Identifying the thinking process of a particular individual is a lot like detective work. This is especially the case with people who are not physically present or no longer living. Most of what we have to work with is in the form of clues left by those individuals in their writings and in the products or expressions of their thinking. We must work backwards from these clues to deduce the structure of the mental process which produced them.

As a fictitious character, Holmes represents a good example of the purpose of identifying strategies of genius to apply it to contexts other than one in which it was initially developed. Conan Doyle (1859-1930) modeled the methods and mannerisms of the great detective from one of his medical school professors, Dr. Joseph Bell of Edinburgh. Conan Doyle so admired his teacher's abilities to detect and diagnose medical problems that he fantasized about how the processes of this "medical detective" could be applied to actual detective work. The result was Sherlock Holmes.

Sherlock Holmes' popularity and appeal comes from the way he thought. What makes Holmes special is his strategy for approaching a problem - his ability to observe, think and, perhaps most importantly, to be aware enough of his own process such that he can describe and explain it to someone else. Conan Doyle succeeded in being able to robustly capture the thinking process of his teacher and apply it to the interesting and exceptional contexts that made up Holmes' adventures.

In the very first Holmes book, A study in Scarlet, Conan Doyle gives us a hint about the "meta strategy" through which Holmes viewed the problem space in which he worked. Watson discover an article written by Holmes, The Book of Life article suggest that, like all geniuses, Holmes cast his endeavors inside the framework of an ambitious and ceaseless mission to uncover more of the deeper principles expressed in the phenomena of life. Holmes views "life" as an interconnected system, a "great chain, the nature of which is known whenever we are shown a single link of it". Each part of the system carries information about all of the parts of the system, somewhat like a hologram, in which the whole image is pread to each piece of the hologram. Holmes' form of "analysis and deduction" are an expression of the belief that a part of any system is an expression of the whole.

Holmes' claim that a "momentary expression, a twitch of a muscle or a glance of an eye" can give us insight into a person's "innermost thoughts". The implication is that even in seemingly trivial behaviors there are clues to what and how a person is thinking. Holmes claims that this ability is a learnable skill that may be acquired by study but that to someone unfamiliar with these skills it would appear that the person who has developed them would be a magician or "necromancer".

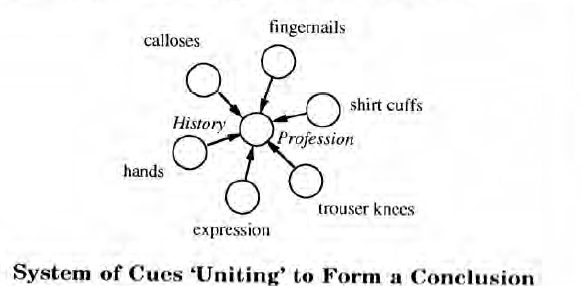

In his article, Holmes gives us a first insight into some key elements of his strategy when he describes his exercise in observation. The macro structure of his strategy involves the process of gathering a number of minor elements together to form a gestalt. By looking at a series of details, such as finger-nails, trouser-knees, callosities of the forefinger and thumb, expression, shirt-cuffs, etc. Holmes is able to infer what they would indicate "all united".

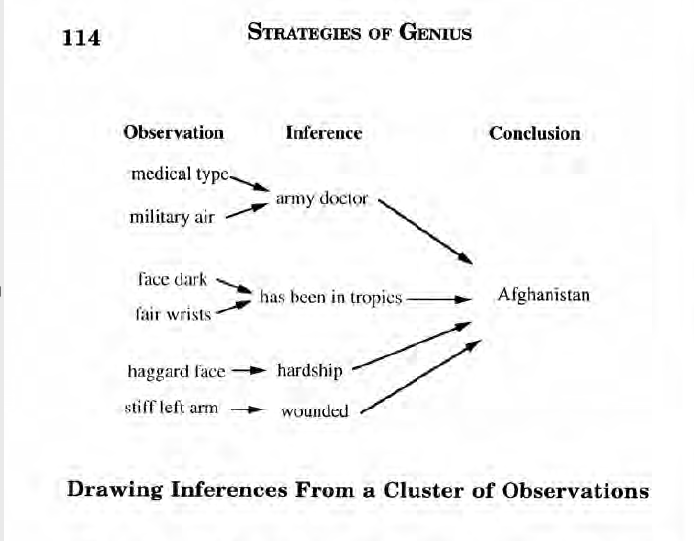

When Holmes explains Watson how he discovered Watson comes from Afghanistan, he gives a more specific description of some of the micro aspects of his strategy and offer us another insight into the nature of his genius - his ability to be aware of and reconstruct the "intermediate steps" of his "train of reasoning".

Holmes' ability to be aware of his own thought process is called meta-cognition; which should be distinguished from "self consciousness". Unlike self consciousness, meta-cognition does not come from a seemingly separate "self" who judges and interferes with the process under observation. Meta-cognition involves only the awareness of the steps of one's thought process. As Holmes demonstrates, meta-cognition will often only reach consciousness after the thought process is completed.

The value of meta-cognition is that by making you aware of how you are thinking, it allows you to constantly validate or correct your inner thinking strategies. In fact, Holmes claimed that his genius was "but systematized common sense."

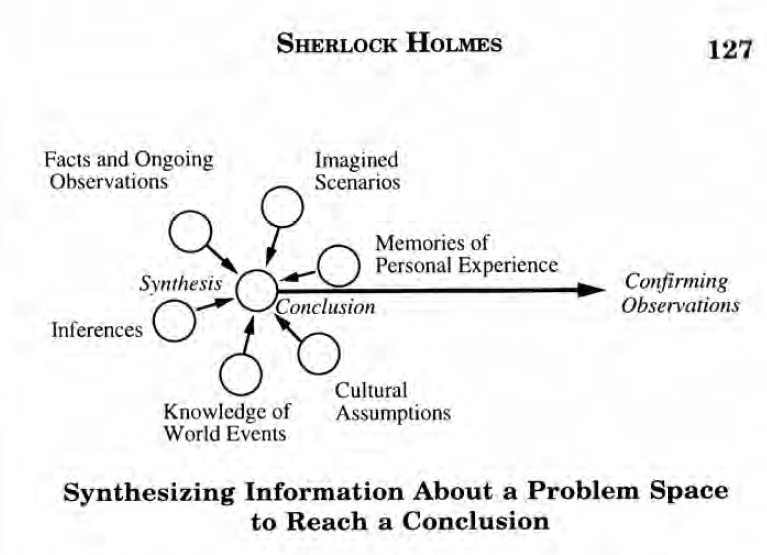

Holmes does not simply observe a bunch of details and draw a conclusion. Rather, he makes inferences from relathionships brought out through combinations of observations. That is, he does not simply look at somebody's skin color and deduce that they have been in the tropics. He looks at the relationship between the tint of his face and the tint of his wrists and infers that it is not the natural skin color, then he makes the conclusion that the person has been in the tropics. The conclusion is not in fact drawn from the observations themselves but from the cluster of inferences arrived at by linking certain observations together. A group of inferences is first drawn from observations of behavioral and environmental details and a conclusion is then drawn from the inferences.

The process of drawning an inference from the perception of a cluster of details is what Holmes considered "observation", not simply the act of perceiving the details. As he said to Watson, "You see but you do not observe".

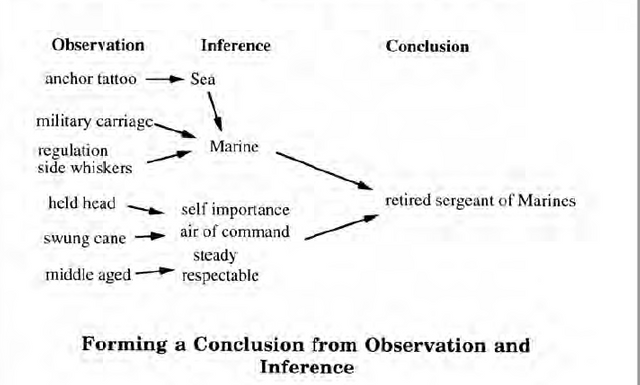

In A Study In Scarlet Holmes demonstrates and describes some of the micro aspects of his strategy again when he correctly deduces the background of a man as a retired sergeat of Marines, who has come to see him as a client and whom he has never before met.

Holmes Micro Strategies for Observation, Inference and Deduction

Clearly, Holmes' ability requires more than simply looking at details As he himself points out, it is more than seeing. He "deduces" his conclusions by relating observations and inferences to one another. To do this, Holmes combines two processes:

- Noticing and giving meaning to externally perceived details and

- Synthesizing a cluster of meanings into a conclusion.

In the Sign of Four, Holmes clearly distinguishes and describes the relationship between his two micro strategies of observation and deduction.

But you spoke just now of observation and deduction. Surely the one to some extent implies the other."

"Why, hardly," he answered, leaning back luxuriously in his armchair and sending up thick blue wreaths from his pipe. "For example, observation shows me that you have been to the Wigmore Street Post-Office this morning, but deduction lets me know that when there you dispatched a telegram."

"Right!" said I. "Right on both points! But I confess that I don't see how you arrived at it. It was a sudden impulse upon my part, and I have mentioned it to no one.

"It is simplicity itself", he remarked, chuckling at my surprise - "so absurdly simple that an explanation is superfluous; and yet it may serve to define the limits of observation and deduction. Observation tells me that you have a little reddish mold adhering to your instep. Just opposite the Wigmore Street Office they have taken up the pavement and thrown up some earth which lies in such a way that it is difficult to avoid treading in it in entering. The earth is of this peculiar reddish tint which is found, as far as I know, nowhere else in the neighbourhood. So much is observation. The rest is deduction."

"How, then did you deduce the telegram?"

"Why, of course, I knew that you had not wirtten a letter, since I sat opposite to you all morning. I see also in your open desk there that you have a sheet of stamps and a thick bundle of postcards. What could you go into the post-office for, then, but to send a wire? Eliminate all other factors, and the one which remains must be the truth."

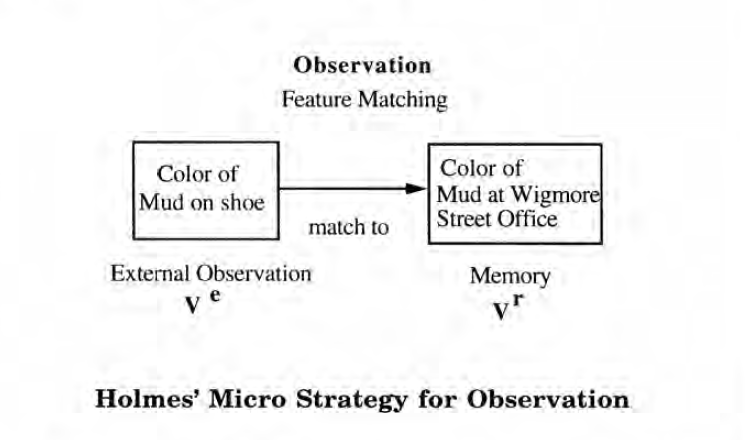

Holmes' micro strategy for observation involves linking a feature, visually input from his ongoing external environment, to inner memories. This is done by matching features of what he is seeing in his external environment to features of remembered situations and events.

Color is the formal feature through which Holmes is able to associate and link his ongoing sensory experience with other experiences in his memory.

To observe, Holmes clearly relies on the visual representational system. Color is one of a number of features of vision that we have previously identified as "submodalities". Each of our sensory representational systems registers objects and events in terms of such features. In addition to color, our sense of sight, for instance, registers size, shape, brightness, location, movements, etc. The auditory representational system senses sounds in terms of features such as volume, tone, tempo and pitch. The kinesthetic system represents feelings in terms of intensity, temperature, pressure, texture and son on.

Unlike the average person, when Holmes is observing he pays more attention to the more formal qualities of what he is observing than to the content of his observation ("incidental objects os sense"). While submodalities could be considered "details" in a way, they are actually not just a smaller piece of an experience but rather a more abstract and formal feature of the object under observation. By extracting key features and using them as his basis for a memory search, Holmes is open to a wider variety of associations than someone who simply sees "mud".

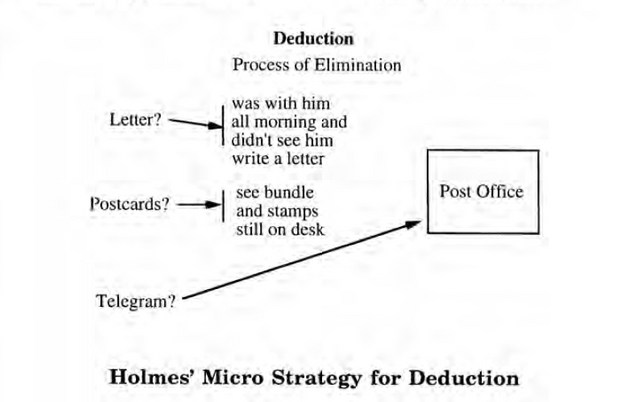

Holmes description of his micro strategy for deduction indicates that it is primarily a "process of elimination". While Holmes' strategy of observation involves connecting a particular perception to other contexts and events through matching features, his strategy for deduction is oriented towards paring down the potential possibilities his observation has suggested in order to reach a single conclusion.

Holmes' process of deduction seems to rely heavily on the visual representational system. He uses visual memories or external observations that appear to be prompted or connected by verbal statements or questions.

Holmes' Macro Strategy for Finding "Antecedent Causes"

It would appear that Holmes had a very highly developed strategy for finding what Aristotle called "antecedent" or "precipitating" causes - past events, actions or decisions that influence the present state of a thing or event through a linear chain of "action and reaction".

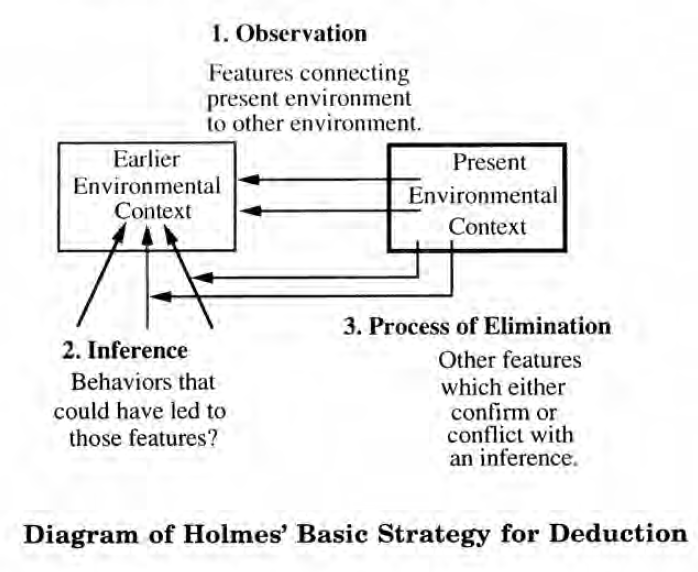

The essential steps in Holmes' macro strategy for identifying antecedent causes seem to be:

- Observation to determine the effect of events on the environmental context.

- Use inference to determine the possible behaviors that could have led to those environmental effects.

- Use deduction to reduce the possible paths of behavior to a single probability.

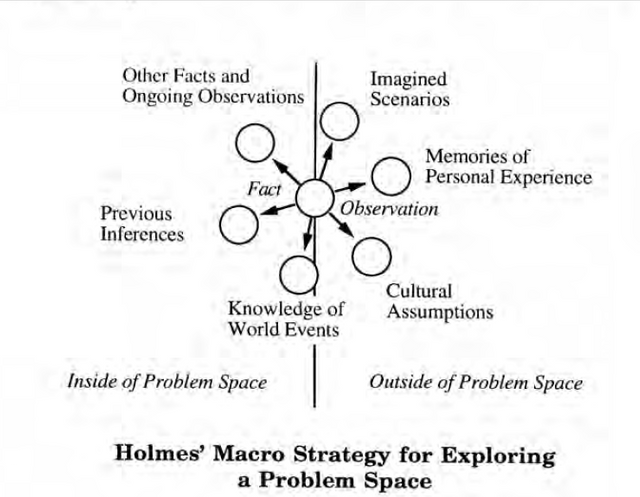

There is one very important part of Holmes strategy, however, that he never mentions - how the determines what could be called the problem space within which to work.

In order to draw an inference about a previous state, you must make assumptions about the problem space in which you are operating. One's definition of and assumptions about a problem space will influence and will be influenced by a number of key elements of problem solving:

1. Interpretation of the meaning of an input or event. Connecting a particular input or event into other frameworks. For instance, in order for Holmes to conclude that Watson had been in Afghanistan after he had inferred that Watson was an army doctor with a tan and a wound, he had to have some knowledge of contemporary world events - in particular, recent British military campaigns. Holmes would not have drawn the same conclusion in today's world if he met a tan and wounded British Doctor.

As Holmes himself pointed out,

"Circumstantial evidence is a very tricky thing. It may seem to point very straight to one thing, but if you shift your own point of view a little, you may find it pointing in an equally uncompromising manner to something entirely different."

2. Completeness / thoroughness of coverage of the problem space. Since everyone must make assumptions in order to give something meaning, we might ask, "How does one minimize problems brought about by inappropiate assumptions or mistaken interpretations?" One answer relates to how thoroughly one covers the total possible problem space. Perspective is one key element of problem space. Time frames are another. Perhaps one reason that Holmes outperforms his peers and competitors is that he is simply more complete in his coverage of the possible perspectives and time frames that could be part of a particular problem.

3. Order in which problem features / elements are attended to. The sequence in which one makes observations and inferences can also influence the conclusion one draws - especially when inferences are being drawn from one another. Some inferences are not possible to make unless others have already been made. Sequence is implicit in the concept of a "strategy". We have already identified a macro level sequence to Holmes process involving first observation, followed by inference and then finally deduction. On a more micro level, Holmes appears to initially pay attention to clues that would give him contextual information and then detail the actions or events that have taken place within that context.

4. Priority given to problem elements / features. While Holmes appreciate the importance of "minutiae" he does not value all of them equally. In addition to sequence, the priority or emphasis given to various clues or elements determines their influence in shaping and inference or conclusion.

5. Additional knowledge about the problem from sources outside the problem space. Holmes used not only knowledge about cultural patterns and world events but also relatively obscure and sometimes esoteric knowledge to make inferences and draw conclusions.

6. Degree of Involvement of Fantasy and Imagination. Another source of knowledge that originates outside of a particular problem space is imagination. Holmes often utilized his imagination to make inferences, claiming that his methods were based on a "mixture of imagination and reality". Holmes' use of his imagination seems to be a complementary process to deduction. While problem solving based on deduction employs observations to eliminate possible pathways, problem solving based on imagination employs observations to confirm a supposed scenario.

In general, Holmes' macro strategy is to connect particular observations to a number of frameworks both inside and outside of the scope of the problem space he is addressing.

Holmes then synthesizes this information together into a single conclusion which is confirmed by other observations or a group of suppositions that is reduced to a single possibility through a process of elimination. Holmes emphasized the importance of this last step when he pointed out that so often

"Insensibly one begins to twist facts to suit theories, instead of theories to suit facts."

A good example of this strategy comes from the Sign of Four in which Holmes is able to draw a number of conclusions about Watson's brother from examining his watch.

“I have heard you say that it is difficult for a man to have any object in daily use without leaving the impress of his individuality upon it in such a way that a trained observer might read it. Now, I have here a watch which has recently come into my possession. Would you have the kindness to let me have an opinion upon the character or habits of the late owner?”

I handed him over the watch with some slight feeling of amusement in my heart, for the test was, as I thought, an impossible one, and I intended it as a lesson against the somewhat dogmatic tone which he occasionally assumed. He balanced the watch in his hand, gazed hard at the dial, opened the back, and examined the works, first with his naked eyes and then with a powerful convex lens. I could hardly keep from smiling at his crestfallen face when he finally snapped the case to and handed it back.

“There are hardly any data,” he remarked. “The watch has been recently cleaned, which robs me of my most suggestive facts.”

“You are right,” I answered. “It was cleaned before being sent to me.” In my heart I accused my companion of putting forward a most lame and impotent excuse to cover his failure. What data could he expect from an uncleaned watch?

“Though unsatisfactory, my research has not been entirely barren,” he observed, staring up at the ceiling with dreamy, lack-lustre eyes. “Subject to your correction, I should judge that the watch belonged to your elder brother, who inherited it from your father.”

“That you gather, no doubt, from the H. W. upon the back?”

“Quite so. The W. suggests your own name. The date of the watch is nearly fifty years back, and the initials are as old as the watch: so it was made for the last generation. Jewelry usually descents to the eldest son, and he is most likely to have the same name as the father. Your father has, if I remember right, been dead many years. It has, therefore, been in the hands of your eldest brother.”

“Right, so far,” said I. “Anything else?”

“He was a man of untidy habits,—very untidy and careless. He was left with good prospects, but he threw away his chances, lived for some time in poverty with occasional short intervals of prosperity, and finally, taking to drink, he died. That is all I can gather.”

I sprang from my chair and limped impatiently about the room with considerable bitterness in my heart.

“This is unworthy of you, Holmes,” I said. “I could not have believed that you would have descended to this. You have made inquires into the history of my unhappy brother, and you now pretend to deduce this knowledge in some fanciful way. You cannot expect me to believe that you have read all this from his old watch! It is unkind, and, to speak plainly, has a touch of charlatanism in it.”

“My dear doctor,” said he, kindly, “pray accept my apologies. Viewing the matter as an abstract problem, I had forgotten how personal and painful a thing it might be to you. I assure you, however, that I never even knew that you had a brother until you handed me the watch."

“Then how in the name of all that is wonderful did you get these facts? They are absolutely correct in every particular.”

“Ah, that is good luck. I could only say what was the balance of probability. I did not at all expect to be so accurate.“

“But it was not mere guess-work?”

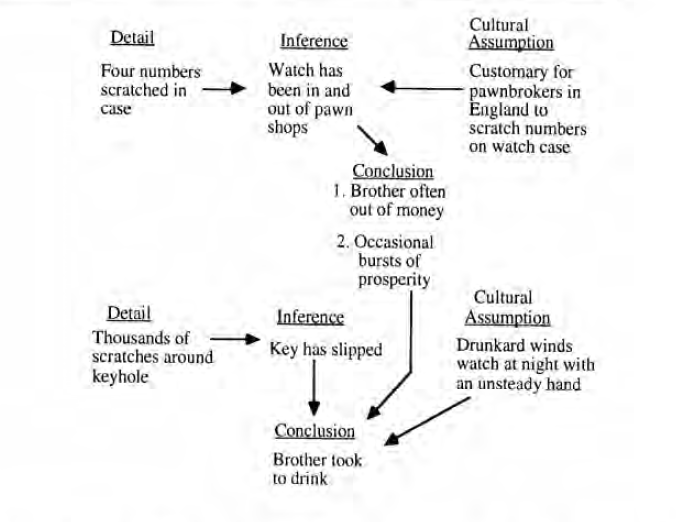

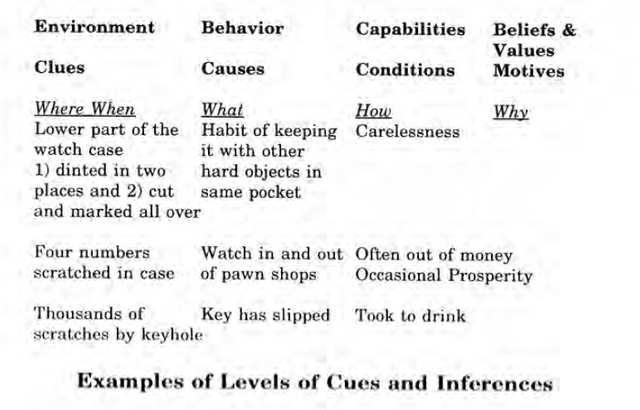

“No, no: I never guess. It is a shocking habit,—destructive to the logical faculty. What seems strange to you is only so because you do not follow my train of thought or observe the small facts upon which large inferences may depend. For example, I began by stating that your brother was careless. When you observe the lower part of that watch-case you notice that it is not only dinted in two places, but it is cut and marked all over from the habit of keeping other hard objects, such as coins or keys, in the same pocket. Surely it is no great feat to assume that a man who treats a fiftyguinea watch so cavalierly must be a careless man. Neither is it a very far-fetched inference that a man who inherits one article of such value is pretty well provided for in other respects.”

I nodded, to show that I followed his reasoning.

“It is very customary for pawnbrokers in England, when they take a watch, to scratch the number of the ticket with a pin-point upon the inside of the case. It is more handy than a label, as there is no risk of the number being lost or transposed. There are no less than four such numbers visible to my lens on the inside of this case. Inference,—that your brother was often at low water. Secondary inference,—that he had occasional bursts of prosperity, or he could not have redeemed the pledge. Finally, I ask you to look at the inner plate, which contains the key-hole. Look at the thousands of scratches all round the hole,—marks where the key has slipped. What sober man’s key could have scored those grooves? But you will never see a drunkard’s watch without them. He winds it at night, and he leaves these traces of his unsteady hand. Where is the mystery in all this?”

In this example, Holmes demonstrates how he synthesizes associations from a number of different frameworks to build a characterization of Watson's unfortunate brother. Holmes pieces together contextual information with cultural assumptions and his own personal memories to provide a rich space in which to give meaning to the semingly trivial details he has observed on the watch.

Levels of Cues and Inferences

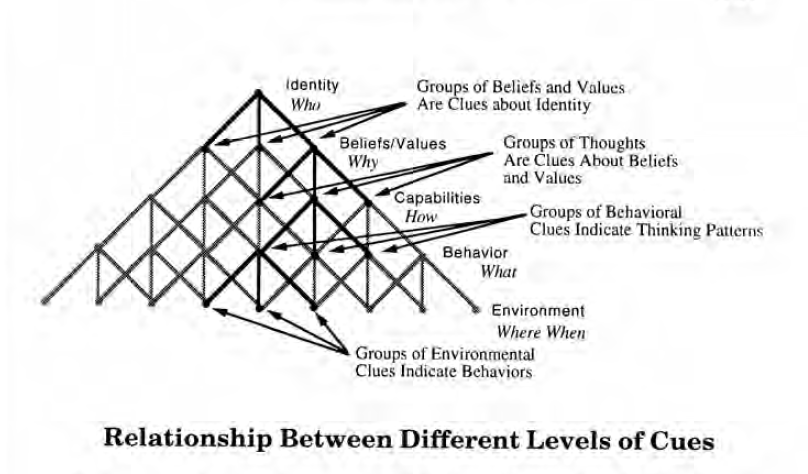

Holmes seems to have been a master at tracing and applying the interconnections between these levels. Clusters of clues left in the environment tell us about the behaviors that have caused them. Clusters of behaviors are clues about the cognitive processes and capabilities that produce and guide those behaviors. Cognitive strategies and maps are clues about the beliefs and values that shape and motivate them. Clusters of beliefs and values provide clues to the identity and personality at their core.

For example, in the case of Watson's watch, Holmes puts together cluster of minute environmental clues left on the watch together with contextual and cultural assumptions to infer what behaviors caused these clues. He then synthesizes these behavioral causes together with some other cultural assumptions to converge on a conclusion about the deeper conditions that brought about those behaviors.

Holmes was not a psychologist. As a detective he had to focus on the concrete behavioral aspects of his cases. Most of the examples we are given in the Holmes stories are about discovering the behaviors that have left their traces in the environment rather than uncovering cognitive strategies. Yet, Holmes did also claim that a "momentary expression, a twitch of a muscle or a glance of an eye" can give us insight into a person's "innermost thoughts."

In The Adventure of the Cardboard Box, Holmes provides a powerful example of applying his methods to uncover a "train of thought" in Watson. Instead of inferring behavioral actions ("antecedent causes") from environmental clues, he infers cognitive processes ("final causes") from clusters of behavioral clues.

Finding that Holmes was too absorbed for conversation I had tossed side the barren paper, and leaning back in my chair I fell into a brown study. Suddenly my companion’s voice broke in upon my thoughts:

“You are right, Watson,” said he. “It does seem a most preposterous way of settling a dispute.”

“Most preposterous!” I exclaimed, and then suddenly realizing how he had echoed the inmost thought of my soul, I sat up in my chair and stared at him in blank amazement.

“What is this, Holmes?” I cried. “This is beyond anything which I could have imagined.”

He laughed heartily at my perplexity. “You remember,” said he, “that some little time ago when I read you the passage in one of Poe’s sketches in which a close reasoner follows the unspoken thoughts of his companion, you were inclined to treat the matter as a mere tour-de-force of the author. On my remarking that I was constantly in the habit of doing the same thing you expressed incredulity.”

“Oh, no!”

“Perhaps not with your tongue, my dear Watson, but certainly with your eyebrows. So when I saw you throw down your paper and enter upon a train of thought, I was very happy to have the opportunity of reading it off, and eventually of breaking into it, as a proof that I had been in rapport with you.”

But I was still far from satisfied. “In the example which you read to me,” said I, “the reasoner drew his conclusions from the actions of the man whom he observed. If I remember right, he stumbled over a heap of stones, looked up at the stars, and so on. But I have been seated quietly in my chair, and what clues can I have given you?”

“You do yourself an injustice. The features are given to man as the means by which he shall express his emotions, and yours are faithful servants.”

“Do you mean to say that you read my train of thoughts from my features?”

“Your features and especially your eyes. Perhaps you cannot yourself recall how your reverie commenced?”

“No, I cannot.”

“Then I will tell you. After throwing down your paper, which was the action which drew my attention to you, you sat for half a minute with a vacant expression. Then your eyes fixed themselves upon your newly framed picture of General Gordon, and I saw by the alteration in your face that a train of thought had been started. But it did not lead very far. Your eyes flashed across to the unframed portrait of Henry Ward Beecher which stands upon the top of your books. Then you glanced up at the wall, and of course your meaning was obvious. You were thinking that if the portrait were framed it would just cover that bare space and correspond with Gordon’s picture there.”

“You have followed me wonderfully!” I exclaimed.

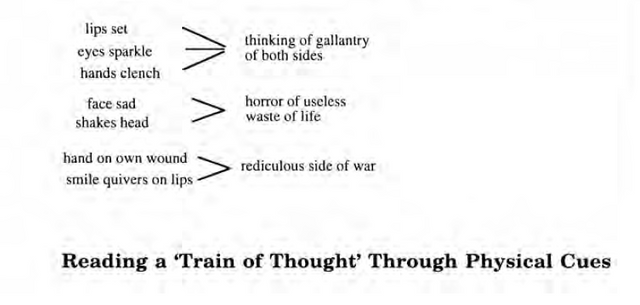

“So far I could hardly have gone astray. But now your thoughts went back to Beecher, and you looked hard across as if you were studying the character in his features. Then your eyes ceased to pucker, but you continued to look across, and your face was thoughtful. You were recalling the incidents of Beecher’s career. I was well aware that you could not do this without thinking of the mission which he undertook on behalf of the North at the time of the Civil War, for I remember your expressing your passionate indignation at the way in which he was received by the more turbulent of our people. You felt so strongly about it that I knew you could not think of Beecher without thinking of that also. When a moment later I saw your eyes wander away from the picture, I suspected that your mind had now turned to the Civil War, and when I observed that your lips set, your eyes sparkled, and your hands clenched I was positive that you were indeed thinking of the gallantry which was shown by both sides in that desperate struggle. But then, again, your face grew sadder, you shook your head. You were dwelling upon the sadness and horror and useless waste of life. Your hand stole towards your own old wound and a smile quivered on your lips, which showed me that the ridiculous side of this method of settling international questions had forced itself upon your mind. At this point I agreed with you that it was preposterous and was glad to find that all my deductions had been correct.”

Implementing Holmes' Strategy

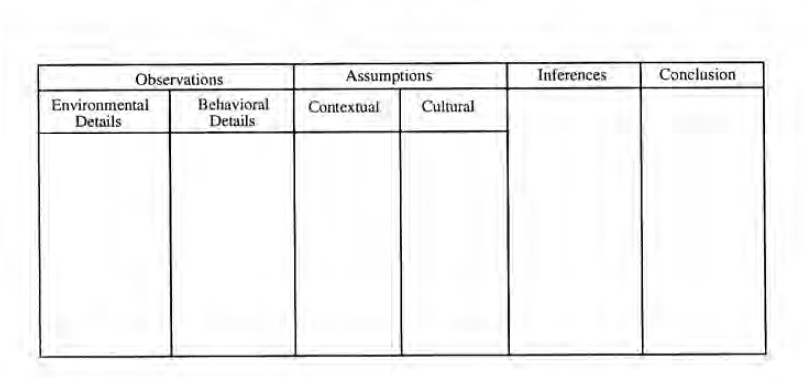

Let's see how we might develop and implement some of the skills and strategies of Sherlock Holmes in the context of our own lives. Holmes' strategy basically involves the synthesizing of a cluster of environmental and behavioral clues to form a conclusion out of the whole. This process involves a number of key elements and sub-skills including:

Observation - Matching the features of environmental clues left in one context to characteristics of other contexts.

Assumption- Presupposed knowledge or beliefs about the larger framework or "problem space" in which some clue is occurring. Assumptions determining the meaning or significance of a clue.

Inference - Imagining what kinds of actions could have produced the environmental clues you are examining inside of the problem space you are assuming.

Deduction - Eliminating or confirming possible actions by finding other confirming or disconfirming clues for each possibility.

Meta Cognition - Being introspectively aware of your own thought process, and keeping track of the "trains of thought" that lead to your conclusions.

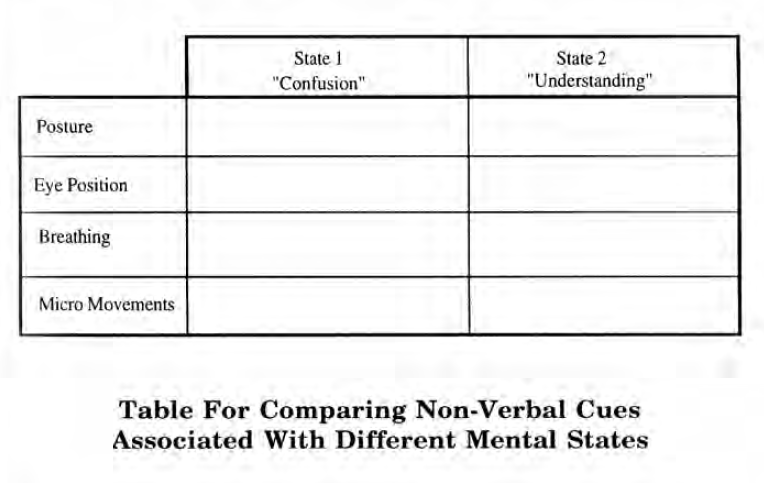

Calibration Exercise

One way to use a "momentary expression, a twitch of a muscle or a glance of an eye" to gain insight into a person's "innermost thoughts" is by calibration. It involves linking behavioral cues to internal cognitive and emotional responses. Find a partner and try the following exercise together:

Ask your partner to think of some concept that your partner feels she or he knows and understands.

Observe your partner's physiology closely as if you were Sherlock Holmes for a moment. Watch your partner's eye movements, facial expressions, breathing rate, etc.

Then ask your partner to think of something that is confusing and unclear.

Once again, watch your partner's eyes and features carefully. Notice what is different between the patterns of features.

Now ask your partner to pick either concept and think of it again. Observe your partner's features. You should see traces of one of the clusters of features associated with either understanding or confusion.

Make a guess and then check with your partner to find out if you were correct.

Have your partner think of other concepts that she or he understands or finds confusing and see if you can guess which category they fall into. Confirm your guess by checking with your partner.

As a test of your skill, explain some concept to your partner and determine whether your partner has understood it or is unclear or confused by observing his or her features.

Detecting Deceit

According to Holmes deceit was "an impossibility in the case of one trained in observation and analysis". The following exercise combines observational skill with analytical skill and a little imagination. Try it with a partner:

Ask your partner to hide a coin in either hand and purposely try to fool you as to which hand it is in.

You get to ask five questions of your partner in order to try to determine which hand the coin is in. Your partner must answer all of the questions, but does not have to answer truthfully.

After your five questions you must make a guess as to which hand you think the coin is in. Your partner will then open both hands and show you the answer.

The best way to see through your partner's ruse as if you were a human "lie detector" is by observing for subtle unconscious cues associated with "yes" and "no" responses. It is generally a good idea to set up your calibration before your partner realizes that is what you are doing.

Pay particular attention to cues that your partner will probably not be aware of or cannot consciously manipulate. For instance, if you are an acute observer you might see very subtle responses like skin color changes, pupil dilation, or slight breathing shifts, etc. Once helpful principle to apply is what I call the "1/2 second rule" which is that any response that comes within a half second of your question has probably not been mediated by your partner's conscious awareness.

Keep in mind that people will be able to infer what you are going to ask before you even complete your question so you can start observing his or her reactions even before you have finished your sentence.

Like Holmes, you can make of use cultural assumptions such as asking, "Is the coin in the hand you hold your fork with?" You may also make use of any memories you can recall, such as "Is the coin in the hand you opened the door with?" or "Are you holding the coin in the hand that I was holding it in when I gave it to you?" Since your partner will have to direct some of his or her attention to thinking of the experiences you are referring to, it will extend your chances of getting an initial unconscious response that has not been filtered by conscious attention. You might also try asking Meta Questions - questions about the response the person has given you. For instance, after your partner has answered you, ask, "Did you just tell me the truth?" or "Should I believe what you just answered?" Similarly, don't just observe your partner's initial non verbal response to your question, watch your partner's reaction to his or her own answer.

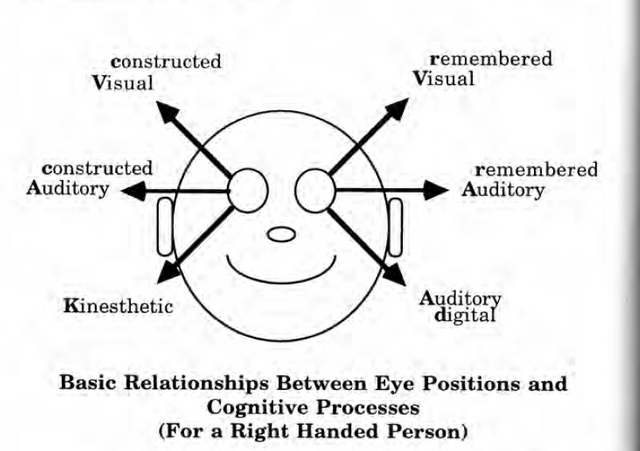

Observing Micro Behavioral Cues Associated with Cognitive Strategies: The B.A.G.E.L. Model

Another application of Holmes' strategies involves combining them with what is known as the B.A.G.E.L. model in NLP. Holmes commented to Watson that a person can "read" your "train of thoughts" from your physical features "and especially your eyes." The B.A.G.E.L. model identifies a number of types of behavioral cues, involving one's physical features and one's eyes, that are associated with cognitive processes - in particular, those involving the five senses. B.A.G.E.L. stands for:

B - Body posture. People visualizing tend to be in an erect posture. When listening tend to lean back a bit with their head tilted. When having feelings tend to lean forward and breath more deeply.

A - Auditory cues, non verbal cues. Voice tone and tempo.

G - Gestures.

E - Eye movements.

L - Language patterns. For example somebody might say "I just feel that something is wrong", this statement indicates a different sensory modality (kinesthetic) than somebody who says, "I'm getting a lot of static about this idea" (auditory), "Something tells me to be careful" (verbal) or "It's very clear to me" (visual). Each statement indicates the cognitive involvement of a different sensory modality.

Hello @jvaldivia,

You have received upvote from @steempeninsula account.

keep writing good content.

Follow @steempeninsula and you may contact on us on [Discord] for any enquiry.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Hello @steempeninsula,

Thanks so much for your upvote, I hope to be able to live out of this, :) I'm following you mate!

Much appreciation!

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit