Precursor to the Mỹ Lai Massacre: 1968 Phong Nhị, Phong Nhất_25: From Westmoreland to Chae Myung-shin

Click to read in korean( 심각한 사건…최종조처를 통지해주시오)

On July 22, 1967, the commander of the Korean army, Chae Myung Shin attended and delivered a speech at the inaugural ceremony held at the White Horse Division in Ninhoa near Najang, central Vietnam. He always boasted that he developed the slogan "Protect one commoner even as long as you miss 100 Viet Congs," but he was not sure whether it was actually implemented as the slogan. Photograph of Korean Government Records

Lieutenant General Chae, Myung Shin

Commander

Republic of Korea Forces, Vietnam

605 Tran Hung Dao

Saigon, Vietnam

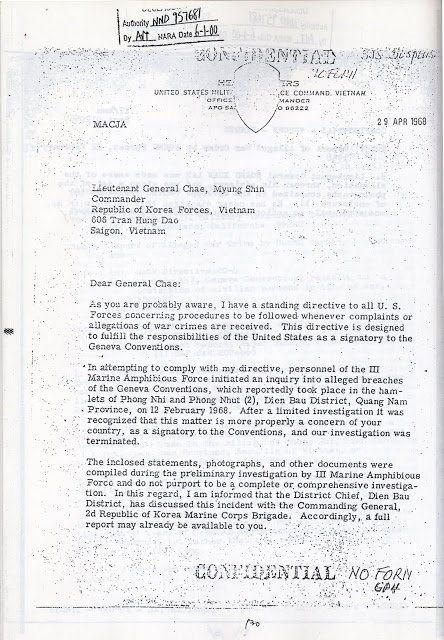

Dear General Chae : As you are probably aware, I have a standing directive to all U.S Forces concerning procedures to be followed whenever complaints or allegations of war crimes are received. This directive is designed to fulfill the responsibilities of the united states as a signatory to the Geneva conventions.

In attempting to comply with my directive, personnel of the III Marine Amphibious Force initiated an inquiry into alleged breaches of the Geneva Conventions, which reportedly took place in the hamlets of Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất(2), Dien Ban District, Quang Nam Province, on 12 February 1968. After a limited investigation it was recognized that this matter is more properly a concern of your country, as a signatory to the Conventions, and our investigation was terminated.

The inclosed statements, photographs, and other documents were compiled during the preliminary investigation by III Marine Amphibious Force and do not purport to be a complete or comprehensive investigation. In this regard, I am informed that the District Chief, Dien Bau Dien Ban District, has discussed this incident with the Commanding General, 2nd Republic of Korea Marine Corps Brigade. Accordingly, a full report may already be available to you

MACJA

Lieutenant General Chae, Myung Shin

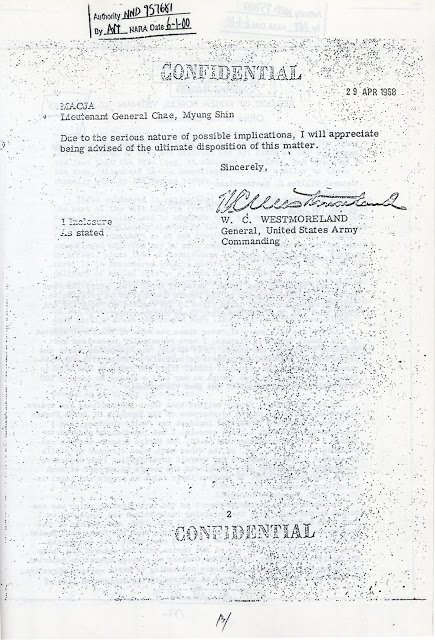

Due to the serious nature of possible implications, I will appreciate being advised of the ultimate disposition of this matter

Sincerely

W. C. WESTMORELAND

General, United States Army

Commanding

1 Inclosure

As Stated

Lieutenant General Chae Myung-shin, 42, commander of the South Korean military, read the letter while sitting at the commander's residence in Saigon. There was a handwritten signature at the end of the letter sent by the 54-year-old commander of the U.S. Army. The letter was brief and dry, inquiring how the South Korean military headquarters would act on the alleged atrocities of the 2nd Brigade of the Korean Marine Corps, which the U.S. military investigated.

Captain Westmoreland was 12 years older than Chae and had one more star than he did, but Chae wasn't concerned about age and rank. As commanders representing the U.S. and South Korean troops stationed in South Vietnam, their positions were essentially equal. Upon arriving in Saigon on October 20, 1965, three years ago, General Chae Myung-shin strongly advocated the exercise of independent operational command against U.S. military leaders who take for granted the South Korean military's subjugation to the U.S. military. To a military commander of a country, the issue of operational command was a crucial principle that could never be compromised.

Whenever he insisted on his own operational command, U.S. generals sarcastically criticized him, saying, "We raise, teach, and give all the money and supplies to the Korean military, but now their heads are so big that they won’t listen to the U.S. military." It was not entirely wrong of them to point that out, given that the U.S. military financially supported the Korean military in Vietnam, not to mention, paying allowances for officers and soldiers. General Chae Myung-shin nevertheless refused to budge, as he couldn’t shake off the belief that independent operational command of the South Korean military would have a profound impact on the honor and morale of the Korean military and the Korean people at large. He even tried advocating for autonomy to the U.S. generals directly at a meeting with key commanders, including Westmoreland, bringing up his turbulent battle experiences during the Korean War.

Some U.S. generals even looked moved by his powerful speech that only independent operational command of the South Korean military could block propaganda by the communist forces who belittle the fact that South Korea is dispatching mercenary soldiers as a contract of war, thereby eventually benefitting both countries. At the end of the speech, Commander Westmoreland grabbed Chae's right arm and raised it up as if he were a boxing referee announcing victory. A field commander, with sheer force, had broken through a wall that even President Park Chung-hee, who Westmoreland had met with prior to coming to Vietnam, had difficulty climbing over. So what then, was this letter? It detailed an incident that marred the dignity and honor of the Korean troops which Westmoreland had so respectfully acknowledged.

The letter was only one page, but the envelope was thick. A copy of the U.S. military's investigation report and a photograph of the incident on February 12, 1968 in Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất, Dien ban District, which was the operational area of the Second Brigade of the Marine Corps, were enclosed. The report contained statements from U.S. soldiers who witnessed the incident, the South Vietnamese militia and Vietnamese civilians. The photograph was of Vietnamese civilian victims, taken by a U.S. soldier after South Korean troops had left. Chae dropped his head. There were occasional requests from the U.S. or South Vietnamese sides to investigate unsavory incidents committed by South Korean soldiers. Chae, acting as jurisdictive officer, had even once given his final consent to the arrest and sentence officers and soldiers involved in the killing of civilians. The situation at hand was no different.

Chae Myung-shin was a cool-headed soldier. The United States in its anti-communist effort had sent some 300,000 ground troops and naval and air forces during the Korean War to save South Korea from the mire of communism. Chae certainly felt gratitude for their services, but that didn’t mean he had to agree with the strategy of Commander Westmoreland. Chae was also fundamentally cynical about the U.S. military's "Search & Destroy" operation in the Vietnam War, as he believed the method was unjustifiable. It would only cause collateral damage on countless victims, and the Viet Cong would most definitely reappear. With the Vietnam War involving irregular guerilla warfare in the jungle, where it was hard to distinguish between civilians and combatants, they had to reconsider a new way to respond to it.

Commander Chae Myung-shin coined the slogan just for the Korean military, “Protect one civilian, even at the expense of missing 100 Viet Congs.” It was an idea that focused more on the political rather than on the military aspect of the Vietnam War. This was taken from Mao Zedong (75) who successfully led the Chinese revolution. In October 1949, right before the Korean War, when Chae was in charge of the Battle of Taebaek in Yeongdeok, Cheongsong, and Bonghwa, North Gyeongsang Province as the commander of 2nd company of the 1st Battalion of the 25th Regiment, he pored over the book about Mao Zedong's guerrilla warfare, thinking that if he wanted to catch guerrillas, he would have to study their behavioral patterns. Mao Zedong was the supreme leader of the enemy state, who had driven Chang Kai-shek (81) of the People's Party to Taiwan, and founded the communist state in mainland China, but Mao was undoubtedly a respectable strategist. The books left a deep impression on Chae who was directing the partisan sweep-up operation near Mount Taebaek.

First of all, the "three major rules, eight major principles" that were established by Mao Zedong for the Long March of the Red Army were implemented in rural villages as a part of his operation. The "three major rules, eight major principles" entailed the following: "First, obey orders quickly. Second, they do not even receive a needle or a thread from the masses. Third, all spoils shall be used for the public. (three rules) Be polite in your words and actions and be fair in your dealings. Make sure you return what you borrow, and pay for any damages to civilian property. Do not trample on crops and do not resort to violence or swear. Do not engage in indecent acts with your wives, and do not abuse prisoners(eight principles).”

Mao Zedong said that "if guerrillas were fish, the people were water." Chae thought this was very well said. He too had to distinguish the fish out of the water, the Viet Cong from among the civilians, in Vietnam. This is how Chae’s slogan, “Protect one civilian, even at the expense of missing 100 Viet Congs” came to be. The slogan was also a sort of psychological warfare to win the trust of the civilians. They had to win over their hearts and make them allies in order to prevent the Viet Cong from taking root in the civilian population and therefore win the war. Chae stressed the service and protection of civilians to South Korean soldiers whenever he had the opportunity. He judged that as a result of his initiative, the number of civilian casualties caused by South Korean troops in the Vietnam War was markedly smaller than those caused by the South Vietnamese and U.S. troops. He could even swear this upon his honor as commander.

“Statement of Mr. Nguyen Xa, Vietnamese civilian, Popular Force soldier of Combines Action Platoon, Delta-2

At approximately 1000 on the 12th of February there were six of us sitting on top of the bunker in CAP D-2 watching the Korean troops.

A letter in English from U.S. Forces Korea, Westmoreland, to Korean Commander Chae Myung-shin, demanding to know the truth behind the incident of Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất.

Nguyen Xa

Doan Chi

Trinh Quang Ngcc

Le Binh

Nguyen Thi

Nguyen Huyen

When the attack began oh Phong Nhi it was so close to route #1 we could see what was happening without our binoculars. We only had one pair of binoculars with us.

The Korean proceeded to kill the villagers group by group, and we observed then at different places. At one places they shot 17 people at one time, another place 14 people, then another place 6 people and 3 people.

Later in the afternoon, after we patrolled through the hamlet, I found ten of my relatives killed and two were wounded (Nguyen Xang(14), and Nguyen Thi Thanh(9).

My friend’s family, PF Nguyen Thi, had 3 of his relatives killed and 1 wounded.”

Commander Chae Myung-shin grimaced. He was reading a line from the U.S. military investigation report enclosed in a letter sent by Commander Westmoreland. The statements made by U.S. military officers were pretty much consistent. If this report were true, the South Korean military had killed 100 innocent people under the pretext of catching a single Viet Cong, going directly against Commander Chae’s slogan. Far from separating the fish from the water, it was like changing the water to provide a more viable environment for the fish to thrive. The soldiers could have made mistakes. It’s not at all impossible to conceive that they lost their minds upon seeing their comrades dead and started shooting at the civilians. And then, they may have made a false report to the top. “Maybe this is a conspiracy,” Chae shook his head. The investigation report was written as if the South Korean military had systematically and intentionally massacred civilians. He looked at a picture of the bodies of Vietnamese civilians found in the village after the South Korean military's operation. It was hard to find any direct evidence or traces of the South Korean military's involvement in the incident. Maybe it was a plot by the Viet Cong to corner the Korean army.

After giving it a little more thought, Chae noticed that the letter and report signed by Commander Westmoreland seemed to lack weight. Westmoreland no longer had the same authority he once used to. He had already been relieved of his post by U.S. President Johnson on March 22, so he only had two more months remaining in his term. Johnson, who had been facing anti-war public opinion, both domestically and internationally, since the February 1968 Tet Offensive initiated by North Vietnam and the Viet Cong, suddenly named Westmoreland who was U.S. Army Commander in Vietnam as Army chief of staff. Creighton W. Abrams(54), who was deputy commander of the U.S. Army in Vietnam, was named as his successor.

It was in fact technically a promotion, but most U.S. media portrayed him as being reshuffled for misconduct. The commander was a symbol of pro war in Vietnam, even urging the U.S. Congress to remove restrictions on bombing North Vietnam, expand the war fronts to Laos and Cambodia, and increase the number of combat troops. The masses were extremely critical of him. As Commander Chae Myung-shin argued, the prevailing opinion was that the search and destroy operation was ineffective. Even during the Tet Offensive, Westmoreland was too optimistic about the situation and drew criticism for raising the damage to the U.S. military. It was also a huge disgrace that the U.S. Embassy in Saigon was briefly occupied by the Viet Cong. Johnson, who dismissed Westmoreland, gave up his presidential bid as a Democratic candidate on March 31, and made a shocking announcement calling for a halt to the bombing of the North, sending a gesture of peace to Hanoi. The dismissal of Commander Westmoreland, whose image was farthest from being peace-inclined, was but a prelude to all this.

Commander Westmoreland also fought in the Korean War in 1952. As commander of the 187th Fighter Wing, he has always boasted of his direct participation in airlift operations just before the armistice. Born in 1914 in South Carolina as the son of a textile mill manager, he was dispatched as a commander of an artillery battalion in the North African region and participated in World War II. Westmoreland was truly an elite soldier, being appointed Army chief in 1956 at the age of 42, the youngest age in U.S. Army history. He served as the Principal of the U.S. Military Academy, Westpoint since 1960, and succeeded as commander in the same year after being appointed as deputy commander under then U.S. Army Commander Paul Hawkins in 1964. Four years had passed since he became the commander-in-chief of the U.S. forces in Vietnam. The situation seemed strangely comedic, given that as he was leaving Vietnam being branded an incompetent expansionist, he sent a letter asking Chae to explain and take action on the South Korean military's atrocities.

Chae recalibrated. “The investigation report was full of errors. It'll be easy to deal with,” Chae thought as he prepared a reply. As the documents were sent by the supreme commander of the allied forces, who had a clear term of office, Chae had to provide an official explanation. He immediately ordered the headquarters of the 2nd Brigade of the Marine Corps stationed in Hoi An to investigate those involved in the incident.

*** For details on Chae's major activities and life, including the issue of operational command, refer to "Chae Myung-shin's Memoirs - Beyond the line of Death" (Maeil Kyungjae Newspaper, 1994) and "Chae Myung-shin's Memoirs - The Vietnam War and I" (Palbokwon, 2006).

- Written by humank (Journalist; Seoul, Korea)

- Translated and revised as necessary by April Kim (Tokyo, Japan)

The numbers in parentheses indicate the respective ages of the people at the time in 1968.

Read the last article

Chapter 23 : A day at the Central Intelligence Agency