The sense of personal identity is a mirage

The investigation revealed that he was not a doctor as he claimed and, even more difficult to believe, was nothing else. He'd been lying for eighteen years, and that lie didn't cover anything. Near to be discovered, he preferred to suppress those he could not bear to look at. Emmanuel Carrere, The Adversary

Who am I really? The questioning has already occupied us all. Tirelessly, she returns, prelude to the quest for our self that cannot be found. This personal identity, we have difficulty defining it, hidden that it would be under the varnish of our social identity. Indeed, we consider our public face more willingly as incomplete and superficial, like our official identity card, if not exhaustive, in comparison with what we know to be intimately, without the knowledge of others. To put the finger on our personal identity would be to find an authentic, pure, deep self, an original personality, not altered by the behaviour of others towards us.

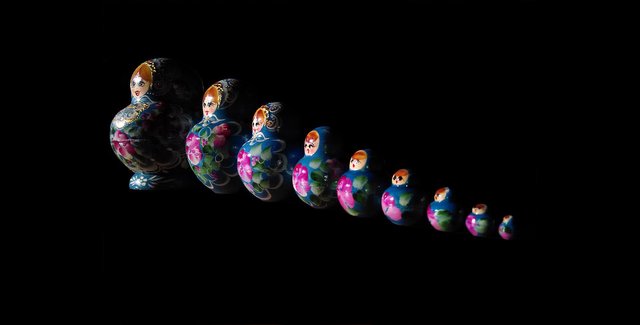

Yet, when we drop the mask, another one comes to light, then another, yet another, indefinitely. Self-knowledge is an illusion, and his quest is vain. Worse still, such research is a hindrance to life. It is an essay that explains it, Far from Me, written by the philosopher Clement Rosset, and published by Éditions de Minuit. It is a short book, but rich in philosophical reflections on the feeling of being, and examples from literature, cinema and life. A book that amuses or disconcerts the reader as he thwarts the most entrenched evidence.

The elusive ego

Clement Rosset studies the feeling that we have of having a personal identity modelled on the famous cogito ergo sum cartésien ("je pense donc je suis"). According to Descartes' scheme, the only doubt-resistant certainty that can be invoked after having ignored any perception is to feel "thinking". The fact of having a reflexive thought on his person would make it possible to affirm the unity of his own self, the inalienable character of his personal identity.

But for Rosset, trying, like Descartes, to find the base of our perceptions to base our identity on, is an absurd project because it is doomed to fail. The Scottish philosopher David Hume questioned the purpose of this exercise in his Treatise on Human Nature:

For my part, when I most intimately penetrate what I call myself, I always stumble upon a particular perception or another, hot or cold, light or shade, love or hatred, pain or pleasure. I can never grasp myself at any time without a perception and I can observe nothing but perception. ...] If someone thinks, after serious and impartial reflection, that he or she has a different knowledge of himself or herself, I have to admit it, I can no longer reason with him or her. ...] Maybe he can perceive something simple and certain that he calls him: and yet I am sure there is no such principle in me."

Our thoughts always encounter particular perceptions, passing feelings. My idea of myself changes along with my perception of my body and mind. What I call myself is therefore floating, indefinite, elusive. Thus, dwelling on one's perceptions in the hope of finding a unified "I" leads to nothing and is always disappointing.

Let's say I see myself on the street. If I came into contact with myself, what would I have to say to myself that I don't already know? What would I have to learn?

Not to be opened

To better understand this illusory character of the self, here is an anecdote reported by Rosset. It is a dealer of labels, signs and other signs of all kinds, who has worked all his life and is dying. His son, who picks up the store, finds a mysterious envelope in which his father's handwritten order to not open can be read.

Displeasing his curiosity, the son respects his father's wishes and leaves the object without piercing his secret. Then, years later, he decided to open the letter in spite of the ban. He thought he was discovering hidden information about his father, a will. But he stumbled upon a number of small signs such as those sold by his father, identical and all bearing the words "Not to open. The envelope contained nothing but signs for the store's customers. The irony is that the son, disappointed, had imagined himself discovering a text to which he gave much more value than a banal formula, repeated a hundred times. Personal identity is struck by the same emptiness: it is a ghostly, phantasmatic object, a hollow concept. An envelope with no content other than itself, and which does not give more information about its state as it is scanned. So finding out who you are has no effect.

I'm another

If the personal identity we think we have in our own is only an illusion, there is a very real identity: social identity.

Non-originality is the common rule of existence

In order to build a personality that does not exist, each one proceeds by imitation of the other. All psychiatrists will tell you, identity is built by copying. A child observes his or her environment, imitates the behaviour of his or her guardians, parents, peers, friends, and there is no reason why he or she should stop copying his or her peers as an adult. This mimetic behaviour is widely observed in the animal kingdom. The borrowed identity is the only true constitutive identity of my self. Moreover, the meaning of the word "identity" - which is identical to, and modelled on - suggests the idea of copying.

This non-originality is the common rule of existence. To define ourselves, we are always dependent on others: we draw our qualities from each other, in the same way that words in the dictionary draw their definition from other words, until successive definitions draw a loop of meaning. You have surely already played with the false paradox that the definition of A refers to B, which refers to C... which refers to A.

It is particularly true of the loving relationship that it is others who give me a full and complete identity. According to a myth reported by Aristophanes in the Banquet of Plato, Zeus, in an outburst of anger, cut in half spherical beings, provided with two sexes, one male and one female. Since then, beings have found themselves in the symbolic form of a half-sphere with only one sex. To recover their totality as much as their identity, they must find their missing part.

Thus, I discover the comfort of my identity with the pleasant feeling of being loved." You love me so I'm here,"says Rosset, parodying Descartes. It is especially noticeable at the first love, very founding. Love is indeed a gift of self, but not as one usually understands it: it is a question of living to the detriment of the other, filling a lack of identity at his expense. This explains the feeling of fullness that lives in us when we are loved.

Cat and mouse play is the best shared experience for couples who thrive." Run away from me I follow you, follow me I run away from you ", the saying goes. In this game, lovers maintain the dreamlike feeling of existing independently of each other. In reality, one person has a personality only to the extent that the other assigns a role to him or her. Rosset explains:

A loves himself by imitating B who loves him; and B in turn loves A, by imitating A who loves himself. The coquette is entirely dependent on the other; but so is the lover. Such cases are common in life and literature, for example in Molière and Marivaux. The conflict proper to coquetry, where A hides in order to perpetuate B's illusory sense of A's autonomous identity, is thus less a conflict of persons than an over-agreement, less the effect of an incompatibility of mood than that of an overly perfect identity of mood."

Similarly, when two friends appear to be made of the same wood and adopt the same reactions, it is that in reality one imitates the temperament and manners of the other. But he didn't invent anything either, and he only developed a personality through mimicry. The fact remains that this duet of friends functions, as for the love relationship, on the mode of dependency, in which one flatters himself to be a model, the other to have a self that he believes to be original. And vice versa.

It is this relationship of dependence that pushes our entourage to sometimes disavow our new way of being, acquired through a recent friendship. That's why it's so difficult to change in the eyes of those who are most frequented and identified with.

Finally, the feeling that it was the other person who gave me my identity appears acutely after the breakup of love: this marks the end of the serenity that I had to be well endowed, to lack nothing, to be me at the expense of the other. The identity crisis that occurs dissolves my well-being, leaves me empty, without knowing who I am, lost.

Self-knowledge cripples existence

If personal identity is a mirage, and if the personality that I have comes from others, it remains to be said that any search for oneself does not help to lead a good life. More than being a goalless project, self-knowledge is an obstacle to existence. Biologically, it has no use: conservation and reproduction, vital functions of the human species like other animals, do not need it.

Can we imagine Roger Federer at work wondering who he is, or what a volley consists of?

Men who accomplish or realize great things in a particular field do not wonder who they are. It is hard to imagine Alexander the Great, at the gates of the Persian Empire, wondering about his identity. To cast doubt on the personality he embodies would also call into question his conquest.

Similarly, in any sport or artistic practice, questions about the nature of my being or my activity hinder the realization of my actions. Can Roger Federer be imagined wondering who he is, or what constitutes a volley when he does it? He would fail, just as the drummer would beat the wrong tempo if he wondered what his role is and how to be a good percussionist. This is also true of an actor, who would lose the sincerity of his interpretation by letting the consciousness take precedence over the feeling.

This is the case for any social situation: spontaneity comes at a time when I am least concerned about knowing myself and assessing whether I am acting according to an alleged personal identity.

Finally, human desire does not obey a single disposition, firmly established by an identical free will according to time and circumstances. On the contrary, it is torn between diverse and often paradoxical tendencies. At the moment when my desire is fulfilled, in a moment of sharing strong emotions, experience proves that there is no need to find out who I am, and on the contrary, it is disabling. The pleasure I have in kissing someone, making love, is never so good that when I leave my questions, my fears, to live these moments in an unthinking way.

Ultimately, fulfilling life is lived in the opposite of a perpetual examination of consciousness. Rather, it is a matter of approaching situations with complete peace of mind about what I am or could be.

If your page is really very successful, will you come back to me

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit