of morphine, to see my two-year-old, her great-niece. Her eyes, shrouded with fatigue and fear and something I can only describe as far-awayness, sparked a little. I lifted my daughter's face to rest next to Helen's grey cheek. The invalid tried to talk to the toddler. Helen loved children. She was one of those grown-ups who still had a line to them, and they sensed it. She had a glint in her eye, she was a co-conspirator. Aunty Helen leant into my ear once, when I was about 16, and said drily: "You can drop the 'Aunty', Jac." And I did. After that she became Helen, herself, and I grew beyond the narcissism of adolescence to an age where I could encounter her as a woman in her own right, as opposed to a player in my life.

Night Falls Fast: Understanding Suicide by Kay Redfield Jamison (2000, Vintage). As disclosed on the very first page of this book's prologue, author Kay Redfield Jamison has bipolar disorder, and she describes how she made a "blood oath" with a fellow manic-depressive friend that if one of them again became deeply suicidal, they would meet at his home and spend a week persuading the non-suicidal person not to follow through with their plans. "Who, if not someone who had actually been there, could better bring the other back from the edge?" she writes. "We both, in our own ways and in our own intimate dealings with it, knew suicide well. We thought we knew how we could keep it from being the cause of death on our death certificates."I've been writing and reporting about video games for a long time. It's not only a career, a way to pay the bills and put food on the table, but a passion that drives me out of bed every day, full of curiosity and excitement. The exhilaration felt when breaking the first details on the PlayStation 4 Pro or the fractured breakup of Infinity Ward and Activision is matched only by a desire to enlighten and inform the people who read my work. But none of that's possible without the people who trust me with sensitive information, who take a risk that I won't put their jobs in jeopardy. I've got a pretty clean track record with that. But one time, I fucked up. Why write a story like this? Why open myself to criticism that will, inevitably, be used against me by people with questionable motives? Because mistakes happen, we learn from them, and that's how we get better. It's that simple. This happened back in 2007, when I was working for 1UP, a gaming publication that no longer exists. (It was most notable for pioneering the personality-based games coverage that's become the standard nowadays.) Being the news editor at 1UP was my first "real" job. I'd been writing news articles for 1UP for a few years, in addition to contributing features and reviews to other magazines (EGM, Xbox Nation, etc.), but becoming 1UP's news editor was A Big Deal. Beyond the fact that I was only 22-years-old, having graduated college only a few months prior, I was offered the job after Luke Smith, now creative director on Destiny 2, left for Bungie. Luke made an impact by breaking stories. I wanted to follow in his footsteps.

In this stark, compelling introduction, Jamison skilfully lays out her credentials, and they are mighty hard to argue with. In a sense, Night Falls Fast seems like the kind of book that could only have been written by someone who has experienced the depths of depression and lived to share it with others. Any other author would be viewing this difficult subject from too great a distance, as if describing the features of the moon without ever having set foot on it. "He would call me; I would call him," she writes. "We would outmaneuver the black knight and force him from the board."

The pact didn't hold. Jamison's friends put a gun to his head and killed himself many years later, thereby breaking their other agreement to never buy a gun. Though shaken by his suicide, the author was not surprised: she had been dangerously suicidal on several occasions during the intervening years, yet did not think of calling him. Such is the extreme sense of isolation to which this confounding illness lends itself.

A near-death from a lithium overdose while working in a department of academic psychiatry led Jamison to pursue clinical and scientific research into suicide. "I studied everything I could about my disease and read all I could find about the psychological and biological determinants of suicide," she writes. "As a tiger tamer learns about the minds and moves of his cats, and a pilot about the dynamics of the wind and air, I learned about the illness I had and its possible end point. I learned as best I could, and as much as I could, about the moods of death."

What Jamison attempts here is incredibly difficult, as she is trying to explain something that is practically inexplicable. She acknowledges this on several occasions, in deft passages such as this: "Suicide carries in its aftermath a level of confusion and devastation that is, for the most part, beyond description." Later, she writes: "Everyone has good cause for suicide, or least it seems that way to those who search for it. And most will have yet better grounds to stay alive, thus complicating everything."

Other than the aforementioned prologue, the author keeps herself out of the narrative by exploring the psychology, psychopathology and biology of suicide, while devoting the fourth and final section of the book to prevention. The depth of research and strength of her writing are both remarkable, and it is difficult to imagine a more complete account from a more qualified person. (The narrative itself is about 300 pages long, followed by about 100 pages of exhaustive notes on each chapter.)

"Together, doctors, patients, and their family members can minimize the chances of suicide, but it is a difficult, subtle, and frustrating venture," she writes near the end. "Its value is obvious, but the ways of achieving it are not. Anyone who suggests that coming back from suicidal despair is a straight-forward journey has never taken it." We are grateful that Jamison made her way back from that journey and produced this brilliant piece of work.

++

Thanks for reading. If you have feedback on Dispatches, I'd love to hear from you: just reply to this email. Please feel free to share this far and wide with fellow journalism, music, podcast and book lovers.

Andrew

--

E: [email protected]

W: http://andrewmcmillen.com/

T: @Andrew_McMillen

If you're reading this as a non-subscriber and you'd like to receive Dispatches in your inbox each week, sign up here. To view the archive of past Dispatches dating back to March 2014, head here.