E-Carceration is the use of technology to deprive people of their liberty. Electronic monitors combined with house arrest represent the most obvious and likely the most punitive form of E-Carceration. They are often seen as a progressive alternative to mass incarceration, but criminal justice advocates expressed reservations regarding these monitors and the private companies behind them.

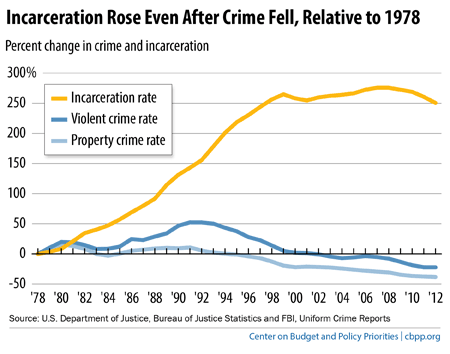

The United States has the largest known prison population in the world and incarcerates more people than any nation, including China [1]. Over the past half-century, the number of people behind bars in the United States jumped by more than 500%, to 2.2 million. Even as crime rates have dropped since the 1990s, the number of people locked up and the average length of their stay have increased. This paradox is often attributed to decades of “tough on crime” policies and harsh sentencing laws.

Furthermore, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the cost of keeping people in jails and prisons soared from $19 billion in 1980 to $87 billion in 2015.

In recent years, politicians on both sides of the aisle have joined criminal-justice reformers in recognizing mass incarceration as a fiscal sinkhole. Legislators have embraced ankle bracelets as a cost-effective alternative. As a result, the use of ankle monitors for pretrial defendants and convicted offenders rose nearly 140% from 2005 to 2015 [2].

Last year, President Trump signed the First Step Act, widely seen as a positive step toward criminal justice reform. However, this bill had the backing of private prison companies like GEO Group and CoreCivic, which happen to dominate the monitor market.

With its increasing use, monitoring threatens to become a form of technological mass incarceration, shifting the site and costs of imprisonment from state facilities to vulnerable communities. Parolees and people awaiting trial have to pay rates of $10-30 per day plus installation fees to private companies. And if they can't pay, they're sent back to jail.

One man who spoke to The Guardian [3] said he pays the private company that handles the GPS bracelet $840 per month, which makes it nearly impossible for him to get back on his feet. He is now homeless and sleeps in his car in Oakland.

Beyond the financial costs, ankle monitors introduce new ways for the wearer – disproportionately, people from impoverished and socially marginalized communities – to end up back in prison.

The minute you have a device on you, you can go back to prison because your bus is late, or the battery dies or there is a power outage.These new technologies are also contributing to mass surveillance, serving other purposes than individual control. Bracelet monitor, which use GPS, let companies surveil behavioral patterns. Some also have built-in microphones, which allow operators to listen in on conversations that wearers have with coworkers, family and friends.

Electronic monitoring is being used more widely by immigration authorities. In August, ICE raids led to hundreds of arrests – aided by GPS info from ankle monitoring bracelets placed on previously detained migrants. Oscar Chacón, co-founder and executive director of the Alianza Americas, a Latino immigrant advocacy group, said such a surveillance tactic “further stigmatizes” immigrants who wear ankle monitors.

Chacón said he believed the use of the worksite raids and of tracking ankle monitor data as a tactic was “part of a larger effort to use fear as a way of promoting the idea that people may feel so trapped” they abandon their immigration cases or leave the U.S.

The #ChallengingEcarceration project, part of the #NoDigitalPrisons campaign at MediaJustice, was launched in 2018 to contest the use of electronic monitoring in the criminal justice and immigration system. A set of guidelines was released to support advocates and policymakers to protect the human rights of those who are monitored. Over 50 racial justice, criminal justice and civil rights organizations endorsed the guidelines.

Instead of using technology to further restrain and punish people released from prison, authorities should be mobilizing technology to provide employment, education, training and other opportunities. People should be able to break out of this vicious circle that is the criminal justice system. This imperative is particularly crucial in the communities of color that have been hardest hit by mass criminalization and mass incarceration.

Links:

[1] Prison population rate, Study by World Prison Brief

[3] "Digital shackles: the unexpected cruelty of ankle monitors", The Guardian

Ted Talk, Bryan Stevenson, "We need to talk about an injustice" (2012)

Bryan Stevenson is the founder and executive director of the Equal Justice Initiative, fighting poverty and challenging racial discrimination in the criminal justice system.

Posted from my blog with SteemPress : http://blog.economie-numerique.net/2020/03/11/e-carceration-the-successor-to-mass-incarceration-and-surveillance/