Epigram Books, a Singaporean publisher, is aiming for the Man Booker Prize. As part of its goal, it has opened an imprint in the United Kingdom, so that its offerings will be eligible for the Prize. Founder Edmund Wee believes that the publicity generated from such an achievement "would be a turning point for people to see that Singaporean books aren’t that bad at all".

I wish him the best of luck, but my experience suggests that it's a long shot. I am Singapore's first, and so far only, writer nominated for the Hugo and Dragon Awards. I can tell you that chasing awards means nothing.

Epigram Books is the creator of the Epigram Fiction Prize, Singapore's richest literature award. Each winner receive $25,000 and a publication offer. Per the article:

Out of the 72 entries received in the first year, four were shortlisted and published. All four sold out their initial run of 1,000 copies within two or three months, a milestone that normally takes bestsellers a year to reach in Singapore, according to Wee.

Colour me impressed, but I should note that my own novel, which was not selected for an Epigram Fiction prize, did far better in the same time frame. I'm not sure if I can publicly disclose the actual sales figures, but I can say that neither my publisher nor I had to sink in $25,000 to bring it to the market. We both enjoyed healthy profits from that one book in three months.

And I won't comment on Epigram's UK imprint selling only 100 copies per title in its catalogue.

The key to understanding the TradPub mindset is that they don't sell stories. They sell paper. It's the traditional way of delivering stories to customers. But technology has significantly altered the publishing industry in the past decade.

Print on Demand technology has rendered storing mountains of paper books in bookstores and warehouses obsolete; if you want a paper book, just go on Amazon, and it will print and deliver the book to you. Ebooks are far cheaper than paper books, and far more convenient and accessible in an age of smartphones and tablets. Ereaders and ebook stores have opened the floodgates to new markets and new writers, and search engine algorithms and social media have made discovering and following writers easier than before. Self-publishing platforms allow anybody to write and publish stories from anywhere in the world without having to go through publishers.

Books themselves are facing stiff competition from elsewhere. YouTube, Crunchyroll, Steam, GOG, NetFlix, and other media are all competing with books for the readers' entertainment dollar and time. If a customer has to choose between dropping $18 on a paperback that can be read in 8 hours, or $15 on an indie game that lasts for 50 hours, you can bet that he will choose the latter. Likewise, $18 on a single paperback versus $11.95 on a monthly Crunchyroll premium membership with complete access to all anime and drama in its catalogue is a no-brainer too.

We live in the sunset of traditional publishing. Brick-and-mortar bookstores are closing down, and Big Publishing is declining. Writers and publishers must adapt to changing times or be forgotten.

Encouraging Singaporeans to read Singaporeans may be an admirable goal, but publishers need to remain profitable to continue publishing stories. If they can't make a profit, publishers will be force to close down. Becoming profitable is simple:

Give readers what they want.

Technology may have changed, but readers' tastes have not. Romance readers want love and drama. Thriller readers want excitement and derring-do. SFF readers want awe and wonder. Produce books that meet their expectations, using technology to minimise costs and penetrate markets, and you'll make money.

Publishers need to take a long, hard look at the industry and themselves, and see how they can best serve their readers' needs. Wee's words are instructive of his attitude:

“For many years, it has been in Singaporeans’ minds that foreign books are better and local books not so good,” he says. “I blame everybody. I blame the schools because literature is not compulsory. I blame the bookshops. I blame the press because they still want to interview famous international authors instead of local authors.”

Blaming everybody is not the solution. Courting people with awards will not work. If you don't publish writers whose works people love, people aren't going to love them back. It's as simple as that. Of all the Singaporean-authored books and stories I've read over the years, none of them have left a lingering impression on me. None of them met my tastes -- or my standards of craft.

Chasing a Man Booker Award is a snipe hunt. Writers who can win such an award are incredibly rare. Gambling everything on the hope that that such a talented writer signs on with you is the literary equivalent of putting all your eggs in one basket. After all, what are the odds that a writer capable of winning the Man Booker Award sign on with a small publishing house from tiny country?

Even if Epigram manages such a feat, it's not likely to have a knock-on effect on all other Singaporean books. As I have seen first-hand with the Hugos and Dragons, should an author win an award, readers will flock to the award-winning book, then the rest of his backlist, and only then other authors of similar standards in the same field. Sharing the same nationality as a Man Booker Award-winning writer isn't compelling enough to capture a reader's heart. These other writers must be in the same league as the award winner to stand a chance.

Mickey Spillane once said that people eat more salted peanuts than caviar. Other writers mocked him for his writing style, but through hard work and appealing to the masses, he left his mark on the American crime thriller genre. I have a similar philosophy.

I don't write stories to chase awards. I write stories to entertain my readers. Awards are pleasant, but profits are king. If you want to encourage readers to read more books, you have to sustain the ability to publish more books, and to publish books you need to be profitable. If I were a Singaporean publisher, this is what I would do:

Focus on genre fiction. There is a dearth of genre fiction in Singapore; other than Young Adult and the odd romance and horror story there is a stunning lack of Singaporean genre fiction. Grab the first mover advantage in this field. Don't limit yourself to submissions from Singaporeans, but do try to sign on as many Singaporean genre fiction writers as possible.

Publish stories that meet and exceed genre conventions. Stories must be entertaining. Build a brand focused on quality entertainment and powerful story-telling. In a world where anyone can publish anything, publishers can differentiate themselves by creating a reputation for quality.

Break into ebooks and Print on Demand technology, and target a global audience. The wider your potential market, the more money you make. Minimise cost, maximise distribution.

If your goal is to promote 'literary' works, create another imprint dedicated to literary fiction. Channel profits from genre fiction into this imprint to keep it running. Follow steps 2 and 3, building a reputation for publishing quality work and delivering it to the world. You might not make much money out of the literary imprint, it might even be a loss leader, but hey, you're promoting Singlit and your own brand.

I am leery of 'literary' stories. As far as I'm concerned, there are only two kinds of books: books worth reading, and books not worth reading. To stay competitive, publishers must do the former and avoid the latter. Qualities like 'literariness' or subversiveness or other avant-garde properties take a back seat to market demand. To remain in the publishing game, publishers have to turn a profit. Ignore the market at your peril.

At the end of the day, trad publishers would do well to study the history of publishing. The literati may elevate the heavy, ponderous tomes of great literature -- but it was the cheap pulp magazines, filled with energy and excitement, that instilled the joy of reading in the common people.

--

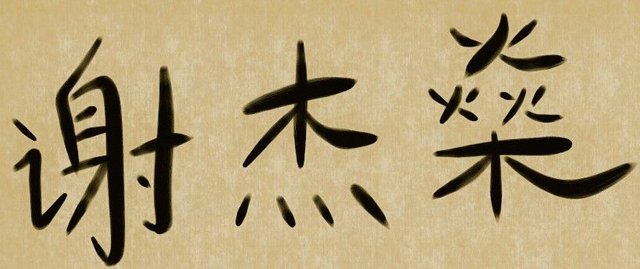

To get a taste of my writing, check out my Steemit serial NIGHT DEMONS and my Dragon Award nominated novel NO GODS, ONLY DAIMONS.

Your post is really good.I like your post.If you like my post,please give me a vote from you.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

I love your writing business posts for their tough-love hard-nosed advice and your perspective as a writer from another country.

Although I have to say I enjoy "literary fiction" to some degree - I want a book that lets me get into a character's head and see the world from a new perspective (consider Lawrence Durrell from last century of George Saunders from this one) - the fact that there are MFA programs around the world selling the dream of "literary fiction" to students by the thousands seems to be one of the greatest scams of higher education. LitFic is all supply and no demand right now.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Thanks. 'Literature' was something I endured in secondary school. To this day, nothing I learned there applied to my writing. That told me everything I needed to know about the applicability of literature to a literary career.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit