You’ve seen versions of the scene a hundred times before. Our Hero is engaged in a gunfight with The Villain. The Villain takes a potshot at Our Hero. Our Hero staggers. When his sidekick catches up with Our Hero and asks after him, Our Hero declares, “It’s only a flesh wound”. In the next scene, Our Hero is patched up and good to go. If the creator even bothers with medical treatment.

In a creative work that treats deadly violence with deadly seriousness, the flesh wound trope is a cop-out. It is a cheap way to increase tension in the scene by showing that Our Hero isn’t invulnerable and that The Villain isn’t incapable, while simultaneously preventing Our Hero from receiving a wound that would prematurely retire him from the story altogether.

To be clear, I’m referring to instances where a character can shrug off an injury as though nothing happened to him, not instances in which a character insists he can keep fighting even though it’s clear he’s gravely wounded. The latter is drama, the former is cheap. Ten seconds on Google would rob anyone of any delusions that a 'flesh wound' isn't serious.

When weapons are involved, there is no such thing as a ‘flesh wound’. It’s like being pregnant: you can’t shoot or stab someone a little bit, and you can’t pretend there won’t be long-term consequences. Once weapons come into play, there are just two questions: how much damage is caused immediately, and how much functionality you recover.

Functionally like this, with more bleeding and screaming.

The human body is amazingly resilient and incredibly fragile. It is resilient in that the major critical organs—the brain, the heart, the lungs—are protected by thick, hard bone, making it difficult to immediately kill someone, and most bodily functions are duplicated, allowing someone to survive the loss of a limb or eye or some other organ. It is fragile in that it is ludicrously easy to shatter bones, sever nerves and destroy muscle if you know what you’re doing—and there is no easy way to undo the damage.

Let’s take the classic example of the bullet to the arm. If the round strikes the forearm, it could break the radius and/or ulna, potentially disabling the arm. If the bullet hits the hand, it would produce an explosion of blood and pain, crippling the hand and potentially severing fingers. A round to the elbow or shoulder will destroy the joint and require reconstructive surgery. And a large enough round will blow off the limb altogether. Even with reconstructive surgery, there is no guarantee the limb will be saved, and there will usually be some degree of permanent loss of function.

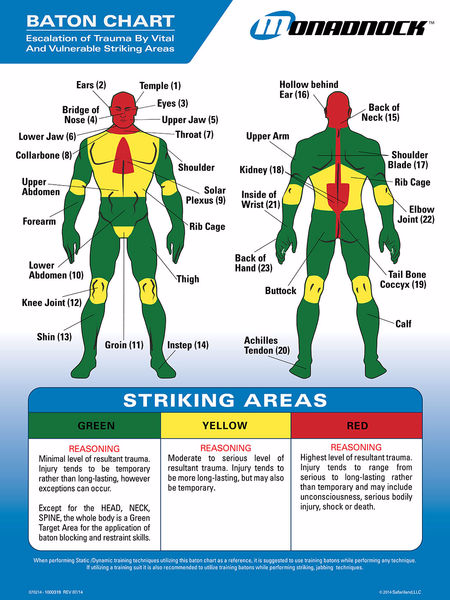

Blunt weapons don’t offer much relief. They are technically less lethal in that the user can choose not to kill someone, but it doesn’t mean it won’t cripple the target either. Many stick striking techniques target the head and the joints. A club or cudgel, used properly, will cause fractures, concussions and traumatic brain injuries. A knockout blow to the head might still kill someone if it strikes with with enough force or if he lands on a hard surface.

The most effective targets are no-go zones for law enforcement...but not for bad guys.

Police officers are specifically trained to target muscle groups instead of bones with their batons—not because these are effective techniques, but to minimise harm to the suspect. This is also why police baton striking techniques create the appearance of police brutality: they are striking the least effective targets on the body, and a subject high on drugs or adrenaline may not feel the pain. When striking with a club, you get to choose between causing pain—not effective against an adrenalized target—or shattering bones—not conducive for allowing Our Hero to continue his adventures. The only time a blunt weapon would inflict the equivalent of ‘flesh wounds’ is by striking muscle, which is not usually in a bad guy’s repertoire.

What about edged weapons? A core concept of Filipino martial arts is defanging the snake, in which the practitioner disarms an aggressor by disabling a limb. When applied to knives, this means targeting the major muscle groups of the arms and legs, leading to an instant stop. Surely, then, this is a flesh wound?

No.

In Martial Blade Concepts, a key technique is the quadriceps cut. The practitioner moves to the target’s side, then stabs the quads and cuts out. There will be little blood and relatively minor nerve damage…and the target will no longer be able to stand unaided.

In Libre Knife Fighting, a tactic is to circle around a target’s weapon side to gain his back, plant the knife next to the spine and cut down. This would sever the major muscles in the back, including the latissimus dorsi. Little blood, minor damage…and the target will no longer be able to lift his arm.

Even if you can inflict an actual flesh wound on someone, if done properly that person will not be able to walk away from it—in some cases, literally. It will take long weeks to recover, if at all. Once weapons are thrown into the mix, the question is not how to ‘safely’ harm the target, but rather how much harm you are willing to do, starting with merely disabling a limb and climbing all the way to death.

And all this is assuming that the story takes place in a setting with modern medicine. In a historical setting or an austere environment with limited access to healthcare, a mere flesh wound would become infected, quickly becoming a horrific pus-filled wound leading to a terrible and painful death. Before the advent of penicillin, anesthesia or even germ theory, there were precious few methods of treating injuries that were not immediately fatal. There was no point trying to save an injured limb if it would inevitably become septic. The preferred method was to amputate the limb to prevent the spread of disease—and even then, prior to the development of sterile surgery people still caught diseases and died. In the American Civil War, one in four patients died from post-surgical illnesses. In such a setting, even if a character survives a non-fatal injury, he is in for a miserable time.

In a creative work where violence is played straight, it would not do for characters to walk off flesh wounds. It flies against the aesthetic of the work, revealing the scene for what it is: a cheap trick to artificially induce tension. And yet a character who routinely prevails in deadly encounters without a scratch appears invincible, inducing audience boredom.

The Art of Safely Injuring Our Hero

For better or for worse, an easy way to increase tension and retain audience interest is to prevent the perception of invulnerability. Our Hero must be seen taking a blow. But he must also survive his injuries without being too damaged to continue his career. There are four ways to do this.

The first method is to take away the weapons. Without weapons, it will be more difficult for people to grievously harm each other. By focusing on body shots, slams, throws, chokes and the occasional head punch, both parties can whale on each other without necessarily causing permanent injuries. Fight-ending shots like throat strikes, eye rakes and joint breaks can be evaded, parried, blocked or countered, prolonging the scene while ratcheting the tension until the time is right to end the fight. Using clever fight choreography, a creator can disguise the fact that neither party is trying to kill or cripple the other while still increasing suspense.

Look past the wire fu and you'll notice that they are not using or landing lethal or crippling techniques.

Chinese martial arts films love this trope. In the above clip from Ip Man 2, Ip Man fights three kung fu masters in succession. Here, Ip Man is fighting to prove his calibre as a teacher and earn the right to run a martial arts school in Hong Kong. Since this conflict is inherently a social one, the combatants will want to avoid lethal techniques, but this implicit rule does not shield Ip Man from failure. The audience may be assured that Ip Man will survive the fight (Ip Man is, after all, a historical character), but not necessarily that he will win, thereby maintaining suspense.

The second method is to use the setting to mitigate the damage. In a fantasy setting, you can have healers with the power to reattach severed limbs and cure terrible wounds. In a science fiction story, a crippled character may rely on prosthetics or cutting-edge medical regeneration technology. Such a setting gives you the best of both worlds: you can still play serious battle wounds straight, leading to loss of blood and limb function, but as soon as the character receives medical care he can be restored to full heath, allowing him to continue the adventure.

During Luke Skywalker’s duel with Darth Vader on Cloud City in The Empire Strikes Back, Darth Vader cuts off Luke’s hand. This demonstrates the disparity in skill between them and allows Darth Vader to reveal that he is Luke’s father. Luke later receives a prosthetic hand, allowing him to participate in Return of the Jedi. In this instant, the science fiction setting makes the prosthetic hand believable, maintaining suspension of disbelief while averting the flesh wound trope.

This would naturally be more difficult to do in a modern setting. Armour is the easiest way to do it, if you can justify its inclusion in the scene. Armour may stop bullets and shrapnel from penetrating flesh, but it would still feel like a hard punch and possibly leave deep bruises. To maintain drama in such a situation, focus on pain, shock, surprise and other psychological effects. In effect, the character knows he’s been hit, but since he took it on the armour, he can keep fighting—even if it hurts like the devil, forcing him to slow down. Wounds to unarmored limbs will still disable the limb, but by applying a tourniquet, the character will still survive – and now he must figure out how to survive despite the loss of a limb. Which is a rich vein to tap for more drama, if you know what you’re doing.

The third method is to play grievous wounds straight but allow a long time for rest and recovery. It’s no coincidence that heroes in realistic thriller series suffer their most debilitating injuries near the end of the story. From the writer’s perspective, since the hero won’t participate in any more combat later in the story, the hero need only survive the scene. By the time of the next story, the hero would have recovered fully—or at least, to the point where he can continue his adventures.

In Barry Eisler’s Winner Take All, John Rain almost bleeds to death. By the time of the next book, Redemption Games, Rain has recovered and is ready for his next contract. By contrast, in Tom Clancy’s Patriot Games, Jack Ryan suffers the classic shoulder wound in the beginning of the story. Ryan spends weeks in hospital, and weeks more in a cast. He also loses some permanent use of his arm. Despite that, by the time of the climax, Ryan is fit for action. This makes sense because Ryan is an analyst: as a desk jockey he doesn’t have to run around and chase bad guys, allowing other characters to participate in action scenes until it’s Ryan’s time to shine.

The last method is the riskiest: inflict the lowest amount of damage possible while justifying it in-universe. This requires extensive knowledge of tactics, techniques, technology and procedures. This method should only be relied on if you do possess such knowledge—or if you know someone who does.

In swordfighting, medium range is the range where both parties can reach each other with their weapons. This is the realm of the double kill. Blade styles that specialise in combat at this range demand mastery of timing, footwork and body mechanics. For instance, when facing a thrust, an exponent may sway back to evade the blade, then launch a riposte along the open line. Such a subtle movement minimises the distance and time the swordsman needs to deliver a counterattack, but it also demands perfection. When dodging an attack, Our Hero may slightly misjudge the distance and receive a shallow wound. Likewise, the villain may evade Our Hero’s slash and launch a sudden riposte; Our Hero shields with his secondary arm and tries to step off, but the offending blade still takes him in the arm. In both cases, Our Hero doesn’t receive a fight-ending injury, or even necessarily a serious one, but the narrowness of his escape emphasises just how close he is to dying and the seriousness of the situation. When played straight, these apparently-shallow wounds will begin to degrade his combat effectiveness, forcing him to take risks. For instance, a seemingly-superficial forehead cut may bleed into the eyes, creating an avenue for reversal and tension, while the arm wound might lead to loss of blood pressure and later consciousness.

With live weapons, a small error in timing and footwork will lead to injury. Notice how narrow the dodges are, and how slim the margin of error.

It is much harder to pull this off in gunfights. In Stephen Hunter’s Point of Impact, a villain shoots Bob Lee Swagger twice in the chest. Swagger survives and escapes. It is revealed that the villain missed Swagger’s heart and had loaded his weapon with hollow point bullets that had failed to expand. The latter is plausible because the story is set in the early 1990s, and hollow points were not a mature technology then. Even so, Swagger is still critically wounded. He struggles with his injuries and requires medical attention (and recovery) before he can continue his investigation. Without knowledge of firearms, ammunition and terminal ballistics, it is very hard to plausibly pull of flesh wounds from a firefight. The old standby, of course, is to have Our Hero grazed by bullets or be struck by fragments from bullets disintegrating against hard cover, but with such minor wounds Our Hero (and therefore the audience) may not even notice them until after the fight.

Flesh wounds are impossible wounds. In a work that plays violence straight, downplaying the effects of injuries contradicts the feel and tone of the work. Instead of going for transparent theatrics, see if you can use the setting to plausibly mitigate the effects of injuries, or play the violence straight and force Our Hero to roll with what he has left. By respecting the consequences of deadly violence, you can maintain dramatic tension while respecting reality and the audience.

--

Image credits:

Baton target: Original image by Monadnock, first retrieved here.

Good job. Interesting for reading. Thank you

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Thanks!

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit