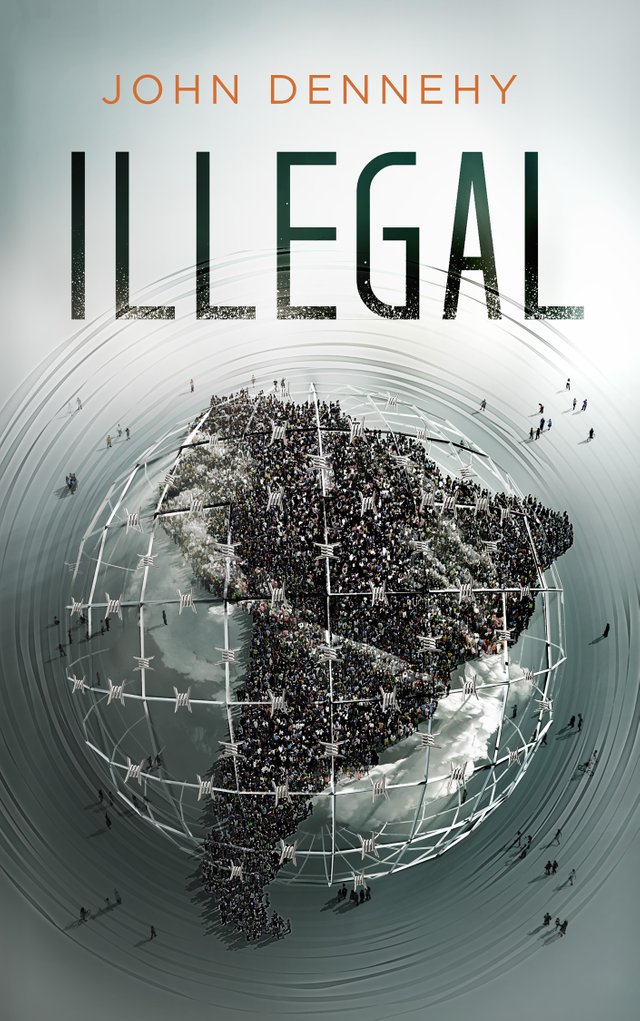

I'm a journalist for publications such as The Guardian, Vice, The Diplomat and Narratively and my first book, a memoir, came out just over a year ago [Amazon link]. It's won numerous awards and sold thousands of copies. And now I want to give it away. This is the twenty-seventh installment [Prologue | Ch 1 | Ch 2 | Ch 3 | Ch 4 | Ch 5 | Ch 6 | Ch 7 | Ch 8 | Ch 9 | Ch 10 | Ch 11 | Ch 12 | Ch 13 | Ch 14 | Ch 15 | Ch 16 | Ch 17 | Ch 18 | Ch 19 | Ch 20 | Ch 21 | Ch 22 | Ch 23 | Ch 24 | Ch 25] and every few days I'll post another chapter. From the back cover:

A raw account of a young American abroad grasping for meaning, this pulsating story of violent protests, illegal border crossings and loss of innocence raises questions about the futility of borders and the irresistible power of nationalism.

--

The Agony of Borders (3) [Chapter Twenty-Six]

I was very tense. This trip seemed less risky than previous ones, but I’d come to learn that what happens at immigration will only be certain when written in past tense. The various branches of immigration in each nation were only consistent in the sense that they consistently gave me different and often contrary instructions; and the crossing at Rumichaca had never been nice to me.

We passed San Gabriel, the last town before Tulcán. The countryside between these two outposts was the most likely place for a checkpoint. I’d been on this stretch of road before, but I remembered it being shorter. I stared out the window into the rain and it seemed we would never arrive. When it rained in this part of the Andes, it was cold and miserable, and no one, not even the police, wanted to stand outside in that unless it was absolutely necessary. I was never so happy to see rain at ten thousand feet.

I readied my story and prepared for interrogation. I decided on a version that, in some ways, mirrored the truth. I would speak Spanish. First show the photocopy and hope it would end there. This was the first part of every plan. If asked for my passport, which was likely, I would calmly hand it over and hope for an unknowing officer who would mindlessly flip through the pages without a second glance.

Everyone assumes that Americans don’t get deported, and I was able to use that to my advantage. There was some sneaking and always the potential for confrontation, but more than anything else, it was a mental exercise. However, there was a very real physical danger involved, and perhaps an even larger perceived one, which was constantly on my mind. Every time I crossed, I risked jail and a forced separation from the dream life that was already slipping out of my control.

At first I only worried about getting caught when I was crossing, but eventually these thoughts and the possible consequences permeated my subconscious and stayed with me every single day. The whole process was incredibly nerve-racking and frightening, but through it all, as I nearly pissed in my pants, I had to keep my head up, walk confidently and smile.

I had my lies carefully prepared . . .

If the officer realized I was illegal, I would claim to have been in Colombia since my deportation, only entering Ecuador a few days ago. I would say that the taxista at the border told me I could skip the long lines at immigration by getting my stamp in Quito. I took his advice and went straight to the capital. While there, I met a friend from high school who does administrative work for the Peace Corps. My friend has a lot of connections with the U.S. Embassy (implying that now I did too, which I hoped would make them hesitate to arrest or deport me) and arranged a meeting with a friend of his. At the embassy I learned I could in fact get my stamp in Quito, but I first needed my exit stamp from Colombia, which I was just now returning to do.

If prompted, I had worked out all the details for my fictitious life, and I was more than ready to play that role. I thought this plan was pretty solid with a minimal chance of failure, but just as every plan begins with silently handing over a photocopy, every plan ends with a bribe.

Thanks largely to the rain and a bit of luck, we made it to Tulcán without ever being stopped. I asked about the bus schedule and got a taxi to the border. I walked across the bridge into Colombia. The rain had subsided and I stood on the bridge, looking down into the deep gorge and the water flowing through it that divided these nations. I let the rush of water drown out all other noise. This place seemed safe. There were no police actually on the bridge, only at its edges. When, for a week in August, both countries refused to accept me and I made dozens of crossings back and forth, this bridge represented an island of tranquility—it was the only place I felt safe, the only place I could exist.

Raising my head and reluctantly moving each foot forward, I let the noise of the world flash back in and entered Colombia. I got my exit stamp and within five minutes I was back on the bridge. Seemingly, my journey was now halfway over. So far everything was going perfectly, but I knew the greatest challenge was still ahead.

My deportation order was for only the calendar year , so theoretically the new year marked a fresh start. Traveling through and then exiting Ecuador was the only part I thought was illegal, but I was still frightened. Months earlier, I’d also had that same impression, that my crossing was legal, just moments before I was arrested and deported. In the months since that setback, reality and paranoia had fused together in my mind. While my deportation order had run out, irrational or not, I was scared. Scared that things might get worse; scared that I couldn’t cope with further setbacks; scared that the whole house of cards would come tumbling down without a moment’s notice. If things didn’t go right at immigration in Ecuador, all my stories and plans would end and I would have to retreat to one of the border towns to contemplate my next step, illegal on either side of the bridge.

I waited anxiously on the long line at Ecuador immigration. If my story was asked, I would use the winner from the bus contest, but it would be more cut and dry here, more of a computer’s choice than a human’s. I thought the machine would be on my side, but I’d been wrong about that before. At the time of my deportation I was told I was banned from entering the country for the calendar year of 2006. Now, three weeks into 2007, one could assume I’d have no trouble getting in, but I had learned to never assume anything at immigration, especially during a nationalist upsurge.

The line for immigration spilled out of the building and into the open mountain air. I took out my notebook and wrote until the rain returned and smeared my ink. Once inside I resumed writing until a friendly Colombian behind me started a conversation. I was grateful for the distraction.

“¿Eres estadounidense?—Are you an American?” he asked.

“Sí.”

“I’ve always wanted to go to your country.”

“It’s good to travel and see new places, but I love it here,” I said.

“Well it’s not as easy for Colombians to travel. You’re lucky, you can just live in my country or Ecuador and you won’t have any problems.”

I forced a smile. It was my turn in line, “Good luck,” I said, and walked to the counter.

The heavyset officer, whose threat of jail had been ringing in my ears for the past year, was nowhere to be seen. Across the counter stood a thinner man who looked tired and bored. I handed over my passport.

He meticulously reviewed it. The tension mounted. He stared at my deportation stamp, and then went through every page, running his fingers over the dozen visas Ecuador had already granted me. He seemed uncertain what to do. My heartbeat raced and my palms sweat, but my face kept a smile. He entered more information into his computer, squinted at the screen, and then, without ever saying a word, gave me my new stamp. At first I hid my joy, but then I realized: I didn’t have to hide anything or wear any mask, at least not at that moment. A huge smile grew across my face as I walked away from the counter.

I quickly got a taxi to the bus station and jumped on a bus as it pulled away from the frontier. On the bus I met a nice Colombian woman living in Ecuador. She was in her late thirties, and had the body of an aerobics instructor, each curve on her body blending into the next. She had a taut face with wide lips, wore tight black pants showing off her well-defined calves, and had flowing, curly black hair that looked fresh from the shower even though it was bone dry. I sat down in the seat across from her and let out a sigh of relief.

“¿Cómo supo usted que podría saltar en el autobús así?—How did you know you could just jump on the bus like that? I’ve never seen a white person do that here. Do you live in Tulcán?” She leaned over inquisitively.

“Well, I’ve been here a lot.” I said, grinning at her. I was feeling confident, so after a short pause I added, “I was fixing my visa at the border.”

“Yeah, I lived in the United States for a few years and had a lot of trouble with immigration there so I know how it must be for you in Ecuador with this new government.” Then she looked at me, the same way that I had looked at her before I told her I had to fix my visa. “I was deported,” she said.

I laughed. “Me too. That’s really why I was at the border, but today for the first time since the deportation, I am legal in Ecuador. What happened to you?”

“I met an American who was doing business in Colombia and we traveled to his country together. We got married there, but we never filed any papers with the embassy and my visa expired so I was illegal. I kept asking him to help me fix my status, but he never did. I don’t think he wanted to. He started to hit me, but I couldn’t call the police because I didn’t want to get deported. So I stopped having sex with him and stayed with friends on the weekends when he was home the most.” Her eyes narrowed and she grit her teeth. “He found a new Colombian to fuck and called the police on me. When they checked my status they tried to deport me, but I fought them.”

“What happened?” I asked.

“I hired the only lawyer I could afford and got them to review my case. I was married to an American and I had a right to stay. They kept me in a jail cell the whole time. We lost the case but I appealed even though I knew I would lose again. I spent eighteen months in jail until they flew me back to Colombia.”

“I’m sorry. But why did you continue to fight if you knew you would lose?” I asked.

“I had done nothing wrong. What was my crime?” She paused before she went on, now looking down, “It just wasn’t right.”

She was a brave woman. We exchanged numbers to keep in touch and wished each other luck.

I rode buses all night and arrived back in Latacunga at 2:00 a.m., nineteen hours after I had left it. It was raining as I walked the deserted downtown streets of the small colonial city to my house. The fairytale life I was living just a few months before was long gone, and yet, soaking wet and walking in the middle of the street the whole way, I felt euphoric. I attributed so many of my problems to my border troubles, and desperately wanted to believe that now things could go back to how they were before.

At our house Lucía was studying and still awake. She jumped up and wrapped her arms around me when I walked in and I thought maybe it would be alright.

If you don't have borders, then you don't have a country.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Borders will always exist. The question is how.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Este trabajo esta super padre, demasiado bueno hermano! FELICIDADES. Muchos saludos desde Venezuela!!

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

gracias

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

hermoso mi amigo, sigue así

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

gracias

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

great job friend.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

great work. Sharing...

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

something to think about

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Right drowning

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

You got a 15.62% upvote from @booster courtesy of @johndennehy!

NEW FEATURE:

You can earn a passive income from our service by delegating your stake in SteemPower to @booster. We'll be sharing 100% Liquid tokens automatically between all our delegators every time a wallet has accumulated 1K STEEM or SBD.

Quick Delegation: 1000| 2500 | 5000 | 10000 | 20000 | 50000

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Hi @johndennehy!

Your post was upvoted by @steem-ua, new Steem dApp, using UserAuthority for algorithmic post curation!

Your UA account score is currently 2.509 which ranks you at #16174 across all Steem accounts.

Your rank has improved 208 places in the last three days (old rank 16382).

In our last Algorithmic Curation Round, consisting of 226 contributions, your post is ranked at #184.

Evaluation of your UA score:

Feel free to join our @steem-ua Discord server

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Congratulations @johndennehy!

Your post was mentioned in the Steemit Hit Parade in the following category:

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

You got a 55.73% upvote from @upmewhale courtesy of @johndennehy!

Earn 100% earning payout by delegating SP to @upmewhale. Visit http://www.upmewhale.com for details!

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Hi

Posted using Partiko Android

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

How about you

Posted using Partiko Android

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

I relate to the anxiety of crossing borders, preparing for potential questions from the authorities, not wanting to set them off, delay me or consider me suspicious. I cringe what the crossing of borders would be like for someone who can't claim as solid as a story - knowing people in government, having the assumed wealth of a foreign traveler.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit