A particular political regime is the outcome of violence, but also of exchange. If a contractarian political regime can exist, it will include exchanges of liberties for securities. I will agree not to exercise my capacity to violence, or to exchanges that generate negative externalities, if you will also agree to do the same.

We can imagine a constitutional moment in which we discuss which rules we can all agree to to minimise the imposition of negative externalities on one another. No one particular set of rules is best. Rather, every set of rules imposes some costs on some individuals and some benefits on others. If a consensus regarding the rules can be achieved then we can have a pluralistic political regime. Of course, such exchanges are corrupted by the exercise of violent capacities.

Similarly, in markets patterns of exchange emerge that benefit the participants over time. However, in some cases, a mutually beneficial exchange may generate a negative externality onto some individuals not involved in the exchange. If such negative externalities persist, if the political process cannot discover ways to return the cost of those externalities onto the parties engaged in those exchanges, then privilege will develop.

Competition and entrepreneurship can serve to discipline the activities of serial externality-generators. But not always. Sometimes those problems need to be addressed through the political process, through the exchange of liberties and securities, in democratic deliberation.

So, both market exchange and political exchange develop "spontaneously" among groups of individuals. Each particular individual's actions are not spontaneous, but purposeful. Violence in markets, just as violence in politics, will result in unjust outcomes.

Attempts to intentionally engage in social systems of power for the common good, like attempts to capture profits in the market, need to be disciplined by a competitive process.

In democratic institutions, that requires an arena for deliberation where every voice carries equal weight. Where everyone affected by a change in a policy, a rule, or a process has equal opportunity to express their consent. In such an arena everyone has an opportunity to offer compromises, exchanges, such that a consensus can emerge.

There can be no presumed ethical framework going into such a conversation. Rather, just as prices are discovered through the competitive process, the set of rules we can come to consensus about are discovered through a robust and egalitarian deliberative process.

The appropriate role of the political economist in such conversations is not to impose a set of rules that embodies a particular ethical perspective. Not to propose this policy or that policy as "best" while assuming some agreed-upon or imposed perspective on what "best" means or what people should want.

Rather, the appropriate role of the political economist is such conversations is to demonstrate the opportunity costs of alternative sets of rules such that those engaged in the deliberation are well-informed when coming to consensus over the particular regime that will be adopted.

This de-thrones the economist as elite policy-maker and submits his analysis to the approval or disapproval of the polity.

Sounds interesting but not easy to grasp especially for someone who isn't within this said field. Maybe more practical examples will help drive your point.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

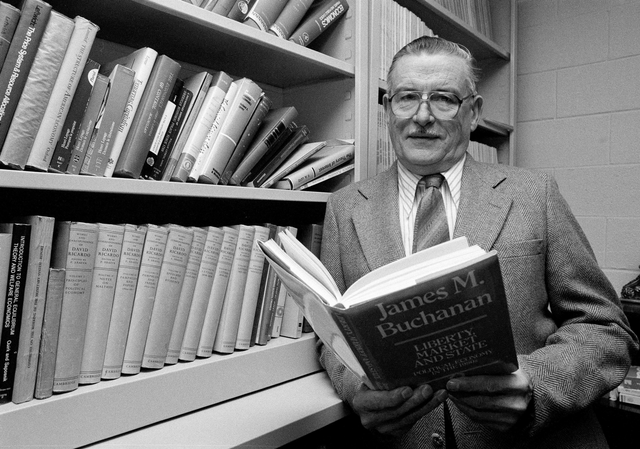

I think the last time I heard about Buchanan was in high school, maybe because I lost interest in economics. Now I'm seeing it again after many years.

Thanks for sharing and for bringing back old memories :)

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit