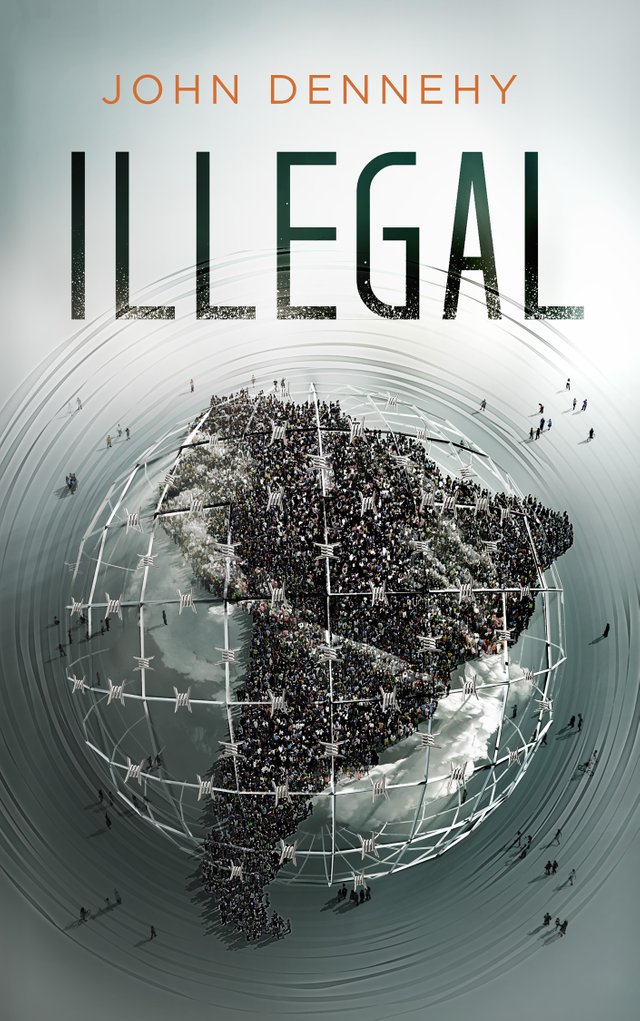

I'm a journalist for publications such as The Guardian, Vice, The Diplomat and Narratively and my first book, a memoir, came out just over a year ago [Amazon link]. It's won numerous awards and sold thousands of copies. And now I want to give it away. This is the seventh installment [Prologue | Ch 1 | Ch 2 | Ch 3 | Ch 4 | Ch 5] and every few days I'll give away another chapter/ section. From the back cover:

A raw account of a young American abroad grasping for meaning, this pulsating story of violent protests, illegal border crossings and loss of innocence raises questions about the futility of borders and the irresistible power of nationalism.

In Motion [Chapter Six]

I also traveled a lot. I had a growing wanderlust that the city of Latacunga could not satisfy. I rode my bike into nearby towns, took buses on long day trips, and every ninety days I crossed a border to renew my visa. In February, when my cross-border trip coincided with a break in classes I decided to make it a longer trip and see some of Colombia. “Just promise to write and call me,” Lucía told me, smiling. She had school projects to catch up on and wanted to spend more time with her son during the break, so the timing worked well for us.

For three weeks I traveled through Colombia. Much of that time was spent in a run-down port city on the Pacific coast called Buenaventura, where I learned firsthand about Colombia. Despite its location and dirty, industrial appearance, there was something I liked about the place.

The park near my hotel was only half a square block, had no trees and only a few large concrete boxes with dirt and plants. Benches were scattered around. It was basic and not all that pretty but it was still a public space where I could rest my legs and alternate between reading, writing and observing.

I was sitting there my second day in the city when a man approached me carrying a piece of plywood with holes cut out to hold and display about three dozen pairs of sunglasses.

“¡Gafas de sol! ¡Gafas de sol!—Sunglasses! Sunglasses! Would you like to buy some sunglasses?”

This question was directed at me, and I looked up just long enough to glance at him and say “No thank you.” He sat down next to me and told me how sunny Buenaventura was and how affordable his glasses could be, but I didn’t budge.

Then he changed the topic and asked in a casual tone, “Where are you from?”

“New York,” he repeated back to me. “Oh, it must be nice there. What are you doing around here then?” I looked at him for the first time. His skin was very dark, his stature short and his head was bald save for a few coarse white hairs that grew in a faint horseshoe pattern around the back of his sweaty skull.

“I teach English in Ecuador, but at the moment I’m on vacation. I just wanted to see Colombia, maybe go to a beach.”

“An English teacher?” His face brightened, revealing a single gold tooth. “I’m studying English at a school just two blocks from here. Do you want to go see the school? They would love to meet you there.”

“Sure,” I said, closing my notebook.

Five minutes after walking into the small school, I met the director. I told her I had to get back to Ecuador later in the month but she was happy to hire me on a day-to-day basis, for as long as I liked. I taught my first class that evening. I used the job to discuss Colombia with locals and spent my days learning about cocaine and free trade, politics and guerilla warfare—and I got paid for it. Buenaventura is extremely isolated, as the Pacific coast is almost entirely undeveloped and lawless—it was guerilla territory.

Despite Colombia’s natural beauty and friendly people, the nation was also host to tremendous violence. There were a variety of armed groups that controlled their separate fiefdoms, the general rule being whoever had the most guns won. This had been going on virtually without pause since 1948, but starting in the 1980s the cocaine trade began to heavily influence the fighting. The government and a myriad of rebel factions fought over control of territory and cocaine. War had, unfortunately, become part of life in Colombia as almost everyone alive there then had known no other time. Along with the government, the biggest player was a Marxist group, dating back to the time of Che Guevara, named FARC (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionario de Colombia / Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia), though there were often more than a half-dozen heavily armed groups operating at any one time. Another leftist guerilla movement, the Ejército de Liberación Nacional (ELN), had thousands of fighters. There were also numerous right-wing militias that had risen in response to the guerillas and often worked at the behest of large landowners. At the time, prospects for peace looked dim.

In 1984 FARC entered an indefinite cease-fire with the government and many members joined a new political party called Union Patriótica (UP) that was formed in 1985. The new party had many of the same demands, such as land redistribution, that the guerillas had been fighting for. The UP grew quickly and in the 1986 election had the greatest showing of any leftist party in Colombian history, electing several senators and congressmen. Unfortunately, this led to an uptick of violence against UP-elected officials and party members. In the following years thousands of members were murdered by right-wing militias, including the party’s leader and eight of its congressmen. In 1987, as violence spread among public figures, the ceasefire began to breakdown. After the UP presidential candidate was assassinated before the 1990 election, the party dropped out of the election and effectively collapsed.

In 2006 the fight, by then primarily between FARC and the government, was raging. It’s estimated that the guerilla force had 20,000 fighters and 3,000 hostages at the time. FARC was primarily based in rural areas and along Colombia’s borders. Unlike the much more developed and populated Caribbean coast, Colombia’s shoreline along the Pacific was sparsely populated.

Buenaventura was a government town in rebel territory and often a flashpoint between the two forces.

Sitting in the park my second week in the city, a man sat down next to me. “I’ve seen you here before. What are you doing in Buenaventura?” he asked.

“I like this park. I’m just traveling, but I’m also teaching English while I’m here,” I told him.

“You have to be careful,” he said. “There are many guerillas in this area, and some of them don’t like Americans.”

“I had heard that. But there aren’t any in the city, so I should be alright.”

He smiled at me. “We are everywhere. We just wear civilian clothes when we come into the city.” He stood and walked away before I could gather a response.

The conversation scared me a bit. I wasn’t sure if it was a threat, or just helpful advice.

The next day, I took a speedboat an hour north to a small fishing village only accessible by sea. Although it rained most of the time I was there, during one break in the clouds I wandered off and stumbled upon a desolate cove on a black sand beach. Smooth black rock formed a vertical semicircle of cliffs that isolated paradise. To one side, waves crashed violently against the wall while on the other they died out in the sand within a vast cave, where water dripped down from the ceiling into small pools, disappearing into the sand. Within the cove, water trickled down the cliff in a dozen tiny waterfalls, sometimes right off bright green plants that had managed to anchor themselves into the otherwise smooth black rock. It was one of the most spectacular places I had ever laid eyes on.

The following night when I returned to Buenaventura, I found a cheap hotel and went to sleep, unsure how safe it was for me to stay in the city any longer. I went out to breakfast in the morning and noticed machine guns on every corner, snipers on rooftops and the army behind makeshift bunkers in the middle of town. That made my decision easy; I left immediately. I later learned that shortly after my departure the guerillas attacked the town; their assault failed but both sides suffered heavy losses.

Lucía and I traded emails while I was in Colombia. Two days before my trip ended she wrote me that we needed to talk once I returned and told me she would be in Latacunga to meet me. I knew something was wrong as soon as I saw her. She was quiet and sad. I led her into my room and closed the door, sealing us inside together.

“I’m sorry. I’m so sorry, but . . . but . . . I got married this week.” Tears streaked down her face. We were sitting at the edge of my bed and she buried her head between my stomach and leg as I reflexively put my arm around her.

“What?! What are you talking about? You’re not married.”

“I’m so sorry, John, but I had to do it. Lenin [the father of her child] is an awful man and said he was going to take my child away. He said he would take away my baby if I didn’t marry him.”

I sat still, unable to move. She picked up her head, met my eyes with hers and said, “I love you.” She slowly and clearly enunciated every word and her voice hung in the air long after her head fell back down into my lap.

I felt no anger or sadness, at least not at first. More than anything else I was in shock. Lucía sobbed, her head resting on my thigh, but I just sat there, frozen, unthinking.

“He raped me,” she said without picking up her head.

My mind was beginning to function again but I didn’t speak or move. My Spanish was much improved from a few months earlier but there were still large gaps in comprehension. Did she really just say that? Am I understanding everything correctly? I finally managed to squeak out a single word. “¿Que?”

“I never wanted to be with him. He was much older than me and always found excuses to talk with me.”

“What?” I said again.

She sat up and turned her head slightly to look away from me and told me the long story; I didn’t interrupt her again. Some words were new to me but I clearly understood the general idea and in the months to come, as fragments of the story were repeated, all the details became vivid.

Lenin was in the military and stationed near her childhood home. He led her onto the base one day, took her inside an empty hanger and raped her. She was 17.

As she told her story, anger and sadness began to overtake my numbness: anger at Lenin; and sadness for Lucía.

“I was so ashamed. My inner thighs turned purple from the bruises but I couldn’t tell anyone—I’ve never told anyone until today. He kept coming over and bringing me gifts. He told me it was supposed to hurt the first time and since we had sex we were now obligated to at least date. So we dated for a few months and I had his baby, but I’ve always hated him.”

I cut her off. “So why did you marry him?!”

“He said he would take my child away and never tell me where he was or how he was. He said I would never see my child again. I told him I would never touch him and never sleep in the same room—but I can’t lose my baby.”

Her head had fallen back into my lap. Strands of her hair had stuck to her wet checks. I moved my hand to her head and gently brushed her hair back. And I stayed with her.

I wanted things to be simpler than they were. He was the villain and she the victim. In a strange way I felt closer and more dedicated to Lucía than ever before.

It wasn’t just about Lucía though. It was about me too. I desperately wanted to be good and looked for ways to confirm that I was doing right while burying any doubt. If necessary, I lied to myself and pretended everything was alright.

--

I'll be releasing the entire book this way but if you want to buy the paperback with Crypto-currency, email: [email protected] with your mailing address (U.S. only) and your preferred crypto and I'll respond with a wallet address and mail the book. $10 USD including shipping, limited time/ crypto only

And for anyone curious where we are in the story, here is the Table of Contents

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

This is a very interesting story, being from Venezuela i can asure you that you are going to have a lot of those stories for your next books or articles, it can be very shocking being an newyorker and live what its happening on the rural envioroment of South America. keep the good work and best regards.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

This a very awesome story even if It is a bit long.

What mattera more is at the end of evey bad abd harsh thing happens there ia always hope for the best to come.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

things human do for love....

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Hi @johndennehy!

Your post was upvoted by @steem-ua, new Steem dApp, using UserAuthority for algorithmic post curation!

Your UA account score is currently 1.664 which ranks you at #31673 across all Steem accounts.

Your rank has improved 585 places in the last three days (old rank 32258).

In our last Algorithmic Curation Round, consisting of 407 contributions, your post is ranked at #391.

Evaluation of your UA score:

Feel free to join our @steem-ua Discord server

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

gr8 story... you are a creative one

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Wow,what an interesting story,I must say,you are very creative.

I have upvoted and followed you,please kindly do that all my recents posts and follow me @amonolu,thanks

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit